Leslie Sarony

“I see, sir. Most disturbing.” “What did you say it was?” “Most disturbing, sir.” I snorted a trifle. “Oh?” I said. “And, I suppose, if you had been in San Francisco when the earthquake started, you would just have lifted up your finger and said: ‘Tweet tweet! Shush shush! Now now! Come come!’”

From Episode of the Dog McIntosh in the collection Very Good, Jeeves by P.G.Wodehouse (1930)

After a lengthy spate of insult humor, Old Mother Riley breaks into a song (which seems to have the refrain, “I lift up my finger and I say tweet tweet, shush shush, now now, come come”), and then dances about her shop, joined not only by the rental agent, but by two female neighbors, who have been functioning as a sort of provincial Greek chorus.

From Bela Lugosi (Midnight Marquee, 1995), in which Mother Riley Meets the Vampire (1952) is analysed by American academic John Soister

‘THERE’S a story behind every song, you know,” said Leslie Sarony. “In the 1920s I was appearing in Showboat at Drury Lane and one day I passed two showgirls in the corridor. They were going at it hammer and tongs, calling each other everything except ladies. So I went up to them and I said: ‘Now, girls, do what I do in a situation like this: I lift up my finger and I say ‘tweet tweet, shush hush, now now, come come.’ And so the idea for a song was born.”

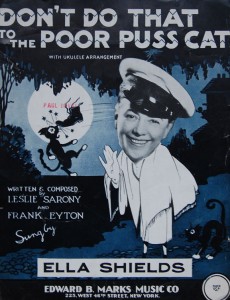

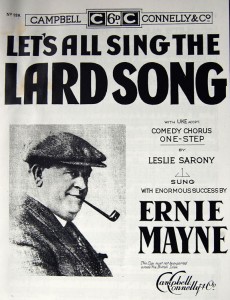

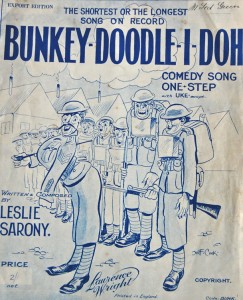

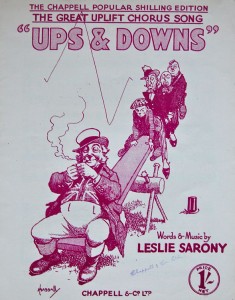

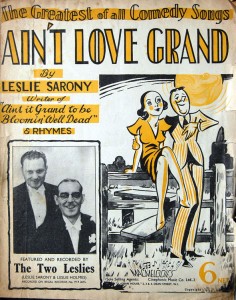

Sarony, undisputed king of the nonsense song, composed, performed and recorded even sillier numbers – hundreds of them between 1926 and 1939 – Don’t Do That to the Poor Puss Cat, I Caught Two Cods Cuddling, The Sizzle of the Sausage, Icicle Joe the Eskimo, Fat Flat Fish, Ain’t It Grand to be Blooming Well Dead, Wheezy Anna, The Wedding of the Garden Insects, I Found a Hard-Boiled Egg in my Love-nest, Umpa Umpa Stick it up Your Jumper, The Dicky Bird Hop and There’s a Song They Sing at a Sing-Song in Sing-Sing, to name just a few, the majority under his own name and others under whimsical noms de plume such as Q. Cumber.

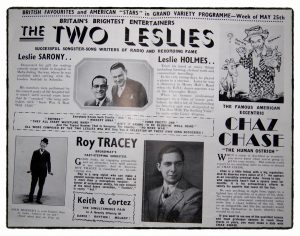

With vast numbers of variety theatres all over Britain, and a massive industry selling 78rpm records by the million, there was an insatiable appetite for novelty songs, and Sarony’s were sung, hummed and whistled on the streets and in almost every home in Britain in the 1930s. But the extraordinary Leslie Sarony was much more than a songwriter. As well as having around 400 published, he also shone as a recording artist, stage and television actor, comedian and dancer, and for many years was half of the bill-topping double-act The Two Leslies. His numbers were featured by great stars of the day – George Formby, Gracie Fields, Albert Whelan and Stanley Lupino – and he is the link between several of the artists in Voices of Variety: he wrote material that was recorded by Elsie and Doris Waters, Hetty King, Sandy Powell and Thanks for the Memory’s Randolph Sutton, and he appeared in music hall revival shows in the 1970s with Hetty, Sandy, Elsie and Doris and Nat Jackley.

As a lyricist, Leslie Sarony often saw possibilities in the most mundane of everyday items. In Gorgonzola, for example, he expanded the pungent cheese’s bacterial qualities to create a sort of useful household pet.

