Brinsworth House

IT IS known in the business as ‘the old pros’ paradise’ – appropriately enough, since most of its residents go directly from Brinsworth House to meet their Maker. Set back from a main road in Twickenham, Greater London, in an acre of carefully-tended grounds, the imposing mansion was the haven where elderly music hall performers went when they fell upon hard times. Others who fared better financially but needed full-time medical care found a refuge there, too. Many variety performers toured Britain, Europe and further afield with hardly a break for decades, staying in hotels, lodging houses and other ‘digs,’ and never had a permanent home to retire to.

I use the past tense not because Brinsworth is no longer functioning – it is, very successfully – but because almost all the performers who worked the halls and variety theatres are now long gone, and the net has necessarily been widened to include aged actors (Dame Thora Hird passed away there in 2003), television personalities and even geriatric radio DJs (Alan ‘Fluff’ Freeman was another resident).

Comedian Hylda Baker (“She knows y’know”) lived out her last days at Brinsworth in 1986 and cherubic Charlie Drake said “Goodbye, my darlings!” in 2006. Ben Warriss, straight man to Jimmy Jewel, was a resident, too, plus Serge Ganjou of the great adagio act The Ganjou Brothers and Juanita, Jack Wilson of Egyptian sand-dancers Wilson, Keppel and Betty, and countless others. Alf of Bob and Alf Pearson (“We bring you melodies from out of the sky, my brother and I”) celebrated his 100th birthday at Brinsworth House in 2010.

Opened in 1911, it was originally funded wholly by the profession from dues paid into The Music Hall Artistes’ Railway Association, which became The Variety Artistes’ Benevolent Fund, which turned into The Entertainment Artistes’ Benevolent Fund to open it out to all former workers in the performing arts.

For many years it has also been funded by the annual Royal Variety Performance and, since 2007 and with a wonderful sense of circularity, part-proceeds from phone-voting in ITV’s Britain’s Got Talent. It works like this: in exchange for the funding, the EABF arranges for the winner of Britain’s Got Talent to appear on the Royal Variety Performance, which is seen by 150 million viewers worldwide.

Bob and Alf Pearson from 1932.

When I visited Brinsworth in 1972, though, it was still rich in ancient music hall comics, jugglers, singers, acrobats and musicians, most of them chirpy and bright as they chatted away and tried to top each other’s gags and tall stories in the sunny lounge; a few immobile and staring into the past, as in any other old folks’ home.

Stan Stafford, The Silver-Voiced Navvy, entertains fellow residents. Picture courtesy Brinsworth House.Below: Stan in his prime.

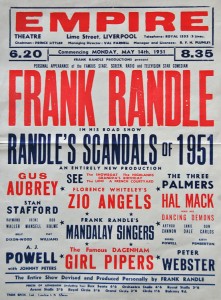

THE first to totter up to meet me on the arm of a smiling nurse was 76-year-old Stan Stafford, billed in variety as ‘The Silver-Voiced Navvy,’ who had been a mainstay of demented Lancashire comedian Frank Randle’s stock company in the 1940s and early 50s.

Randle (1901-1957), an alcoholic with serious mental health problems, was a subversive and uncontrollable talent greatly loved by Northern audiences even when he took his false teeth out and threw them into the stalls in a rage.

“I was with Frank for ten years,” said Stan. “He always liked to use me. He was a great artist, and offstage he was just like he was on, except when he went off the deep end. I did character parts in his sketches and so did Jimmy Clitheroe [4ft 3ins comedian – born 1921, died 1973 – who played a naughty schoolboy all his career], who was just starting.

“Randle was successful in London in spite of what people say. I played the Adelphi on The Strand with him – it only lasted two weeks and then the following week we went to a smaller theatre in another part of London and we had to have mounted police out on the Saturday night to keep the crowds back. The place was packed to suffocation.”

Stan capitalised on a freakish vocal attribute. “When I was ten years old I entered a competition at a fairground and won. I was a boy soprano. I went into the Navy and when I came out in 1920 I still had a soprano voice. I discovered at the age of thirty that I could also sing tenor and baritone. So I did my act in three voices. I started as a female impersonator on the halls. I was dressed beautifully and had all this make-up on, but somebody said ‘He’s got hands like a navvy,’ so that’s how the navvy character started. I used to sing soprano offstage before I came on and the audience expected a lady and I used to come on dressed as a navvy. That got a big laugh, and I used to say: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, before I was born my mother wanted a girl and my father wanted a boy, and I suppose they’ve both been satisfied.’

