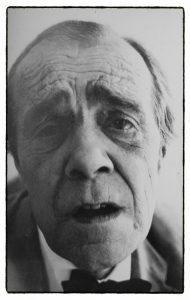

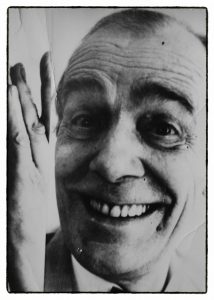

Max Wall

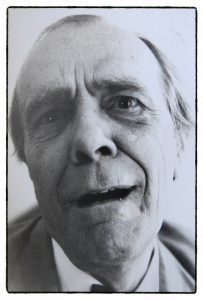

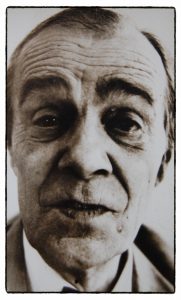

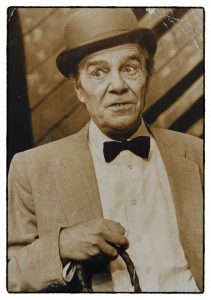

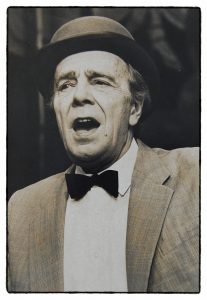

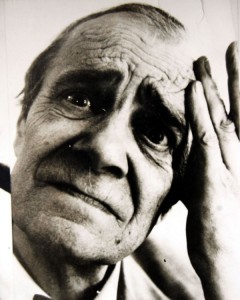

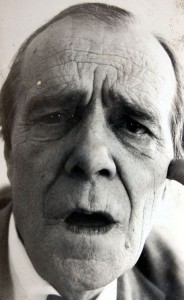

HE was the funniest comedian I ever saw, and one of the most tragic men I ever knew. Battered, truculent, often a bit drunk, ridiculous in his bedraggled wig and motheaten tights, this little music hall gremlin would stare insolently at the audience. “Max Wall standing before you, ladies and gentlemen. In the flesh, not a cartoon. Man’s answer to the peacock.”

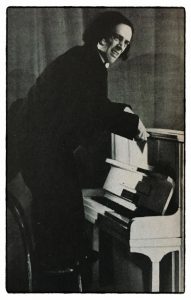

Alone there in the spotlight in his absurd costume and outsize boots – “these heels are built-up, you know; they give me that extra two inches I’ve always wanted,” he would declare with a revolting leer – he worked the swells and troughs of the audience, starting from cold every night, moulding onto the dusty bones of some corny old routine. “Professor Wallofski’s the name, well known in the field of classical music, and also well known in the field behind the gasworks. But my visits there . . . get fewer.”

Alone there in the spotlight in his absurd costume and outsize boots – “these heels are built-up, you know; they give me that extra two inches I’ve always wanted,” he would declare with a revolting leer – he worked the swells and troughs of the audience, starting from cold every night, moulding onto the dusty bones of some corny old routine. “Professor Wallofski’s the name, well known in the field of classical music, and also well known in the field behind the gasworks. But my visits there . . . get fewer.”

He laid bare the mechanics of his craft for all to see. After a silly little rhyme near the beginning he would announce: “That’s the sort of thing I do. You may think I’m wasting my time doing it.”

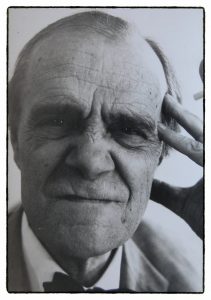

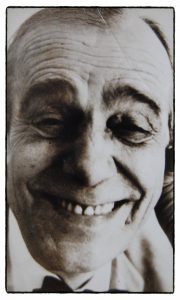

But when he was in top form, his command of an audience was total, almost hypnotic, even though by the 1970s his act, at once arrogant and self-contemptuous, had become so steeped in seedy irony that it was almost a definition of deconstruction before the term became common: a cheap, tatty old comedian telling terrible jokes, strutting and mincing – “I’m going to walk up and down for you now, and stick my bottom out, and you will find it very, very attractive” – and at the same time standing apart from the performance and mocking it. “It’s all a horrible send-up really,” he told me.

