Billy Russell

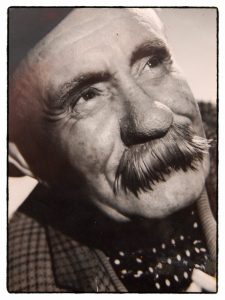

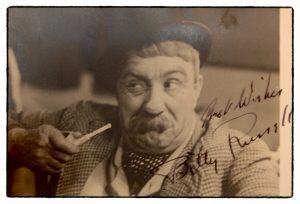

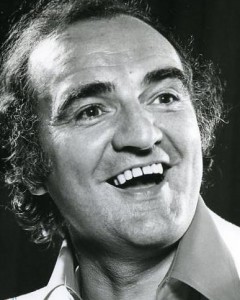

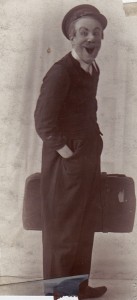

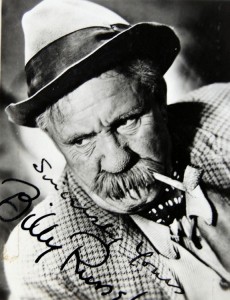

BILLY Russell had a blobby putty nose, pitted and warped like a golf ball left out in the rough for a few years. A walrus moustache covered his mouth and a good part of his chin. He dressed like a traditional workman from the 1920s, with a squashed and oil-grimed hat, hobnailed boots, collarless shirt with red handkerchief tied around the throat, moleskin trousers secured just below the knee with string. He would clear his throat and address the audience in a crackly Birmingham whine: “On behalf of the working classes . . .”

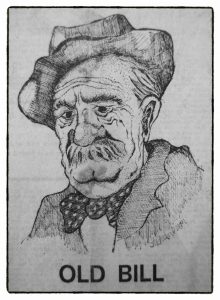

His real name was Adam George Brown, and, billed as ‘The Son of Toil,’ he was a star comedian during decades when a considerably downtrodden section of the community needed all the spokespeople they could get, even one who could only liberate through laughter. Born in 1893, he was a native of the Black Country, and throughout his long career was always received like the prodigal son in Birmingham and Wolverhampton. ‘On behalf of the working classes’ was the opening line in a laconic act he called Old Bill in Civvies, created just after the First World War.

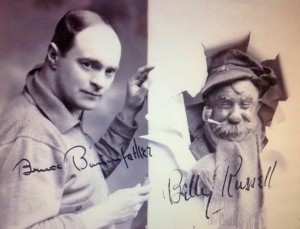

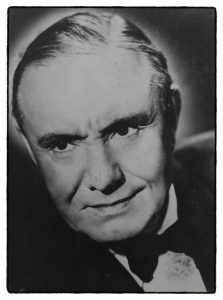

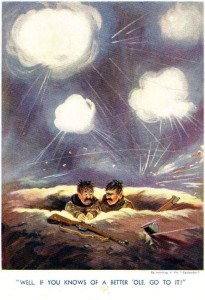

Cartoonist and serving officer Bruce Bairnsfather invented the stoical and phlegmatic old soldier in a famous series of wartime drawings. The best-known of these shows Old Bill and another soldier up to their knees in mud in a dug-out as bombs light up the sky and shrapnel rains down on them. “Well if you knows of a better ’ole,” says Old Bill, “go to it.”

Perhaps Russell appropriated and built on Bairnsfather’s creation because he was himself an accomplished visual artist, early in his career trying his luck on the halls as Baroni the Ambidextrous Cartoonist. His Old Bill in Civvies act struck a chord with the public and, while it involved carefully structured routines, Russell would often abandon the set act completely and stroll onstage with the evening newspaper and extemporise from the headlines. “He made cutting observations and comments on the current political situation,” said one observer. “This drew as many murmurs of approval and ripples of applause as it did laughs.”

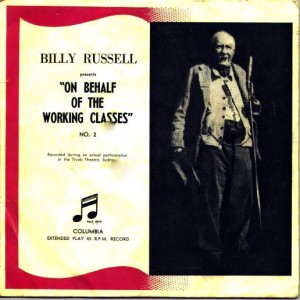

Here’s the song Billy began his act with when he was recorded live at the Tivoli Theatre, Sydney, during a tour of Australia and New Zealand in the 1950s.