“I was born in Manchester, and I commenced on fairgrounds. To tell the truth, I started my real career singing in pubs in Manchester. I got seven-and-sixpence and three bitters, and sixpence if there was an encore. I was doing that for about twelve months and then I went into the music halls. I went to America and worked there for three months in 1932. We used to go into speakeasies and I met Legs Diamond in one of them. When I was asked to go to America I thought the man who booked me said the Palace, New York, but, in fact, he said the Palace, Newark, which is in New Jersey, where I had to play four shows a day and two on Sunday. Then I came home and worked on the halls in England with Billy Merson, Bransby Williams and Fred Barnes. My career has spanned sixty years. I still make occasional appearances now. I worked a few weeks ago in Rotherham in one of the clubs.”

Here’s Frank Randle in his famous Old Hiker sketch. Warning: this may be incomprehensible if you are unfamiliar with a Yorkshire dialect delivered by a man with no teeth.

NEXT up was a tiny, 86-year-old lady of great dignity and self-composure: Tina Elliott, who had been in one of music hall’s most lavish and stately acts. “I was with the Elliott Savonas,” she told me. “I married the youngest member of the act. There were four brothers, and I married Harry Elliott. After a while one of the sisters married out of the act and I took her place, and I worked with them for fifteen years. The Elliott Savonas were a very famous musical act, a saxophone band. We girls wore lovely white wigs. It was a very well-dressed show.

“Originally I started in the business when I was very young as a circus girl. I was about six years old. So I didn’t go on the music halls until I was married. I had a long career but I retired many years ago. In the Elliott Savonas there were seven of us, all on saxophones, playing the whole range of the instrument, from the largest down to the smallest. On the halls we were accompanied by the pit orchestra as well.

“When I first started, in the circus, I was a rider. It was a big switch from riding to playing the saxophone, but I must have been musical. When I joined the saxophone band it took me three months to learn to play. I was taught by other members of the act. It was a very wonderful show. We played the Coliseum, the Empire – all the big halls.

“I didn’t get to know so many of the big names of the music hall because the act was a headline act in itself, supported by other, smaller acts. It was a very happy family to be with – a very famous family. Everybody knew us. Coming from a circus, I never had a home until I retired. None of us did. We were in digs most of the time. I have a son, but he married out of the business, so the act is finished now. I’ve never touched a saxophone since I retired.”

MY next interviewee swiftly dispelled any air of (slightly forced) jollity that had been attendant on these little chats. Sad-faced little Sidney Bernard Mizuta, also known as Alan Kaye, was a 76-year-old retired juggler and acrobat, and the story he had to tell involved what was child abuse by any definition.

“My life,” he sighed. “Well, I’m afraid . . . my life, being a speciality act . . . you know what that is in show business, don’t you? Juggling or acrobatics. We call them dumb acts because we don’t open our mouths, you see. In my line of business we don’t do like comics or vocalists: go to pubs and join in this and join in that because we have to take care of ourselves. Our health, you see, is everything. We very seldom smoke, you see, because of our nerves.

“My story is almost a sordid one. In case I waste your time, is it worth telling you? Because it’s a sordid life, really, an acrobatic life. In the old days there were the speciality acts, the acrobats, the ‘risley’ acts – that is, spinning boys and girls on their feet; juggling them, so to speak while they lie down. Then there were the other jugglers, and the trapeze artists – what we called the dumb acts.

“I was born in London but started off performing in public when I was six years of age in America with a very famous circus – still going – the Five Ringling Brothers. I started when I was six until the last . . . let’s see; I’ve been working for a firm in London eight years; I’ve been here two years next August . . . and I was seventy-six last month – so I was a juggler for sixty years.

Jack Wilson of the fantastic dancing act Wilson Keppel and Betty also ended his days in contentment among fellow-pros at Brinsworth.