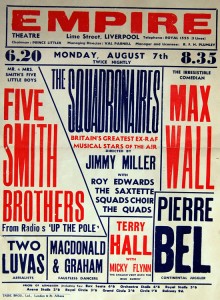

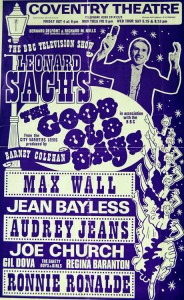

Max was at his lowest professional ebb when I first met him early in 1972. The legendary clown had once been one of Britain’s richest entertainers, at the height of his fame playing golf with King Edward VIII and socialising with aristocracy. He had lived in mansions and owned three Rolls-Royces. Before a scandal fanned by the press wrecked his career, he had starred on Broadway and in lavish West End productions and had his own TV series. Now he was just finishing a season as Mother Goose in panto at a tiny civic theatre in the Cheshire village of Romiley. And his date-book for the rest of the year was empty.

“I read in some paper that I am now in ‘semi-retirement’,” he told me with the intense gloominess that was his default stance on just about everything. “Well, what is retirement? I suppose you could call it that, but if somebody came along and said we want you to this, that and the other, then I’d do it. Because I still love the business and – most of the time – I feel as young as I was twenty-five years ago. I can still do all my stuff, and I feel I’m not dated. When I appeared at a music hall show at Greenwich a few months ago all the young people – hippies – gave me a standing ovation. The younger generation seem to like my stuff. It’s very hard to see why I’m out in the cold.

“As long as I’m capable, and people find me entertaining, I’ll do it. I shall come out of retirement – if indeed I am retired – if people want me. Retirement is horrible, anyway. I’ve been at this all my life, and as long as I’m capable I’d like to carry on. But after this show it’s all in the lap of the gods. I shall go home, and that will be it. In our business we’re all like Micawbers, waiting for something to turn up.”

He was thoroughly enjoying the panto, though, he told me miserably. “I love pantomime because I love children, and it suits me because of all the mugging and grimacing and falling around. It suits my style of work.”

Max was 64 years old, and for the previous two decades his private life had been an open book of wrecked marriages, disastrous relationships with other women, arrests for public drunkenness and drink-driving, and estrangement from his five children. There were more intimate problems, too, and he didn’t shy away from confiding them when he had a few drinks on him: “I can’t even get it up any more,” he told one startled journalist. (1)

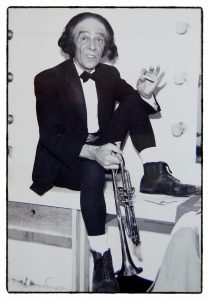

He was also battling the taxman, and soon after our first meeting his only possessions as an undischarged bankrupt would consist of a couple of suits, his props, a guitar, a transistor radio, a typewriter and a few books. The ‘home’ he referred to was a cheap bedsit at Number One, Grote’s Buildings, in London’s Blackheath. When his second wife, ex-beauty queen Jennifer Chimes, had walked out on him a few years before she had left a note that said: ‘You will end up in one room, alone, with nothing.’

He had come close to suicide several times. Once he went into the garage of the house in Jersey he had shared with Jennifer, closed the doors, started the car engine and took a heavy dose of sleeping pills. “But just before I lost consciousness, some greater power stepped in and said: ‘Don’t be a cunt, Max’.”

During our conversation at Romiley, there was from time to time an insistent banging on the dressing room door, which he had carefully locked as soon I was inside, sometimes accompanied by furious cries of: “Open up, Max. Let me in, you bastard!”