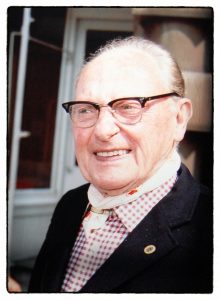

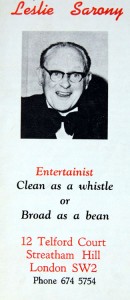

It’s really very handy when a dinner party comes; You leave it on the table and it eats up all the crumbs. Gorgonzola! Gorgonzola! Three cheers for the green, white and blue.I GOT to know Leslie quite well in the 1970s and found him to be great company, even though he could moan for England. He was a quick-witted, funny, scathing, outrageous, provocative little man, argumentative and highly opinionated, swift to take offence and slow to relinquish a grudge (some had lasted half a century). He was still working as hard as ever in his mid-70s – singing his famous songs, joking and dancing in summer shows, panto and old-time music hall productions, augmented by TV spots and straight theatre roles. He lived in a smallish flat in Streatham, London, crammed with knick-knacks, records and showbiz ephemera, and on the rare occasions he wasn’t working, he liked to go around the local pubs and clubs on talent nights, trying to spot stars of the future. He didn’t dwell on past glories but always looked ahead, which is probably why the wave of affectionate nostalgia that swept over anything to do with bygone entertainment in the 1970s somehow left Leslie Sarony untouched.

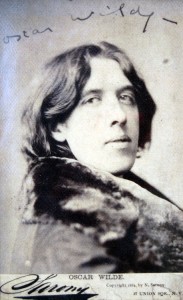

Born Leslie Legge Sarony Frye in 1897 in Surbiton, Surrey, the youngest of seven, he came from an extremely gifted family. A great-uncle, Oliver Sarony, was photographer to Queen Victoria, and his grandfather, Napoleon Sarony, was also a photographer, creating now-familiar images of Anthony Trollope, Mark Twain, Sarah Bernhardt, Oscar Wilde and many others. The Sarony brothers were of Prussian or Hungarian extraction, and their father emigrated to Canada around the time of the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon, a fearsome-looking little man sporting a bristling moustache and fez, moved to New York and initially worked as a lithographer, and Oliver emigrated to England and set up as a pioneer photographer in Scarborough. Napoleon visited him there, became interested in the art, and when he returned to New York he too became a famous society photographer. When he came to Britain to see Oliver he was accompanied by his daughter, Mary, who fell in love with and married William Rawston Frye, a portrait painter who had several of his works accepted by the British Royal Family.

Leslie Sarony’s sister, May, was one of George Edwardes’ original Gaiety Girls, a troupe of beautiful and elegant dancers who adorned West End shows clad in voluminous Victorian bathing costumes or the latest high fashion. “When I was kid at school my parents used to take us up to see May at the Gaiety,” Sarony told me. “She was married to an army officer and I sometimes stayed with them at weekends. They lived at Buckingham Gate, and I’d meet all the big stars like Gertie Millar and G.P.Huntley and they used to give me golden sovereigns – a fortune in those days.”

It was another sister, Mabel, who encouraged the little boy’s natural talents for singing and dancing. “She played the piano, and you know how families are with kids. They thought I was bloody marvelous because when people came round we always did a show. She used to play and I danced on my father’s drawing board.”

Mabel, May and his parents persuaded him to enter amateur talent competitions at music halls, which he invariably won. Some of the venues were rough places for such a small child to be in, but Leslie, with the courage and doggedness that would characterise his whole life, refused to be intimidated. “The old Shoreditch Empire had a special matinee every month or so for amateurs and semi-pros, and I don’t mind telling you that if they didn’t like you they used to give you the bird, and the stagehands used to hook ‘em off, round the neck. And I went on there and I did well and an agent came up to me and booked me for a week’s engagement at the Star, Bermondsey. Well, that was a jolly place, too, I can tell you. If anyone wore a collar and tie they got mugged!”

BEFORE he reached his teens he was a full-time performer. “The first time I left home and went on tour, starting in Liverpool, I was with a well-known music hall standard act called the Arthur Gallimore Trio. They were related to Florrie Gallimore, who was a well-known music hall star, on a par with Florrie Forde, and they led me a dog’s life. Used to keep me in this back room with no one to talk to. I was just a slave, and I used to go on and play this kind of page boy. I had to see to all the props and wait on them hand and foot.

“When I was with the Gallimore Trio we played Folkestone on the pier – they had a pier in those days – and I had to do a variety act, although I’d never done one, so I did a wallop to Alexander’s Ragtime Band. They played all the music halls, and I had to dress anywhere I could find. Some of the acts we were on with were very well-known. I always used to watch them. If you were interested and went up to them and said ‘How do you do this, how do you do that?’ they’d tell you, because they liked to see you taking an interest.