Billy Dainty, the great eccentric dancer and comedian, worked with him once. “We were on a variety bill in Belfast and he arrived at the theatre off the ferry ten minutes before he was due on,” Billy told me in the 1970s. “He just had time to do his make-up and tie the string round his trousers and he was on. As he walked out of the wings, a bloke in the audience shouted: ‘Piss off!’ ‘All right,’ said Bill, very unconcernedly, strolled slowly off, undid the string from round his trousers, and was on the next ferry home. That was Old Bill.”

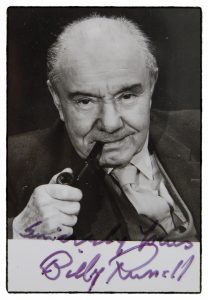

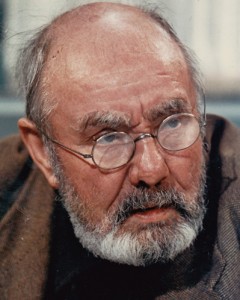

At 79, Billy Russell had outlived the act and the theatres where he had toured it for forty years. He appeared in Old Time Music Hall shows from time to time, along with most of the others in Voices of Variety, speaking, as ever, ‘on behalf of the working classes,’ but being an astute and adaptable man, he had forged a new career in the winter of his life as a film, stage and television actor, enlivening many one-off dramas, crime shows and soaps, being particularly remembered as Adam Lambsbreath in a BBC version of Cold Comfort Farm in 1969. He was a formidable and feared scene-stealer, and performers groomed by television stood little chance against the old man who had been quelling hecklers at the Glasgow Empire and the Argyle, Birkenhead, since before they were born. The meticulous attention to detail in his variety act carried through to everything else; on the opening night of David Storey’s The Contractor at The Royal Court in 1969, about a gang of marquee-erectors, he went round the dressing-rooms and rubbed dirt under the fingernails of all the actors “for authenticity.”

Billy Russell lived in a charming, airy, wood-panelled house at Reading; at the bottom of the garden was the river where his friend Max Miller once moored his cruiser. I had seen Russell plenty of times on television and there he gave the impression of being a large and robust old man, so the tiny, frail figure who opened the door to me came as a surprise. He shuffled along the hall towards his study in carpet slippers, and I noticed that the backs of his hands, and his bald head, were mottled and freckled like a toad’s stomach. He had several days’ growth of scrubby white beard – grown, he explained, for a film part.

At first his attitude was challenging and slightly hostile as he weighed me up with disconcerting intensity. But after a while, in that sunny study, walled with his own paintings and old variety bills and certificates testifying to his appearances in Royal Variety shows, he relaxed and opened up, the steady ticking of the grandfather clock pacing him as he ruminated about a career that had begun in the first year of the twentieth century.

‘PEOPLE often say to me that music hall and variety will never come back. ‘What do you mean?’ I always answer. ‘You can’t kill something that has existed for over 3,000 years.’ The oldest form of entertainment is the one I specialise in – the storyteller. Before people could read or write, there was always the storyteller. Three thousand years ago in the marketplaces of China and the Far East there were acts that are still being presented today. A different presentation, perhaps, but they are still those self-same acts.

“Acrobats, doing the same tricks. Conjurers, using the same principles of magic, of which there are only about seven. And the storyteller. If you go to Marrakesh in Morocco you will find a show that goes on right round the clock. They come from all over Africa to perform there. What is done nowadays is merely a new presentation of an old art.

“I first appeared on the stage in a melodrama at the Theatre Royal, Gloucester, in 1900. I was seven years old. My mother died that year and my schooling finished. I only had three years’ formal education, that’s all. I often appeared whenever a child actor was wanted, and I learned from the great music hall artists. People like Bransby Williams, who later became a very good friend of mine. George Robey. These people taught me projection and clarity of diction, which was important, because, of course, there were no microphones in those days. The audience had to hear you at the back of the gallery, and if they didn’t, then you’d soon hear them!

“I learned a marvellous lesson when I was young, working in fairgrounds. There was a tent that used to get more laughs than anything else. People would roar, and what they were laughing at was themselves, through a distorting mirror. A fellow called Roberts bought a set of these distorting mirrors and it was a bloody good investment. He had to provide nothing, just the mirrors, and people would walk around and scream with laughter. And that’s what I’ve spent my life doing. Holding a mirror up to people.