Whenever it happened, the great comedian just flashed his ghastly ill-fitting false teeth at me, shrugged helplessly, and carried on talking. I was told afterwards by the theatre’s manager that Max had earlier confiscated some drugs from a woman who might have been his third wife, from whom he was thought to be separated, or a new girlfriend. The manager said she was about 35 years younger than Max and an exceedingly angry and troublesome person.

By early 1972 Max Wall was virtually forgotten by the public and written-off as a funny-walking disaster by most managements. But then something wonderful happened for this magnificent comedian, surely one of the finest Britain has ever produced. And I helped kick-start the process, in an extremely modest way. The day my interview with him appeared in The Guardian, the manager of the rock band Mott the Hoople got on, looking for a contact for Max. They wanted to take him on tour.

With nothing else in prospect, Max accepted, and while some of the gigs were not too successful, he did at least receive a lot of positive publicity and was able to bring his gifts to a new – if sometimes unappreciative – generation. “They told me you’d throw things if you liked me,” he would shout as beer cans rained down on him from outraged Mott the Hoople fans.

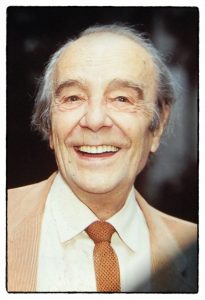

All the same, it was the start of The Big Comeback. The following year his name was back in lights in the West End after a smash-hit appearance doing his old routines in the musical revue Cockie! and he was being hailed by The International Herald Tribune as ‘quite simply, the funniest comedian in the world.’

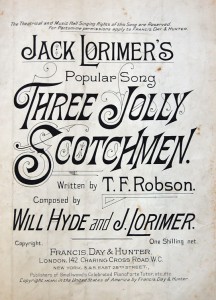

HE was born Maxwell Lorimer in Brixton, London, in 1908. His father was not “the Great Wall of China” as Max liked to claim in his act but Jack Lorimer, a noted Scots comedian, and he made his first stage appearance at the age of two. He wore “a wee kilt” as befitted the son of an artist billed as ‘The Hielan’ Laddie.’ His mother, Stella, also a performer, was a stifling influence on him for much of his early life, and although he came to resent her, Max, passive by nature, allowed himself to be dominated.

“My parents were in the business. My mother, father, grandmother, grandfather. My grandfather did a bit of comedy but mostly it was instrumental stuff. My grandmother was a dancer. This would be in the early days of the halls, the 1860s. My father was quite a big star, but he was an alcoholic and died when I was quite young.”

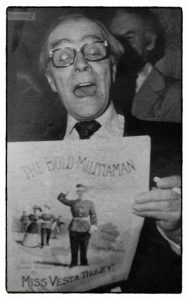

As a child he toured Britain’s music halls with his parents, meeting many great stars and being fussed over by other women on the bill. “I am pretty sure that Marie Lloyd was among my stage aunties. My earliest memory of her is hazy, but it is of me sitting in the wings of some theatre somewhere in England, and watching her perform. Needless to say, I was a very small boy at the time, but one much given to pulling faces. You could say that I had jerky mobile features as opposed to the calm countenance. It reached the point where Marie Lloyd asked my mother: ‘What’s the matter with your kid, then – ’as he got bleedin’ St Vitus’ dance?’ She was an earthy character, of course, with a natural, ribald, Cockney turn of phrase.” (2)

By the start of the First World War the marriage of Stella and Jack was in trouble, though they continued to work together, and Stella had taken up with Harry Bentley, a successful song-and-dance man. Bentley’s real name was Harry Wallace, and it was from him Max got his stage name: half of Maxwell and half of Wallace. He always cited Harry Bentley, who was to become his stepfather, as one of the most positive influences on his life.

IN 1916, while Jack and Stella were en route to South Africa, the Germans sent a Zeppelin over London. Just before it was shot down by anti-aircraft fire, it released an aerial torpedo and a gas bomb. Both fell on the family’s Brixton home, destroying it. Max and his older brother Alec were buried in the rubble but were saved by being trapped under the iron bed in which they had been sleeping, which overturned to form a protective platform for the brickwork that crashed down. The gas bomb fell on another part of the house where his little brother William, known as Bunty, was sleeping with an aunt who was minding the children. Both were killed. For the rest of his life Max Wall was haunted by flashbacks of hearing rescuers clearing away the rubble to get to him and Alec, and shouting for help as chinks of daylight appeared.