Listen here to three of Leslie Sarony’s biggest hits.

“Then I went into a troupe called Doc Park’s Eton Boys and Girton Girl. There were ten of us boys and one girl, and the man who managed the troupe said it’ll be a long time before you get anything as good as this. We were dressed in little bum-freezer jackets and looked as if butter wouldn’t melt in our mouths. It would, you know. And it did!”

He heard about auditions for a lavish revue at the London Hippodrome, Escalade. “It was a show that was done dancing up and down staircases. There was a race between the Alhambra, the Hippodrome, the Opera house and the Prince of Wales to put the first staircase show on. I went for an audition and I crept in. I was terrified. There was a big American producer called Ned Wademan and I went up and said ‘Excuse me, Mr Wademan. I’ve got no music but I do a routine and invent stuff,’ and he said ‘Go ahead’ and he let me go right through this routine and I got the job. Then it came to rehearsals and I hadn’t got a routine worked out. One morning Ned Wademan said: ‘Listen everybody, nobody’s goin’ to leave this goddamn theatre because the show’s goin’ on tonight!’ I said to the Musical Director: ‘What am I going to do? I’ve no routine worked out.’ And he said: ‘Don’t you worry – you keep dancing and we’ll keep playing’.”

He also went on the music halls as a single turn, and it was around this time that he became friendly with another of our featured artists. “Funnily enough, Sandy Powell and I were contemporaries. He was on the bill with me at the Bradford Alhambra doing a sailor act and I did an act with immaculate evening dress and a banjolele.”

When the First World War broke out soldiers in uniform used to call out insults to any young civilian men they saw in the street, implying that it was cowardice or lack of manliness that kept them out of the army. These were not challenges Sarony was prepared to tolerate and he tried to enlist but was turned down several times before he got in. “When I was in the First World War I was in The London Scottish and we went through France to Salonika. Incidentally, in France there was a very famous entertainment, an army show called The Barnstormers, and me and my pal joined it and we put on a smashing show but it only lasted for a fortnight because we were sent to Salonika and then I went down with dysentery.”

Sarony didn’t seem to want to dwell on his war service when we chatted – and little wonder. His son, Peter Sarony, filled in a few details for me: “He was one of the fortunate few who survived the infamous WW1 Battle of Messines on Hallowe’en 31st October, 1914, where he was a member of 1st Battalion the London Scottish, which was the first territorial infantry battalion in action against the Germans. It was slaughter. They had to hold the line, bayonets fixed, against the Germans as their rifles did not chamber the service ammunition provided!”

Not much to laugh at there, then, but there was an upside in the periods between marching, trying to sleep in mud-filled and rat-infested trenches and fighting for his life, sometimes in hand-to-hand combat with bayonets. “It was in the army that I found out that I could write songs,” he said. “I’d always thought how marvelous it would be to write your own songs and right from the start I always tried to create songs with a silly idea behind them.”

After the war he resumed his stage career in revues, concert parties and musicals and for a while it was tough going. “I used to work very hard for very little. Used to go fishing for coarse mackerel, for food. I was stranded. It does you good. I went to South America in 1921 and got stranded there.”

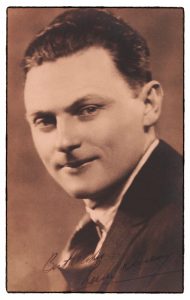

Then he began to get offers at a much higher level, with important song-and-dance parts in West End revues and musicals. In 1924’s Whirl of the World, which ran at the London Palladium for 627 performances, he had a show-stopping routine, Dancing Jim, and co-starred with Billy Merson, Nellie Wallace, Tommy Handley and Nervo and Knox. Jerome Kern’s Showboat at the Drury Lane Theatre four years later featured the original Broadway star, Paul Robeson, and saw Sarony in the key supporting role of Frank, singing the charming comedy number I Might Fall Back on You. “I was working on a bill at the Palace when someone saw me and booked me for Showboat – they’d already booked three comics for that part but they were all sacked. You had to be able to sing and dance and act as well, and they could do two things but not a third.”

He had the best comedy part, Chick Bean, in Rio Rita at the Prince Edward Theatre in 1930, and might have continued for the rest of his career in musicals, but various factors militated against this. As well as being very short, the impish-faced Sarony was perhaps not conventionally good-looking enough to play leads and presumably he didn’t want to be second fiddle in musicals for ever.

Here he is performing a fantastic eccentric dance routine in Rio Rita in 1930. The soundtrack has been added on, so the dancing is out of step, but it is still worth it for a glimpse of Sarony in his prime as a dancer.