“Before the First World War you could work around Manchester, say, for over six months. As a matter of fact, I did it. I’d finish in pantomime in Manchester and then stay near the city – this was before I got to the top, of course – working the small halls. Bury, Radcliffe, Farnworth, places like that. Round the Broadhead theatres. By the time I’d finished the rounds, it would be time to rehearse for pantomime again, and I hadn’t shifted from Manchester. And the next year: Newcastle, the same thing. Then round Birmingham. Then South Wales.

“That was my career in those days. I never saw ten quid a week. A fiver was as much as I ever saw. It’s a funny thing – I paid that much just yesterday for a load of manure for the garden. But I look back on those days with a good deal of affection because I was learning. It was a good school.

“About a fortnight ago one of the TV directors rang me up and said: ‘Bill, I’m in a bit of trouble. I’m doing a thing called The Pigeon Fancier and I’m an old man short.’ Ironically, I could have had the lead in that earlier, but I wasn’t well. He said: ‘I’ll pick you up today,’ so he came round and we went off to Nottingham. I asked him exactly where we were filming and he said: ‘Eastwood.’ I said: ‘Oh my God! That’s where D.H.Lawrence was born and it’s the first place I ever did a solo turn, over sixty years ago. The Empire, Eastwood. I earned fifty bob. It’s a Woolworth’s now.

“Comics today are not funny in themselves. They rely on writers. I write my own songs and I write my own jokes. I didn’t create the Old Bill character myself, of course. Bruce Bairnsfather, the cartoonist, created him. But I brought him to life on the stage. I was a bit stuck. I came back from the First World War, where I’d served with the South Staffs Regiment, and I was doing a ‘trench philosopher’ act. My father had a couple of theatres in Hertfordshire and I was working for him. The fellow who was doing bookings for him, Frank Lowery, came up from London and saw my act and he said: ‘Yes, very good, but people don’t want to know about the war. They want to forget it.’

“So, okay, I dropped it. I threw it away, and I started working in the scenic studios, throwing the paint on. I got an offer to go in a tatty little revue in Birmingham and when I was on the top of a tram one day I saw a bunch of fellows working on the line, a bunch of navvies. One of them looked up and, by God, it was Old Bill! I thought: ‘That’s it – Old Bill in civvies!’ And so ‘On Behalf of the Working Classes’ was born.

“Of course, even I could see that there wasn’t much to laugh at in the 1914 war, but Bairnsfather managed to see a bit of humour in it, and so did I. When I first brought Old Bill in Civvies to the public in 1919, I had to age myself. I gradually did away with most of the makeup as the years went on. I just kept the bulbous nose and the walrus moustache.

“In those days the audiences were not tolerant. If they didn’t like you, they would let you know it. Jeering, catcalls – you couldn’t be heard. You’d be drowned out. I played North Shields once and there was an act on the bill who was excellent, but the audience just didn’t want to know. They didn’t understand it and that was enough. He had a damned good act, this man, but his mistake was that he was doing impersonations of people they had never seen; stars who never got up there. Wilkie Bard, Gus Elen, people like that. It was no good doing impersonations when people couldn’t compare them with the originals. You have to know your audience.

‘ANYTHING that is easily got is not worth having. The comedian had to put in a long apprenticeship. Often he’s forty before he’s really well-known. I know, through experience. Even today, when I see myself on television, I think: ‘Oh my God.’ With seventy years experience on the stage behind me, I’m still learning.

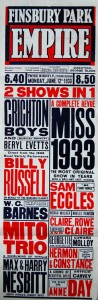

“I learned the hard way. A season at Blackpool. You learned there because every house was different. When you don’t go down well, you can’t blame the audience. You can’t blame them if they don’t like what you are selling. You have to sell them something that they do like. I’ve done three Royal Variety Command performances – 1933, 1947 and 1954. But there’s no competition today. My God! A lot of the comedians today seem to aim at the mentality of a five-year-old. I’d say: Put on a Punch and Judy show; it’d be a bloody sight more entertaining and adult.

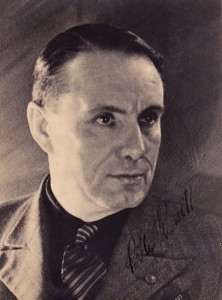

Bruce Bairnsfather poses with Billy, here made-up to look exactly like his ‘Old Bill’ creation. Picture courtesy Carol Pearson, Billy’s great-niece.