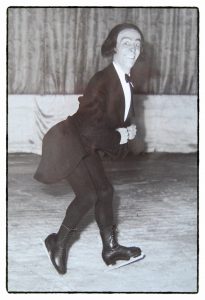

His earliest idols were Little Tich and the great Swiss clown, Grock, both grotesques who milked pathos from a bizarre appearance. When he was fourteen, Max became a full-time performer, billed as ‘The Boy with the Obedient Feet’ or ‘Max Wall and His Independent Legs’ and he first attracted attention in the 1920s as an acrobatic dancer.

Here’s the only existing film of Little Tich.

He toured Europe with Maurice Chevalier and Mistinguet, and appeared on Broadway with Milton Berle and Helen Broderick in Earl Carroll’s Vanities of 1929. “I went as a dancer and I finished up as a comedian. I stayed in America for about eighteen months and then I came back here as a comedy act.”

But managements in Britain persisted in seeing him as a tap-dancer who told a few jokes, rather than a stand-up who also danced. “You see, they liked people to do only one thing; they didn’t want you to succeed at anything else. And I was in a pigeonhole as a dancer. But it seems that one makes a success in spite of people rather than because of them.”

The following year he took part in the Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium. After this exposure he kept pestering managements to allow him to introduce more verbal comedy into his eccentric dancing act, but it was not until a few years later, in the heyday of radio, that producers began to appreciate the potential for drollery in those oozing vowels and nasal, staccato consonants.

“I started as a dancer: acrobatic dancing, tap dancing, funny dancing. I still use it all, as and when I can. A bit later, when I got better-known, I used to take my own show round the Moss Empires circuit – a stand-up spot, you might call it, and I also had a guitar-playing spot. I always did a spot in the first half and one in the second, and I created the Professor Wallofski thing for the second spot. You know, the character with the long hair, tights and boots. It was a satire on the old composers and pianists.

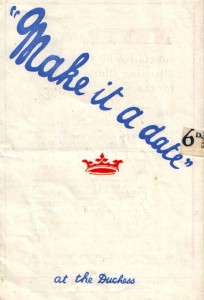

“People tell me my Professor Wallofski is a great grotesque, even in the tradition of Grock and Dan Leno. It’s become that. The first time I did it was at the Duchess, opposite the Drury Lane Theatre Royal. It was in a thing called Make it a Date. I wore the badly fitting evening dress and the short trousers. That was the start of it, and then I went to The Empire, Leicester Square. My agent suggested that I wear tights instead of trousers, to make fun of the resident ballet. So I did that and, of course, it went down terrifically well and I’ve kept it ever since.

“Now I’m stuck with the Wallofski routine. It’s been an annoyance from time to time. It’s such a silly act. You know, I wouldn’t couple myself with Charlie Chaplin – I wouldn’t do such a thing – but it’s a similar pattern. Chaplin was known for his baggy pants and bowler hat and whenever he tried to break away, it didn’t come off. And I’m known, in this country at least, as Professor Wallofski. Sometimes when I play clubs, they want me to wear the costume, even though there’s no piano to do the proper act. It’s become like a uniform.

“But I was a fine dancer. It took me fifteen years to learn to dance properly. And from that has come all the funny walks I do. The acrobatic stuff made me very loose-limbed, you see.”

IT was after Max Wall had been invalided out of the RAF in 1943 that he because a top radio name. BBC comedy producer James Casey, son of the great Geordie comic Jimmy James, once told me that his father defined a true comedian not as someone who necessarily says funny things, but as someone who says things funnily. This was certainly true of Max, who adored Jimmy James: “I used to love him. To me he was a marvellous man.”