“In the old days, these acrobatic troupes, they were all very cruel, even to their own children, so they could learn the tricks quick, put them on the stage and make money out of them. They used to hit them and kick them and all sorts, even their own children.

“Now my father was an artist, a painter. Coming back from his studio one day he was run over and died about three days later. My mother was an actress, but not a big-time actress. I’ve got a marvellous memory. I can remember from the age of three, when I was sat up in bed with my father’s arms around me and that’s the last I heard of my father, you see, because he died. Mother had six children on her hands and in those days we didn’t get help from the Government. It was either work or workhouse in those days, so she gave us away – literally – gave us away to the owner of a Japanese troupe by the name of Ando.

“So there we were. We went with this man. We called him ‘father’ in Japanese because I am part-Japanese on my father’s side, you see. We were brought up with this troupe, about ten people, all Japanese, and then we went to America and I started climbing up a bamboo perch about 22ft high and my sister was on the other side of the pole. We called it the double perch, because one goes this way and one goes that way and there’s a socket at the bottom where you could put a single pole in and the boss would lift us up, us only being kids, you see.

“I was in America for about five or six years. I was with the Ando troupe in America about five years, then we came to England during the Russo-Japanese War. We were playing English dates – all music hall. There was no cinema. We played all round England and then perhaps we’d go abroad for two months. It could be Germany – the Winter Gardens, Berlin.

“I was with this troupe until about 1917. Then I broke away from them and joined another couple of Japanese in England and we went as a trio. I used to practice very hard because I wanted to be a single act. I used to get up at 5 o’clock in the morning, leave the digs and put in around five hours practice. I practiced, practiced, practiced until I was able to do a single and I then went by the name of Mitsuko and played England, Denmark, Holland and one or two other places.

“Then the Second World War came along and the Japs were against us so I couldn’t use a Japanese name or they’d shoot me. So I changed it to Alan Kaye. I was working in one of Moss’s theatres with Bernie Delfont, who was doing a walloping act – a dancing act – this is the business word for a dancing act, a pro’s word. So he was doing a walloping act with his brother Lew Grade. He was only a little feller, around my height. So I said to the brother, the little feller: ‘I’ll have to change my name.’ So he said: ‘Alan. It’s a lovely name, isn’t it?’ I said it is, isn’t it, but Alan what? And he eventually came up with Alan Kaye.

“Sometimes my wife assisted me. We played under the name of Alan Kaye and Gloria for quite a while. Soon the theatres began to close, one by one. I thought to myself that that this was no good. I had no other skill, so eight years prior to coming here I worked for a Jewish clothing firm – charming people – as a packer, folding ladies’ and children’s clothes.

“So when it comes to telling a story, like I’m telling you now, there’s nothing really to laugh about because it’s sordid. When I first started with a troupe a chap used to teach us. If we didn’t do it properly we used to get kicked in the shins, clouted in the face, and we daren’t speak to anybody, not even the landladies of the digs we used to stay in. If I was caught talking to anyone in the street – often a neighbour near the digs would stop me and say: ‘Aren’t you the little boy at the Empire?’

“But the boss of the act, he’d be scared in case I was asked whether I was happy. Therefore we were never allowed to talk to anybody. If we were seen speaking to anybody – crack! – right in the face. This isn’t widespread now, but in those days it was. The cruelty used to be wicked. Very bad.”

BILLIE Barclay, 76-year-old comedy performer, was a good deal cheerier. “I worked all the time in the music halls,” she told me. “A little concert party work sometimes, but mostly music hall. I had a partner, Jack Howard, and we were billed as Billie Barclay and Partner. I was a comedienne and we finished our act on the banjos, so it was a comedy-musical act. I was not born into the profession. I was a teacher, and I had to fight to get onto the stage. My mother said: ‘Over my dead body’ . . . you know the kind of thing. I was born in Weymouth. It’s a bit off the map, and that is why my mother didn’t like my going on the stage. But I finally got on and I liked every bit of it. I’ve no regrets.

“I started doing child impressions, then someone told me I was a comedienne. They could see the comedy, and after that, of course, I went from concert parties to the halls. My partner was the straight man and he fed me with lines. I used to do quick changes and then we’d finish on the banjos because he was a very good banjoist and I learned just enough on the banjo to accompany him.