“Too many artists today will settle on something and they will say: ‘Well, this is it. This will do.’ If you keep a shop, you have to keep the shelves replenished, and that’s what I have always endeavoured to do. I think complacency is very bad for anybody, and if you are an artist and you start to think that you are good enough – well, that’s the end of the road. You never are good enough. That’s been half the fun of it for me because I always like to solve problems and accept challenges.

“Not long ago I was in a late-night TV show. A young comic went on and he started up with bloody awful dirty gags. Not one clean gag. Andrew Faulds, who was in the chair, turned to me and said: ‘Now we’ll ask a veteran. Billy Russell, has humour changed much since your day?’

“I said: ‘Don’t mention it in the same breath! It’s not in the same street. What we just heard wasn’t humour. It belongs in the tap room or the barrack room, not in a place of public entertainment. You just wouldn’t be allowed to say that sort of thing in the old days.’ He said: ‘Oh, come on, Bill. What about Marie Lloyd and . . .?’

“ ‘Just a minute,’ I said. ‘You’re not old enough to remember Marie Lloyd, so whatever you are going to say is hearsay evidence. Marie Lloyd would not have been able to say half the things that are ascribed to her.’

“They say that Max Miller said such-and-such a thing. He most certainly did not! He wouldn’t be allowed to! Suggestion, yes. Innuendo, yes. Obscenity, no. Robey, for instance, would tell stories that would throw the onus on the audience. ‘I was in a hotel in Brighton,’ he would say, ‘and in walked a lovely young couple. They were so shy, and they went up to the desk and signed in and the clerk said: “Here’s the key to your room, Mr and Mrs . . . er, Smith.”’ And the audience would laugh. Robey would look at them loftily and say: ‘As a matter of fact, that was their name.’

“I can quote by heart the Variety Artists’ Federation arbitrators’ award contract, which is a four-page document. When I first started on the stage, girls were not allowed to show their bare knees. The Brewster Sessions would object to a hall’s licence, and no hall dare risk that. They would have been closed down.

“One Monday morning I arrived at the Hippodrome, Birmingham, and the manager said: ‘For God’s sake, Bill, be careful with your material.’

“ ‘Why, what’s the matter?’

“He told me that a famous artist had been ‘done’ that week – for pretending to smack his wife’s bottom on stage. You couldn’t say ‘damn’ or ‘hell’. You weren’t allowed to refer to homosexuals or effeminacy. You would be barred. People nowadays are shocked by dirty jokes. They marvel that a comic has the audacity to say these things. But is it humour? When you break it down, there’s no humour in sex. There’s nothing funny about it. When you are doing it, it seems like the most serious thing in the world, so any humour in it must result from inadequacy.

‘MY stories were always inoffensive. I told stories about ‘the wife’. I used to say she was too big to get in the bath. Well, she could get in, but there was no room for the water. We have to take her out into the backyard of a Friday and swill her down with the hosepipe. When it’s a bit cold, we can’t manage that so I go over her a few times with the Hoover. That sort of humour. Inoffensive.

“Or I’m working down the garden and the wife shouts: ‘Here’s your dinner.’ I says: ‘What is it?’ She says: ‘Steak and onions.’ I says: ‘Blimey, you’re kidding me!’ and the wife says: ‘I’m not kidding you, I’m kidding the neighbours’.”

Some things never change, I thought to myself as I listened to Billy’s next comments. I knew a few young comedians back in 1971, and I’ve known plenty since, and a constant complaint is the cardinal crime of joke-stealing. In the great days of the halls you could tour the same act for decades, but a routine purloined and used by the thief on television can kill it for its originator. This was obviously something that still rankled with Billy.

“In TV Times the other week there was a gag I coined about Manchester: ‘You awake in the morning to the sound of the birds coughing.’ I threw it away years ago but there it was in TV Times. A well-known comedian is currently cracking it. Another famous young TV comic has used all the records I’ve made, every side . . . ‘our street is so rough that if anyone pays the rent a copper comes round to see where they got the money. The walls are so thin that you can’t keep yourself to yourself. Every time you put a shovel of coal on the fire you’re cooking someone else’s dinner. Every time they pull the chain next door, they empty our bath’.”