Also, he had by the late 1920s begun composing songs for revues at a prolific rate – I Lift Up My Finger and I Say Tweet Tweet was written for the Stanley Lupino show Love Lies in 1929. And the songs he was writing were not about true love, loss, betrayal or any of the other staples of the West End stage. Music hall songs had always dealt humorously and earthily with the trials and tribulations of everyday life, and Sarony took this preoccupation with the mundane into territories of inspired madness. He wrote tuneful, catchy songs about fish, cucumbers, cheese, farming, pubs, sausages, cough sweets, darts, cake and cats. Or anything else that took his fancy as he doodled at the piano (he could neither read nor write music) or ukelele. One, Don’t be Cruel to a Vegetabuel, was about vegetable-abuse.

Fittingly, considering his gloomy fatalism, he had a minor speciality in bizarre songs about death; as well as the classic Ain’t It Grand to be Blooming Well Dead there was Three Cheers for the Undertaker and Why Build a Wall round a Graveyard? Ain’t It Grand was the first record to be banned by the BBC on taste grounds, and in spite of this went on to sell a million copies. Other titles sounded as if dreamed-up while in the throes of some kind of mild psychiatric episode: Po-Kee Oh-Kee Oh, Plinkerty Plonk, Skiddley Dumpty Di-Doh, Cor Luvaduck Crikey Coo Blimey. Some were in response to another composer’s song, such as his Jollity Farm, which referenced the earlier Misery Farm, written by W.H.Wallis and popularised by Tommy Handley.

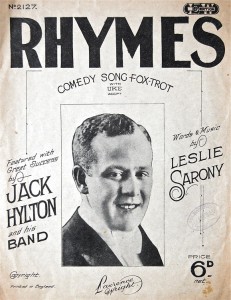

For several years Sarony wrote all the novelty songs for Jack Hylton’s Band, with which he recorded extensively. “Hylton would ring me around midnight and say: ‘We’re doing four titles tomorrow – be there!’ I’d sit down, write the songs, Hylton would have them orchestrated and we’d do them the next day. They were recorded straight onto the wax. If you got it wrong you had to do the whole thing from the beginning. No editing in those days. You were very popular if you made a mistake.”

Almost all of Sarony’s output was childishly ridiculous – “infantile,” his son Peter called these songs. “I think they’re clever, a lot of them,” he added. “But they are what they are, and I don’t think their value goes too deep. Some of them I don’t care for too much because they are repetitive. But he did write ballads that were not silly songs at all, and some of them are very nice indeed.”

Because of the breadth of reference Sarony was bringing to his writing in the late 1920s, the songs stood out as being different and special even in an entertainment scene that was hardly short of daft songs. The music halls beckoned, warm and vulgar . . .

To see Leslie in 1931 singing his Icicle Joe and tap-dancing, click here.

THERE have been many instances of artists who made their reputations in loftier areas of theatrical endeavour throwing it all up and going on the halls. Malcolm McEarchern was a classically-trained basso profundo from the concert stage before he gleefully embraced a new life as Mr Jetsam in the comedy act Flotsam and Jetsam. Bransby Williams had been a great Shakespearian before he went on the halls doing quick-change character sketches from the works of Dickens. And there were many other instances. Leslie Sarony had not exactly come from the legitimate side of the performing world, though his home background had been artistically innovative. Nevertheless, the music halls represented a step towards the lowest common denominator of the entertainment industry.

If you weren’t too snooty about high art, the halls provided regular income and the camaraderie of raffish fellow-pros as you toured the country. There were drinks to be had and girls to be romanced; there was the gratification of instant communication with a largely working-class audience. And, for a songwriter and recording artist, every appearance on a music hall bill could be used to plug the latest release.

“Youngsters today will never know what a real music hall was like. It had a magic about it. There’s no doubt that you had to be able to do something to earn a living on the music halls. You didn’t get on the bill unless you had something to offer. I went into all kinds of things – revues, concert parties, pantomime. You look at things then and you look at things now and you see how the rot’s set in. There’s no way to learn the job properly now. For light entertainment, the finest school was a concert party – they call them summer shows now. They were the finest schools. Concert party and rep.

“And all the artists were individualists. You never saw anybody copying anyone else. You knew that if you went to see a show that the acts were going to be different, and they had to be of a high standard to play in a music hall. Great artists. Great characters. Very generous. That spirit doesn’t exist any more. Now money is getting out of all proportion. It’s ridiculous. Yet today they are so mean. What do they want to do with it, die the richest man in the graveyard? I don’t say squander it around, but for goodness sake spend a bit.”