“I used to work a la Nellie Wallace without the comedy make-up on, but I had comedy clothes I used to rip off and I would have an evening dress on underneath. But when I got to Australia they didn’t want that. It didn’t mean anything over there, you know. Not the comedy clothes. Even Nellie Wallace had to work in a soubrette dress. So I just worked in evening dress over there. Have you ever heard of Coram, the ventriloquist? He was top of the bill when we went to Australia and he said: ‘Get out all your old gags.’ They used to say our act was rather American; a bit like, say, George Burns and Gracie Allen. It was very common to have a funny woman and a straight man in the early days.

“I used to work a la Nellie Wallace without the comedy make-up on, but I had comedy clothes I used to rip off and I would have an evening dress on underneath. But when I got to Australia they didn’t want that. It didn’t mean anything over there, you know. Not the comedy clothes. Even Nellie Wallace had to work in a soubrette dress. So I just worked in evening dress over there. Have you ever heard of Coram, the ventriloquist? He was top of the bill when we went to Australia and he said: ‘Get out all your old gags.’ They used to say our act was rather American; a bit like, say, George Burns and Gracie Allen. It was very common to have a funny woman and a straight man in the early days.

“I spent a year in Australia and I was very glad to get back. They were very good to me over there but I was glad to be back after a year. That was in 1926 – such a long time ago. When I came back we always worked in music hall and variety, with an occasional revue. We appeared with a lot of the big people. Being funny always seemed to come easily to me. A man in Manchester used to write all our stuff. It wasn’t sophisticated cross-talk stuff, it was more in the music hall tradition. My partner would ask: ‘What do you do?’

“I’d answer: ‘I’m a dairy maid in a chocolate factory.’

“‘What?’

“‘I milk chocolates.’

“I’m miserable offstage. I think it’s generally true of people who were funny for a living. Our musical director used to say to people when we were in the pub: ‘Look at her. She makes people laugh. Look at her now.’ I’ve never been happy offstage. Never.

“People say music hall is completely dead. Not completely. Frankie Howerd, Ken Dodd – they are wonderful comics. But I don’t like the pops. Music hall is coming back in the clubs, isn’t it? It started that way. A lot of people think music hall and variety was like that television show The Good Old Days at the City Varieties in Leeds, with a chairman introducing the acts and banging a hammer. Perhaps it was briefly at one time but a lot of it, in my experience, seemed very refined, with very refined people – Daisy Dormer, Albert Whelan, that kind of act. Or Bransby Williams.”

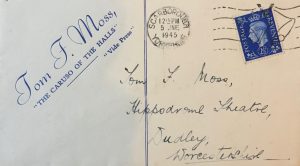

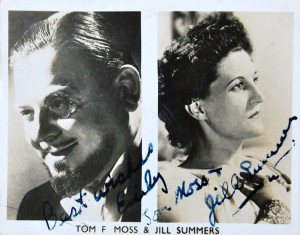

BRINSWORTH’S top of the bill for me was 72-year-old tenor and pioneer of cine-variety Tom F. Moss, who had been billed as ‘The Caruso of the Halls,’ a description he pinched from an earlier performer, Harry Fragson, conveniently murdered in 1913. He was also, I later discovered, the half-brother of John Major who in 1972 was already a Young Conservative and 18 years away from being Prime Minister of Great Britain.

Major’s father, music hall and circus performer Tom Major Ball, is thought to have fathered at least five children by four different women over a 42-year period. Tom Moss was his son by singer and dancer Mary Fuller, whose stage name was Marie Santoi. Mary Fuller also had a daughter who became the variety comedian and actor Jill Summers, born Honour Margaret Rosell Santoi Summers in 1910. Jill played blue-rinsed battleaxe Phyllis Pearce in Coronation Street for several years until she died in 1997. She and Moss sometimes appeared together on stage as a comedy double-act.

‘Tom F. Moss was indeed my half-brother, albeit forty years older than me,’ Sir John Major wrote to me, ‘and my family and I lived in his house in Brixton for some years in the 1950s.’ Sir John has amplified this comment in a brief section of his autobiography, and discussed further it in his book about music hall, My Old Man, including the moment when he realised that he and his middle-aged landlord shared the same father.