Billy Russell was not a prolific recording artist, but the two live shows he recorded in the late 1930s, in London and Birkenhead, are superbly evocative examples of what it must have been like to be in a variety theatre, and have been included in several music hall compilations of more recent years. He also recorded ‘On Behalf of the Working Classes’ in Australia when he was touring there in the 1950s. “As far as my gramophone records are concerned, I made an arrangement at the Grand, Clapham. I took the date, even though the fellow couldn’t pay my salary. He was a pal of mine and he said: ‘I can’t pay you the kind of money you are asking, Bill.’

“Now Gracie Fields had made a record at the Holborn Empire, and so had Max Miller, and Regal Zonophone had approached me and asked me to do the same. So I told the chap at Clapham that I would play the date for him at the reduced money, but that on the Friday Regal Zonophone were to record my act. I fixed it up and I agreed with the orchestra that I’d pay them so much, and I made all the arrangements.

An extract from On Behalf of the Working Classes, recorded at the Argyle Theatre, Birkenhead, in 1939. Warning: Billy was a comedian very much of his time, and the humour here is extremely sexist and, I think, rather mean-spirited.

“Well, after we’d done the recording, the musicians stepped in. They didn’t want outright payment, they said, they wanted a percentage of the royalties. They went back on their word, in fact. So I said: ‘All right, we’ll wipe it. Wipe ’em off. We’ll do the whole thing again and I’ll re-record the song in a studio.’ We got a whole load of giggers, and I suggested that, so the original musicians couldn’t claim it was them, we’d put a piano-accordion in the band to make it sound completely different. After all, it was my material. I’d written it, so why should the bloody orchestra get some of the royalties? They had to play the theatre that night in any case, and were being paid, and it was reneging on the original agreement.

“So I went off to do it in the studio and, you know, I just couldn’t get into the character. So my wife said to me: ‘Put your Old Bill makeup on.’ And she was right. That was it. Only just the same material, but I got into my stage togs and put the makeup on and it worked.”

Billy got quite worked-up during his diatribe about his problems with the musicians, thumping the arm of his chair and gasping for breath, and I realised how stubborn he must have been, how protective of his rights and earnings. He mustn’t have been the easiest person to work with. When his rage had subsided, he closed his eyes and was silent for a while and I thought he’d nodded off or, for an alarming second or two, died. Then he chuckled throatily and resumed his story.

‘I USED to get most of my material in pub tap rooms,” he said. “I would go into a town when I was on tour and just listen to people’s conversation. Nobody knew me because my character and appearance on and offstage were completely different. I’d listen to people and then I’d twist it a bit. For instance, a fellow I knew by sight used to go into a pub in London, the Crown. And his nose! Well, you’ve never seen anything like it in your life. It seemed to get bigger and bigger every time I saw it, and it had sprouts on it. And it set off a train of thought in me about noses. I did a whole routine about this nose, although on stage I said it was about one of the wife’s relations:

“I went out with him one night and he got so drunk that I couldn’t see him. We was staggering ’ome and he fell flat on his face on the road and his nose got stuck in the tramlines. I tugged and tugged but I couldn’t get him out. He’d be there now if I hadn’t had the presence of mind to pick him up by the ankles and push him along to the depot. I shall never forget the day he died. They couldn’t get the lid on the coffin because of his nose. It wobbled. So they bored a hole in the coffin lid, but his nose stuck through and it looked unsightly. So the undertaker sent for his carpenter and he planed it down. With a coat of varnish, it looked like a knot in the wood.

“Another story that was a favourite of mine was the Regent Canal story. I was boozing with this fellow during the blackout, I would say, and after chucking-out time we found we’d missed the last bus ’ome, so we decides to walk along the canal bank as a short cut. All of a sudden – splash! – he’s gorn. So I walks on a bit and when I was at Park Road I sees a copper and I says: ‘Hold on a bit, my mate’s just fallen in the water back there.’

“The copper says: ‘Do you know exactly where?’ and I says: ‘No.’ ‘Well,’ he says, ‘it’s no good looking for him in the blackout. We’d better go to the fire station and get the fire engine out. It’s got a searchlight on the top.’ Anyway, we finds him floating in the water, held up by the air in his raincoat. The copper gets a long pole with a hook on the end, drags him to the bank and begins artificial perspiration. Didn’t ’ave no effect.