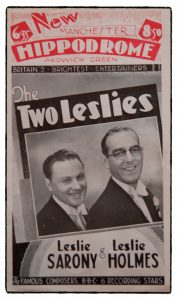

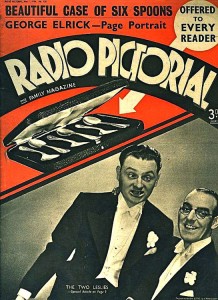

In 1935 he met Leslie Holmes and they teamed up as The Two Leslies, an act that topped bills for 11 years and featured in the 1938 Royal Variety Performance at the London Coliseum. “Leslie Holmes was a manager for a firm of music publishers and in those days music shops were a hive of activity – all these rooms and in every room a piano playing, and songs being demonstrated. I got to know him because his firm published my songs, and we got together and had a long partnership on radio and in the music halls.”

HOLMES, known as ‘the man with the laughing voice,’ was a tall, thin party with glasses, rather sinister-looking to my mind, and he had a dementedly cheery and avuncular manner. He played piano while Sarony told jokes and tap-danced around it, sometimes lifting his trouser-legs enticingly to expose his shoes and suspender-supported socks, the better for audiences to appreciate his nifty footwork. The duo harmonised on songs mostly written by Sarony such as Sweet Fanny Adams, The Dart Song and Teas, Light Refreshments and Minerals. When I first met him in 1971 and asked about his old partner I got a typically mordant response: “He’s a landowner these days. He owns a plot in the cemetery three foot by six.”

The Two Leslies enjoying Teas, Light Refreshments and Minerals. Click here.

Onstage they called each other ‘Mr S’ and ‘Mr H,’ and there was a running gag about Sarony always arriving late, when Holmes had already begun the act: “Come along, my little fellow,” ‘Mr H’ would humorously chide. “We used to be booked up a year ahead, always a year ahead,” said Sarony. “In the very early days stars used to be booked up five or six years ahead at an increasing salary. When I started there were 26 variety dates in London alone, without leaving the city.”

The Two Leslies years marked the peak of Sarony’s celebrity and short-lived huge wealth. “They were very, very big,” said his son Peter. “Each had a Jaguar car – ‘LS 1’ and ‘LH 1’. Then there was the SS Club, which stood for Sarony and Stanelli [entertainer famous for an act where he ran up and down a row of old-fashioned bulb-horns honking out classical tunes]. They had a place in the West End and it lost Pa a huge amount of money. I think he owned a substantial part of a greyhound stadium once, and 14 properties. He was the only man I knew who lost money on property. He wasn’t lucky in some of his choices as ‘friends’ – let me put it like that. He was not a good judge of people in that way. Some of his songs were huge sellers but somehow, although he had around 400 pieces of music published, the royalties were peanuts.”

The Two Leslies split up in 1946 when Holmes got tired of show business and left to become publicity manager for The News of the World. Sarony took on a new partner, Michael Cole, but it didn’t work out and for the rest of his long career he was a solo performer. The astonishing versatility that had taken him to the top was also something of a handicap as the halls started to decline, and there was a time in the early 1950s when he floundered a little. What exactly was he: a comedian, a singer, a dancer, an actor, a songwriter? He was all these things, of course, and excelled in each, and the public sometimes had difficulty getting a fix on him as he darted from one to another.

This was not helped by Sarony’s own attitude. He was very blunt and outspoken and was not at all a jolly character unless there was an audience around. In our first conversation he was less than complimentary about most of the other old stars I was interviewing around that time, considering that some had outlived their usefulness as performers. He did admire Hetty King, however, and talked about her artistry with great respect, though he felt obliged to add, in typically Saronian fashion, that as a person she was “completely barmy.”

To his credit, he always regarded himself in a very un-starry way as just a working pro who could turn his hand to anything asked of him. And he wasn’t particularly picky. “Now this is going back a few years, to 1951,” he complained to me. “I created a puppet character for BBC television and after one transmission I got all these letters from kids from all over the country. I had something really big there, and the kids really loved it. I did two more shows and then along came this bloody woman and scrubbed it all. Now that could have been as big as, say, Sooty or any one of those things.”

He never, ever stopped composing. “Not all the songs he wrote were published,” said Peter. “I would say only about 25 per cent. He wrote thousands of songs. His mind was buzzing the whole time. When we were in the car and we’d be travelling around he’d always be humming or whistling something and then he’d get a theme and he’d actually be composing as he drove along. Then later he’d get somebody in and he’d hum it to them and they’d write it down. He could play, but he could only play by ear, and he mainly used only the black notes. And he took a ukulele with him everywhere. He was naturally a very, very musical person.”