Tom was quite a character, refreshingly different to the rest of the placid old-timers at Brinsworth. He was a wheezing, snaggle-toothed old fellow with a drinker’s nose and gravelly Northern accent, happy in himself although he cheerfully conceded he had made some big mistakes. He blamed “booze and women” for the way his life had turned out but was scornful, unrepentant, humorous and defiant. I found him to be a very spirited and charismatic old party; he made me laugh and I liked him in spite of his tremendous air of seediness and the strong smell of drink off him.

He was looking for a publisher for his autobiography, and produced the dog-eared manuscript for my inspection. Foolishly, I was persuaded to take it away with me for appraisal, but when I got home I found it virtually unreadable: flowery, baffling and atrociously-written. An ever-present character throughout the rambling narrative was his penis, usually referred to in the third person as Rampant Caesar. The adventures of Rampant Caesar, who serviced – Tom’s word – a succession of blushing chorus girls and daughters of the gentry, each awestruck by RC’s outstanding qualities, quickly palled and I gave up half-way through, although I do remember one piece of advice solemnly offered by the author – engaging in cunnilingus must be avoided by professional singers at all costs because it rotted the vocal chords. These days we would say that Tom had ‘issues.’

When we spoke at Brinsworth, he remembered with great excitement the deal that had kept him and (until she keeled over and died while appearing at the Bradford Alhambra in 1924) his mother in drink throughout the 1920s. “We had an idea in 1919 for mother and me to provide accompaniment for a film entitled Father O’Flynn [a British melodrama directed by Tom Watts set in Killarney, Ireland, and involving a peasant accused when a tenant shoots the landlord who seduced his daughter]. The company that had it couldn’t sell it. They couldn’t get rid of it. It was nothing but scenery, more or less. Very little story in it. I saw the possibilities of putting a lot of Irish songs to the film and I suggested to my mother that we take the film. I said: ‘If they will take a rent, we’ll have it.’ But we had to put a figure down. I got my mother to sell her scenery and dresses. She was sure I’d ruined her but I said ‘I haven’t.’ She even pawned her jewelry.

“For about five months I thought I had ruined her. We were playing little picture houses and we had a job to get in. After a while, when we were playing a place called the Old Swan in Liverpool, that was a new picture house, and on a Friday night a chappie came up to me and said: ‘You Mr Moss?’ I said: ‘Yes.’ ‘Could I speak to you?’ I said: ‘Yes, come in our dressing room.’ He came in and he said ‘There’s my card: Sidney Carter.’ [Carter was an early British cinema mogul].

“Well, I didn’t know no Sidney Carter. I didn’t know the film business. He said he could offer me twelve weeks and asked me how much did I want. I thought: ‘I’ve had me leg pulled here, and I’ve had the tale told me, so I said: ‘Whoa, twelve weeks – cost you over £2,000.’ He told me he couldn’t pay me that money. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘I can give you ten weeks.’ I told him that would still be £2,000. ‘Still too much,’ he says. I told him that was my price. If he were bluffing me, I might as well bluff him. I let it go and he said he would wire me the next day.

“ ‘How is Miss Santoi?’ he asked and I told him she was fine; she’d gone out for a walk. Tell the truth, she were in the pub. Our rent for that week was £35 and then we had to pay for other things. So I’m asking £200 a week, as you can tell. When he’d gone I said to the manager, Frank Nolan his name was, I said: ‘I’ve had this chap to see me. Do you know him?’

“He looked at the card and he says: ‘Don’t tell bloody lies. Don’t lie! Sidney Carter, coming here?’

“I said: ‘What’s this? That’s his card, isn’t it? He brought his wife with him and he said that when we were in Scarborough he’d take us in his yacht.’

“He said: ‘Eh, don’t tell bloody lies, man. Do you know who Sidney Carter is? He’s the general manager of New Century Pictures. That man’s got a £60,000 mortgage on a theatre here and another £60,000 or £70,000 on the one across the road. It’s a millionaire you’re talking about.’