“Well, the copper puts his hand accidentally on my mate’s stomach and a lot of water comes out of his mouth and nostrils. The copper says: ‘This water wants to come out. Just nip down the ’orspital and get a stomach pump.’ Well, I was a bit hard of hearing and I comes back with a stirrup pump. The copper says: ‘Well, that’s not what we wanted, but we’ll have to make do. Bung the tube down his throttle, and I’ll do the pumping.’

“And that’s what he done. He starts pumping, and out comes fag ends, matchsticks, orange peel and gallons and gallons of water. A bit of a crowd starts to gather, as they will on these occasions. The crowd gets bigger and bigger and more and more water comes out of my mate’s mouth. After a bit the copper says: ‘Blimey, this is going to take hours.’ And a bloke in the crowd says: ‘It’s going to take weeks if you don’t lift his backside out of the water!’

“That was the kind of stuff I did. But my favourite comedian – a real comedian’s comedian, was Gillie Potter, the most academic of our comics. He did all right on the radio, but he never seemed to go down very well in the theatre. I remember one time when he didn’t get a single laugh, except for one man who responded to every gag. About halfway through his act, Gillie instructed the man working the spotlight to shine it on this bloke. ‘My dear sir,’ said Gillie, ‘would you kindly do me a favour? Arise, and let the rest of the audience see you. Otherwise, they might think you were some kind of contraption I work with my foot.”

“Brilliant! He used to open his act: ‘Last evening at approximately twenty minutes after high tide at Runcorn . . . I am talking purely to the intelligentsia, of course’ – he would look down at the stalls when he said this. ‘Those people up there in the gallery have their own form of amusement. They rarely come down. Last Friday I believe they had fried fish and folk dancing. They stay up there for months. Occasionally someone comes down to buy a pram.’

“Brilliant stuff, but it went right over their heads in those days. ‘It is customary on these occasions to offer a little vocalisation,’ he would say, ‘but I fear the symphonic layabouts of the pit orchestra are conspicuous by their absence. Has someone been giving them money? I don’t blame them. People feel sorry for them. If you have any morsels of unwanted food, by all means sprinkle them along the rails and perhaps manicured digits will arise to grasp them, but if you give them money you see what transpires – they then dash from their perfumed tents.’

“Onstage he wore an Harrovian straw hat, Oxford bags [loose trousers], and he always carried an umbrella. A brilliant man. Never got anywhere, really, except as a radio comedian. I think he was more brilliant than James Thurber. I was going to say that he was an English Thurber, but I personally think he was more brilliant than Thurber. I think he was the greatest English humorist of the twentieth century. But – unsaleable. Too brilliant. He was booked into the London Palladium on the same bill as Danny Kaye, when Kaye was at the height of his fame. On that night the place was full of bobbysoxers – kids, you know – and as Gillie walked on he quietly said: ‘I can’t handle this hysteria. Kindly collect my music, and I bid you a fond farewell.’ And he left the stage. He never came back.”

‘I TELL these ‘mocky’ comics, these young ones who come along, to do what I did. I learned from the masters, those at the top of the tree. Learn from the present-day masters. Did you ever hear Bob Hope crack a blue gag? Did you ever hear Jack Benny crack a blue gag? You see, it’s there for them to see. I saw it. I saw the secret of it. It was this: don’t be clever. You be the frustrated party; you’ll get the laughs. People laugh at frustration.

“Formby, who wasn’t a comedian by any means, was always the simple one. Sandy Powell was the same – ‘Can you hear me, mother?’ All of them. Chaplin, frustrated. Hancock, frustrated. The wise guys are in the minority. The audience certainly admires their skill, but I don’t think they love them in the same way.

“Max Miller wouldn’t go above Birmingham, you know. And he couldn’t get his act over in garrison towns. Oh blimey – I played with Miller at Portsmouth and he died the death of a dog. He was here a fortnight before he died. He used to have his boat tied up at the back here and he’d often bob down to my house to see me. But Max used to pick his grounds. He wouldn’t go North.

“The material I see nowadays I could write without thinking. I heard one the other day about a men’s hairdresser in the West End. He’s not got male hairdressers, he’s got women. Topless! You can imagine one of those standing in front of you: ‘Now, sir, how would you like it?’ I could write that kind of stuff. There’s nothing clever in it. It’s dead easy. But, you see, there are no holds barred today. Unshackled.

“If there were still the halls and theatres I’d quite happily go back to being a touring comic, even at my age. I won’t work the clubs because all they want is muck, and I won’t prostitute what talent I possess. When I’m not acting I keep busy with my painting and my gardening.