Sarony married actress Anita Eaton when he was in his forties, though they later divorced, and had three sons. Peter is a well-known gunsmith, Paul a film producer, and Neville a QC. What was he like as a father? “He was hopeless with children,” said Peter. “Hopeless. And he was absent as a parent for much of the time because he was on tour. So he didn’t really have a normal father-and-son relationship with his boys because most of the time he wasn’t there. But he was a great tinkerer and he would make these things. I remember once when we were living in Huddersfield – he’d taken the family there to evacuate us during the war – he turned up with two tommy guns that he’d made using old wooden football rattles. He was very clever like that. He loved tinkering in his shed with all his tools.”

In the mid-1950s he became more involved in straight acting on television and in films, including a glorious portrayal of Mr Pinkwhistle in the movie Noddy in Toyland (1957). Through the 1960s he was a regular on television, playing large and small roles in series such as Boyd QC, Crossroads, Edgar Wallace Mystery Theatre and Z Cars. He was a semi-regular in the comedy series Nearest and Dearest, set in a Lancashire pickle factory, though he told me he loathed its star, Hylda Baker. “Nearest and vilest, I used to call it. It’s funny – I’m Cockney but I’m never given Cockney parts. I always have to play North Country.”

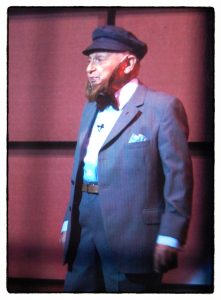

By 1972 he was well-esconced with the other veterans in Voices of Variety on the old-time music hall circuit. “At seaside shows I wear a check suit of loudish design. As the band launches into I Lift Up My Finger and I Say Tweet Tweet I stroll on with one index finger upraised.”

After a chorus of this gloriously-fatuous ditty, Sarony would rattle off a series of extremely long and complicated jokes, many of them concerned with speech defects (always good for an easy laugh back in the day). His movements on stage were precise and formal, even dainty. The expressive hands seemed to betray his artistic and mixed-race ancestry as he neatly itemised the components of a joke with brisk, Cagney-like chops of the air in front of him. He was not one of those matey comics who demanded love; Sarony was more remote, seeking to captivate audiences with respect for his total professionalism.

He sang a couple more of his own compositions, then reached the climax of his act, a weird routine he had been performing since the early 1930s and which fell just the acceptable side of bad taste. “Imagine a sailor,” he said, donning a false beard and mariner’s cap, “who has only one leg but loves to dance. It would look something like this.” A cheery little song about this disabled seaman, Old Peggoty, followed and then Sarony suddenly clutched his left thigh with both hands, keeping the leg stiff as a ramrod. Using the dead leg to jerk himself around the stage, his right foot twinkled in an expert and vigorous tap routine as he capered off into the wings to tremendous applause.

To see him perform the Peggoty dance in another Pathe clip, this time from 1933, click here.

I remember him in an old-time show at Swindon, where he shared the bill with Hetty King, Sandy Powell and Fred Emney. He played a round of golf in the morning, acted in the afternoon matinee of Peter Pan then went on stage in the evening to do his variety turn. I was staying at the same hotel, and when he got back from the theatre he would often sit at the piano in the lounge regaling the other guests with songs and bawdy stories until the early hours. “You couldn’t exhaust Pa when he was in his element,” said Peter. “He had amazing resilience.”

Here’s Leslie Sarony late in life – well into his 80s – in a TV appearance where he sings The Old Sow (a traditional folk song involving bizarre vocal effects that he made his own) and his classic Aint It Grand to be Blooming Well Dead.

“Some stupid people ask me when I’m going to retire,” Sarony told me contemptuously, “and I say: ‘What for? What do I do if I retire?’ If I were no longer capable, obviously I wouldn’t attempt it, but I can assure you that nobody engages me out of sympathy. It’s a bloody rat-race. But, touch wood, I can do practically anything, and there’s very few people who can say that my voice has changed. And I play better golf than I have ever done in my life. I wouldn’t walk a yard normally but I’ll walk round a golf course all day. I can do two rounds and give 20 years to some of them. I’m seventy-four. It’s ridiculous.”

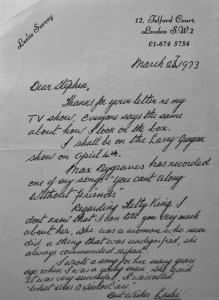

I LIKED Leslie Sarony a lot, and kept in touch with him right through the 1970s, sometimes through personal meetings if he was working near Manchester, or I would visit him in Streatham if I had to go to London, and we exchanged letters and cards from time to time. He send me a card every Christmas, too, and he also had a kind of little business card, with a the legend ‘Leslie Sarony, Entertainist. Clean As A Whistle or Broad As A Bean.’ In 1974 he was knocked down by a motorbike outside a theatre where he was appearing in Eastbourne: ‘I’ve had a very bad time,’ he wrote. ‘I can’t dance or play golf. But I’m making good progress.’