Max could get a laugh with the line “I arrived tonight in a pantechnicon,” communicating to the audience his relish at simply articulating the word. Often the things he said were not jokes at all but surreal ways of dealing with mundane events – “a little hole sticking up,” he would explain after pretending to stumble. All the same, he did write some very fine gags. A particular favourite is still much-quoted: “Show business to me is like sex. When it’s wonderful, it’s wonderful. And when it’s terrible, it’s still all right.”

After many guest spots in top shows of the day, his own radio series, Our Shed, began a successful run in 1946. Supported by a troupe of reliable comedy actors billed as “Max Wall’s Trained Troupe of Performing Zombies”, he would start the show each week by dramatically declaiming: “Ah – but they do things differently there!”

Cast (in unison): “Where?”

Max (in silly kid’s voice): “Our shed!”

A clip of one of his routines from the 1940s. There’s a great little tap dance at the end.

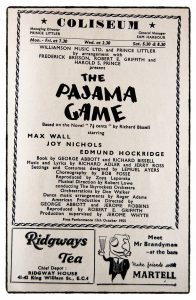

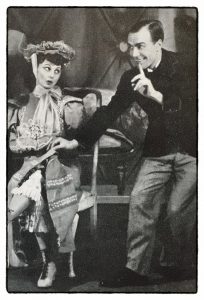

He was also starring in successful West End shows – Present Arms (1940), Panama Hattie (1943), Hoopla (1945) and Make it a Date (1946). A decade later he was still at the top, starring in the hit musical The Pajama Game, which ran for 578 performances at The London Coliseum, and The Max Wall Show on BBC television.

To the public, the little comedian’s home life must have seemed blissful. A reporter from the weekly magazine Tit-Bits visited Max, his wife Marion Pola, a former dancer, and children in the mid-1950s and wrote: The kind of private jokes you find in all the nicest families flourish with the Walls. After Max and his wife, Marion, had their first son, Michael, it seemed kind of natural to make a corner in names beginning with ‘M’, and there are now Melvyn (aged nine), Martin (nearly five) and the four-month-old twins Meredith and Maxine.

In the same way, because the Walls, like other couples married during the war, were eventually thrilled when they found a house with four walls of their own, they decided to call it just that, only Martin arrived and made it ‘ Five Walls’.

But in reality all was not at all well behind Seven Walls. We don’t know what went on, obviously, but whatever it was seems to have been quite dreadful. In later years Max hinted that he had been a victim of domestic violence. He admitted he made many, many mistakes. What is incontrovertible is that somehow all his children became alienated from him, and he remained more-or-less estranged from them for the rest of his life. One, at least, absolutely loathed him. Eldest son Michael said thirty years later: “I’ve nothing but contempt for him. As an artist he is a genius but as a man he is a despicable failure. I never want to see him or be associated with him in any way. I detest him so much that I won’t even use his name.” (3)

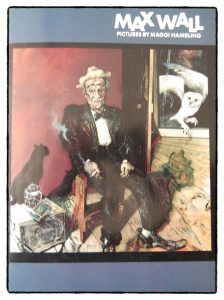

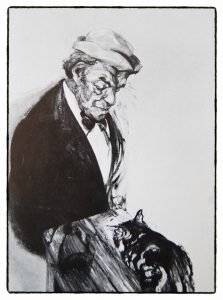

THIS was the black void of awfulness at the core of Max Wall’s being. He looked sad because he was sad. The comic desperation and melancholia we found so captivating on stage were projections of a profound inner desolation. Everybody in the latter stages of his career, after the comeback, loved ‘Max Wall’. He was sometimes billed as ‘The Irresistible Comedian’. But nobody in his private life, it seems, cared much for Maxwell Lorimer. Not even his children.

In 1955 he left Marion and became involved with Jennifer, who was the current Miss Great Britain and 26 years his junior. She, too, was married, and had two children. The popular press of the day, with the awesome sanctimony and hypocrisy for which they were renowned, went for the jugular (when he forgot the birthday of his twins, The Daily Sketch sent round a carload of cuddly toys to Seven Walls ‘so they wouldn’t be too disappointed’).