“I told him: ‘Well, he’s been here and I’ve asked him for £2,000 for ten weeks.’ He called me a bloody liar; he roasted me. Then my mother came in and I repeated it all to her. He said to her: ‘He’s a bloody liar, Marie. That man was never in here in his life. He’s a big man.’

“Anyway, I told him that he’d know in the morning anyway, after calling me a liar. I was very hurt about it. However, the next day we were in a very famous pub, the American Bar in Lime Street. Very famous pub, it was. And the phone rings, about midday. It’s from Frank Nolan, the manager of the cinema. He says: ‘Tom, I’ve got a telegram here. I’ve had the cheek to open it because I thought it might be important, and it is important. It’s from Sidney Carter. It says: Can offer you ten weeks, £1,750 best offer. Contact us Monday morning New Century Buildings, Leeds. Congratulations,’ he says, ‘and I apologise for what I said to you yesterday.’ I thanked him and he said: ‘Bloody good luck to you. I’ll buy you a bottle of champagne when you get over here.’

“I couldn’t believe it. It was incredible. I went there on that Monday morning with my mother. I leave my mother in a pub and I go and meet Sidney Carter and Sir William Durie and a bunch of old sirs and how’s-your-father. I didn’t realise who they were. I was an illiterate lad. I was only twenty then but I must have looked about twenty-six or twenty-seven. They asked me if I agreed to £1,750 for ten weeks. I thought: Well, I’ve played the game so I’d better keep it up. I said: ‘Well I don’t know if Miss Santoi will or not, but I’d better take responsibility and say yes.’

“ ‘Good fellow.’

“They brought me out a large whisky, a big cigar. They brought in a contract with seals and tapes and . . . I’ve never seen such a contact in my life since. I remember signing this and it would have been no good to them if they’d realised I was not twenty-one yet. I bluffed them in to it. And in those days, don’t forget, that was like about £3,000 a week today.

I’ve never seen such a contact in my life since. I remember signing this and it would have been no good to them if they’d realised I was not twenty-one yet. I bluffed them in to it. And in those days, don’t forget, that was like about £3,000 a week today.

“Well, I’m not kidding you – mother and son lived up to it. We had cars and a chauffeur with our names on his hat. Oh, we were buying new cars every five minutes! Buying my mother jewelry and this, that and the other. We lived like a royal party in our own way. Best of everything. Everybody chased us, once the news got round.

“I remember we went to see old Sam Jones of the City Varieties, Leeds, who was the manager there. He bought us champagne and he introduced us to others who were also buying us champagne. ‘Show us that contract,’ they’d say, ‘with all them seals and bloody whatnot.’ I was so proud. And we never looked back. But my mother died during that period – she killed herself with the booze. And I carried on by myself, still making all that money. Some weeks I’d make £400 or £500. A manager of a cinema would say ‘I can’t pay that,’ so I’d say: ‘Tell you what, I’ll take over your films what you’ve booked. I’ll pay for them but I shan’t show them unless we need to. I’ll rent the theatre.’

“ ‘You’re on,’ they’d say, because a lot of them were white elephants, these theatres; they didn’t do much business. But I did, because of publicity. They call them gimmicks these days, but in the old days they just said I was crackers. I had a jaunting car and two girls dressed up as Irish colleens. There were all these Irish songs with real live people singing them. It was a silent film and I put the words on the screen to synchronise with the actors. I was the fore-runner of talkies.

“When the real talkies came in my career went up and down. I went on the halls and into revue and had a great singing act. I was a tenor. I became famous . . . fairly famous . . . topping bills here and there, and even as late as 1949 I was getting £450 some weeks. Then I collapsed with a coronary thrombosis in 1951. It ended my career. I wasn’t even allowed to lace my own shoes for three months.

“But I’ve had a marvelous career. I’ve played the best theatres, topped the bill, made records. I’ve always been known as a legend in the business, some of the silly things I’ve done. I travelled a racehorse for two-and-a-half years and I used to make my stage entrance on this horse’s back. I’ve used doves in my act, snakes – even a fox. The things I’ve done used to cause a lot of excitement and publicity.

“I sang a lot of classical stuff, and I had the cheek to sing it in variety. I was not commercial enough, but I always sang my heart out. I sang the same kind of stuff that Josef Locke did, but we didn’t compete. He’d say himself that he couldn’t compete with me. He’d tell you that himself.