He was in a few straight parts on the West End stage – he played the caretaker in Echoes From A Concrete Canyon, Dada in Entertaining Mr Sloane, and he was also in The Bear, by Anton Chekhov at the Royal Court Theatre – and in 1976 was engaged to play Nagg, the legless character who spends his whole time onstage peeping out of a giant dustbin in Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, also at the Royal Court. “Well, it’s something a bit different, isn’t it? I was pleasantly surprised that I wasn’t received with resentment by the company. I thought they would be thinking ‘Fancy bringing in this old bastard,’ but in fact everyone has been most helpful and charming. Perhaps it’s not such a strange bit if casting, though. All comics are to some extent character actors.

“The reason it’s so difficult is that a lot of the character is built up through inconsequential chat. There’s no shape to some the dialogue. Beckett will talk about something, then leave it, then go back to it then forget it then go back to it again and finally end up talking about something entirely different, so it’s not easy to memorise. It’s like trying to learn the bloody phone book.

“But I’m very fortunate in that I still have a good memory and I am also able to assimilate what people tell me. Which is just as well, because you can’t mess around with Beckett. You have to play it exactly as it is written. When I arrived at the theatre I said ‘Now I’m here to do as you want – tell me how to do it,’ and the director said ‘Try to convey what you think it ought to be,’ which was a bit daunting because at that point I didn’t understand a bloody word of it. I do now, though. You find yourself completely drawn into Beckett’s strange world. Anyway, Beckett himself saw me doing it and was apparently satisfied.”

WHILE the name of Leslie Sarony may have become unfamiliar to new generations by the 1970s, within the entertainment business he had become a living legend, not only for his huge achievements in so many areas over so many years, but because he was the undoubted star of the annual Vaudeville Golfing Society Dinner, a hugely popular and much-anticipated annual event for pros. At the cabaret after these dinners, with the all-male audience well-oiled, Sarony would deliver a set of astounding filthiness, mostly parodies of well-known songs – The Fanny With the Fringe on Top, Pud Pud Pulling Your Pud (to the tune of Flanders’ and Swan’s The Hippopotamus Song) – and his own material: Easy Anna, a version of Wheezy Anna. All through his career a strain of salacious ribaldry ran through his material, though he was able to give full reign to it only in the company of fellow-professionals. “He was such a dirty little man,” a woman I knew, Dodie, who had been a showgirl and friend of his in the 1930s, recalled fondly. And Elsie and Doris Waters belied their cosy public image when they told me they found his x-rated material hysterically funny, so evidently he didn’t always restrict this side of his output to gatherings of the lads.

Occasionally Leslie Sarony might seem a bit sorry for himself when we met, but it was more likely that was simply enjoying yet another grumble. “People are always asking why don’t I make an LP record,” he said wistfully once. “That rests with the powers-that-be. When I’m dead and gone I suppose they’ll all be falling over themselves to reissue all the old 78s on an LP. That’s the way show business works. I am lucky, as my voice hasn’t changed. But it’s a pity I can’t re-do them myself, with up-to-date arrangements.

“My lack of vitality sometime depresses me. I can’t go round a golf course like I used to since my accident. And I think of some of the music hall people, now passed on, who didn’t know when to throw in the towel. People like Randolph Sutton and G.H.Elliott, who insisted on appearing before the public when they were well past it.”

The little man’s impish face darkened and his lower lip stuck out in that defiant and pugnacious way of his. “God forbid I should ever be like that,” he said vehemently.

Ain’t It Grand to be Blooming Well Dead

LESLIE Sarony did get to re-record some of his old hits with modern arrangements for an LP in 1980, and soon afterwards was awarded a Golden Tuning Fork by the Songwriters Guild of Great Britain for his lifetime’s achievement as a composer. Shortly before, at the age of 82, he had scored a big success when he took over from Bert Palmer as the hilariously doddering Uncle Stavely (“I heard that! Pardon?”), who carried his old army pal Corporal Parkinson’s ashes round in a little box hanging from his neck, for the fourth series of Peter Tinniswood’s Yorkshire comedy about the Brandon family, I Didn’t Know You Cared, on BBC television. Other appearances included Victoria Wood: As Seen on TV and Minder, and in 1984 he had a showy bit part as the Gatekeeper in Paul McCartney’s Give My Regards to Broad Street. Also in 1984 he was on a television variety bill broadcast from Manchester. His friend Roy Hudd takes up the story:

“I compered the show and he wasn’t very well at all. During the show he sat on a chair in the wings, looking very old and frail, but, as the band played I Lift Up My Finger, he jumped up, pulled the front of his blazer down, strode on and proceeded to paralyse them with an eight-minute medley of his hits. When he came off I could see he’d had enough. He went to sit down but the floor assistant grabbed him and said: ‘I’m afraid we missed a couple of shots. Will you do it again?’