“Funny thing. Not long ago I was in Yorkshire recording an episode for a television series. I was the guest star. And after I’d finished doing my acting the producer – a young chap – came over to me and the subject got on to comedy. He looked at me and he said: ‘I believe you used to be a bit of a comedian, Bill’.”

Work’s done, Billy . . .

ON November 25th, 1971, just a few weeks after we met, Billy Russell was at the BBC studios in London, rehearsing a new play. He was sitting off-camera, supposedly studying his lines, and when his cue came, the old pro failed to respond. Thinking he was asleep, a production assistant gently shook his shoulder, but Billy had taken his final curtain.

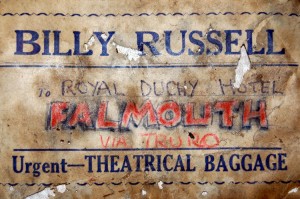

While researching this site, I wrote to the address in Reading where I talked to Billy in 1971 and asked if anyone from the family still lived there. No, replied the present owner, the name Billy Russell meant nothing to him – except for this scrap of paper, uncovered beneath the floorboards by workmen carrying out renovations.

All text Copyright Stephen Dixon 2013. A shorter version of this story appeared in The Guardian newspaper in the 1970s. All illustrations, except where specified, from Stephen Dixon Collection, acquired from various sources over a 40-year period and in many cases provided by the artists themselves in the 1970s. If anyone has copyright or permission issues, please contact me.

stephendee

| #

Doesn’t ring a bell with me, Stefan, tho it’s a very typical Sarony line. Anyone? Stephen

stefan Beard

| #

Just been reading the Leslie Sarony piece. Absolutely fantastic. Well done. A question if you don’t mind. Does anyone know the the title of the Leslie Sarony song that has the line “Oi ! how you gettin’ on? ” in it ?

ruskimic

| #

I do hope you can help me. I have been searching for many years for my Great Uncle Mr Albert Edward Rayner who went under the name of Dan Rayner. I believe he worked the Music Halls but I do know for sure he worked with Fred Karno. When Charlie Chaplin left Fred in America over a Pay dispute the American backers of the tour insisted that my Great Uncle Dan Rayner be called over from England to take Charlie Chaplin’s Place. It appears Dan was liked more at that time in America than Charlie was. Another man in the troupe at that time was Stan Laurel. When the show folded Dan was asked along with Stan to stay in America. As we know Stan stayed and found he fame and fortune. Dan however chose to return to England. He was last that I can find in a play Dick Wittington at the Empire Theatre advertised in the a local paper in Durham in 1948. Unfortunately I have not been able to find when or where he died. I am hoping that maybe on your search you came across some info on Dan Rayner. I live in Australia so am unable to search all the death records for England with out it costing me a fortune. So any help you maybe able to give me would be really appreciated. I know he went to America twice and once to Australia and also once to South Africa. I do know he was married to a lady named Barbara Robinson and they had a son Conrad Paul Rayner but I have been unable to find any thing out about these two members of his family. I do know they separated before 1935 and he lived with another lady named Phyliss but as to her last name I have no idea. I have been searching for nearly 10 yrs now and I don’t think there is any thing left on the net that can help me. You it would appear maybe my last chance. I will keep my fingers crossed that you did come across some info on him or you know some one that maybe able to help. He went to America in 1913 on the Lusitania and it shows at this time he is married. He then returns to America in 1914 on the ship Adriatic. I do believe he also did a radio show after 1935 for quite some time but do not know the name of that show. I do hope you can help in my search for my Great Uncle.

I also might add my great grandfather was Edwin Richard Barwick. He was also a Music Hall performer and appeared in the first Royal Command Performance. If you get the picture and Index to that even you will see him standing next to Pavlova. I would love to hear any information you may have found out about him. I do believe he was one of the first members of the charity named water rats, I know star was spelt back wards to get the rats part. Edwin did a lot of work for this charity in his day. What I would love to know is if there is any recording of Edwin Performing and if so how I would go about getting a copy or seeing any recording. I do have a photo copy of an old theatre bill with my grandfathers name boldly written on it. Again any help would be appreciated.

All the best and I look forward to hearing back from you in the near future

Kim Rayner

my email address is ruskimic@yahoo.com.au