“Josef Locke . . . couldn’t compete with me. He’d tell you that himself.” Tom must have been pretty good to beat the great Irish tenor of the variety circuit. Here’s Locke in a clip from What A Carry On (1949, directed by John E. Blakeley). Note top comedy double-act Jimmy Jewel and Ben Warriss on the sofa.

“But I’ve no regrets. I was too much of a boozer, that was my trouble. I’ve been a naughty boy. Sometimes I begin to feel sorry for myself and I have to think to myself: why? I’ve had a good life. I’m still young at heart – I don’t feel old at all. Drink and women, that’s what did for me.”

And with that the half-brother of a future Prime Minister creakily stood up, farted, ostentatiously scratched Caesar (presumably no longer quite so Rampant) and shuffled off to Brinsworth’s well-stocked bar to regale a few of the other residents with tales of the glory days when he and his mother lived the high life and had champagne for breakfast and a chauffeur with their names on his hat.

And to close our visit to Brinsworth House, The Ganjou Brothers and Juanita, filmed in 1943.

All text Copyright Stephen Dixon 2013. All illustrations, except where specified, from Stephen Dixon Collection, acquired from various sources over a 40-year period and in many cases provided by the artists themselves in the 1970s. If anyone has copyright or permission issues, please contact me.

stephendee

| #

Doesn’t ring a bell with me, Stefan, tho it’s a very typical Sarony line. Anyone? Stephen

stefan Beard

| #

Just been reading the Leslie Sarony piece. Absolutely fantastic. Well done. A question if you don’t mind. Does anyone know the the title of the Leslie Sarony song that has the line “Oi ! how you gettin’ on? ” in it ?

ruskimic

| #

I do hope you can help me. I have been searching for many years for my Great Uncle Mr Albert Edward Rayner who went under the name of Dan Rayner. I believe he worked the Music Halls but I do know for sure he worked with Fred Karno. When Charlie Chaplin left Fred in America over a Pay dispute the American backers of the tour insisted that my Great Uncle Dan Rayner be called over from England to take Charlie Chaplin’s Place. It appears Dan was liked more at that time in America than Charlie was. Another man in the troupe at that time was Stan Laurel. When the show folded Dan was asked along with Stan to stay in America. As we know Stan stayed and found he fame and fortune. Dan however chose to return to England. He was last that I can find in a play Dick Wittington at the Empire Theatre advertised in the a local paper in Durham in 1948. Unfortunately I have not been able to find when or where he died. I am hoping that maybe on your search you came across some info on Dan Rayner. I live in Australia so am unable to search all the death records for England with out it costing me a fortune. So any help you maybe able to give me would be really appreciated. I know he went to America twice and once to Australia and also once to South Africa. I do know he was married to a lady named Barbara Robinson and they had a son Conrad Paul Rayner but I have been unable to find any thing out about these two members of his family. I do know they separated before 1935 and he lived with another lady named Phyliss but as to her last name I have no idea. I have been searching for nearly 10 yrs now and I don’t think there is any thing left on the net that can help me. You it would appear maybe my last chance. I will keep my fingers crossed that you did come across some info on him or you know some one that maybe able to help. He went to America in 1913 on the Lusitania and it shows at this time he is married. He then returns to America in 1914 on the ship Adriatic. I do believe he also did a radio show after 1935 for quite some time but do not know the name of that show. I do hope you can help in my search for my Great Uncle.

I also might add my great grandfather was Edwin Richard Barwick. He was also a Music Hall performer and appeared in the first Royal Command Performance. If you get the picture and Index to that even you will see him standing next to Pavlova. I would love to hear any information you may have found out about him. I do believe he was one of the first members of the charity named water rats, I know star was spelt back wards to get the rats part. Edwin did a lot of work for this charity in his day. What I would love to know is if there is any recording of Edwin Performing and if so how I would go about getting a copy or seeing any recording. I do have a photo copy of an old theatre bill with my grandfathers name boldly written on it. Again any help would be appreciated.

All the best and I look forward to hearing back from you in the near future

Kim Rayner

my email address is ruskimic@yahoo.com.au