“ ‘No, he won’t,’ I said, but he pushed me aside and did the whole spot again with, if possible, even more energy than the first time. He came off and I apologised to him for them making him do it twice. He said: ‘Listen – they wanted it again and that’s that. I’ve kept them sweet. Very important.’ He added with a twinkle: ‘You never know what it’ll lead to’.” (1)

Here’s a clip from I Didn’t Know You Cared, with Uncle Stavely rehearsing his duties a pageboy at Mort’s wedding. Others in the scene are Liz Smith, Liz Goulding, John Comer, Keith Drinkel and, as Mort, the great Robin Bailey.

A few months later Leslie died of cancer in a London hospital. Active almost to the very end, at 88 he was the oldest working actor on Equity’s books. He had been an ‘entertainist’ for over three-quarters of a century. In December 2010 The Guardian asked musician Jools Holland what he’d like played at his funeral, a stock question in the paper’s Saturday magazine personality profile. Ain’t It Grand to be Blooming Well Dead, said Jools, by Leslie Sarony. And when beloved British actor Timothy Spall was asked the same question on March 15 2014 he answered: ‘Dido’s Lament from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, which is very sad, followed by Ain’t it Grand to be Blooming Well Dead, a music hall song that is blackly funny.’

stephendee

| #

Doesn’t ring a bell with me, Stefan, tho it’s a very typical Sarony line. Anyone? Stephen

stefan Beard

| #

Just been reading the Leslie Sarony piece. Absolutely fantastic. Well done. A question if you don’t mind. Does anyone know the the title of the Leslie Sarony song that has the line “Oi ! how you gettin’ on? ” in it ?

ruskimic

| #

I do hope you can help me. I have been searching for many years for my Great Uncle Mr Albert Edward Rayner who went under the name of Dan Rayner. I believe he worked the Music Halls but I do know for sure he worked with Fred Karno. When Charlie Chaplin left Fred in America over a Pay dispute the American backers of the tour insisted that my Great Uncle Dan Rayner be called over from England to take Charlie Chaplin’s Place. It appears Dan was liked more at that time in America than Charlie was. Another man in the troupe at that time was Stan Laurel. When the show folded Dan was asked along with Stan to stay in America. As we know Stan stayed and found he fame and fortune. Dan however chose to return to England. He was last that I can find in a play Dick Wittington at the Empire Theatre advertised in the a local paper in Durham in 1948. Unfortunately I have not been able to find when or where he died. I am hoping that maybe on your search you came across some info on Dan Rayner. I live in Australia so am unable to search all the death records for England with out it costing me a fortune. So any help you maybe able to give me would be really appreciated. I know he went to America twice and once to Australia and also once to South Africa. I do know he was married to a lady named Barbara Robinson and they had a son Conrad Paul Rayner but I have been unable to find any thing out about these two members of his family. I do know they separated before 1935 and he lived with another lady named Phyliss but as to her last name I have no idea. I have been searching for nearly 10 yrs now and I don’t think there is any thing left on the net that can help me. You it would appear maybe my last chance. I will keep my fingers crossed that you did come across some info on him or you know some one that maybe able to help. He went to America in 1913 on the Lusitania and it shows at this time he is married. He then returns to America in 1914 on the ship Adriatic. I do believe he also did a radio show after 1935 for quite some time but do not know the name of that show. I do hope you can help in my search for my Great Uncle.

I also might add my great grandfather was Edwin Richard Barwick. He was also a Music Hall performer and appeared in the first Royal Command Performance. If you get the picture and Index to that even you will see him standing next to Pavlova. I would love to hear any information you may have found out about him. I do believe he was one of the first members of the charity named water rats, I know star was spelt back wards to get the rats part. Edwin did a lot of work for this charity in his day. What I would love to know is if there is any recording of Edwin Performing and if so how I would go about getting a copy or seeing any recording. I do have a photo copy of an old theatre bill with my grandfathers name boldly written on it. Again any help would be appreciated.

All the best and I look forward to hearing back from you in the near future

Kim Rayner

my email address is ruskimic@yahoo.com.au