“They say that for an entertainer there’s no such thing as bad publicity. I’m not so sure. But what people didn’t know at the time was that I was completely broken up. I was in a very bad way mentally and my nerves were screeching out. Perhaps my attitude to the press was not what it should have been. I antagonised some people, this is possible, but you can’t have people sitting in judgment on you. If I had been capable of greeting the press laughing and smiling and saying ‘come in, have a drink; look, this is what it’s all about . . .’, they might have played it down a bit. But I just couldn’t do it. Human nature, I suppose.”

Max and Jennifer were married in 1956. In 1957 he collapsed on stage and suffered a nervous breakdown. Jennifer left him, but there were reconciliations. His work deteriorated and he often appeared on stage drunk. In 1960 he got the bird for the first time in his career; an engagement in Aberdeen was ended after one night ‘by mutual consent’. In 1962 he walked off the stage at a working men’s club near Stoke. He divorced Jennifer for desertion the same year.

Then, in Morecambe, he met Christine Clements. “I was up there doing a summer season with Nat Jackley. She was working at the dolphin show at the Marineland and we met at Nat’s birthday party. She was a pretty little thing. I got interested and that was it.”

In his autobiography, Max’s chapter on his marriage to Christine, who was 33 years younger, consists of two sentences: ‘I’ll never forget my third marriage. Don’t think I haven’t tried.’ The chapter is headed: ‘A JOKE.’ Comedian Roy Hudd once recalled: “Max’s association with the opposite sex always gave him trouble and I remember standing next to him in the Gents in Grosvenor House. Looking down, he muttered in that unmistakable voice: ‘You, you little swine – you’re the cause of it all!’” (4)

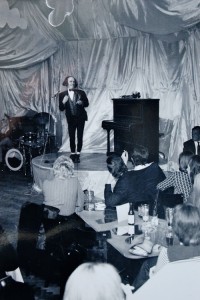

I met this aggressive and morose man a few more times during the next couple of years, and he generally seemed vaguely glad to see me, although I was never sure whether he remembered exactly who I was. He was a fund of scandalous showbusiness stories and I enjoyed his company, except when, as sometimes happened if he’d had a few, he became unreasonable or sank into maudlin self-pity. Once, when Guardian photographer Don McPhee and I were drinking with Max and singer Karl Denver backstage at a nightclub at Denton in the North of England, he ran out of his particular brand of menthol cigarettes, of which he smoked 50 a day, and refused to perform until more were obtained. When the cigarettes were finally found and he went on, drink had robbed him of his timing and he was sour and unfunny. The audience had waited more than an hour for him, and was not best pleased.

It is interesting, and poignant, to look at clips of Max Wall from the 1940s. There he is, happy and confident in his nifty suit and little trilby hat, rather handsome, cracking gags and rolling his eyes, doing impressions, singing whimsical songs and tap-dancing so brilliantly. The Professor Wallofski he portrayed then was comical rather than sinister, the wig shaggier, the smile sunnier, the gestures broader and less crablike.

Now look at the Wallofski of the early 1970s. He’s visibly aged, obviously, but see how much the Professor has been diminished by the years of disappointment and neglect. He’s like a gargoyle: teeth too big for a head that is already too big for the body. A nightmarish, malevolent little hobgoblin. He leers down at his delightedly shuddering audience with that horrid grin. “Max Wall, ladies and gentlemen, standing before you . . .”

Some facial contortions, followed by the immortal Professor Wallofski’s funny walk.

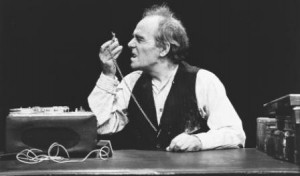

After the success of Cockie! in 1973 – Max basically did his old music hall act, privately describing it to me as “just more of the same old crap” – he was back on top again, hailed as “a genius” and the pet of intellectuals and the chattering classes. He became a superb straight actor, bringing 50 years of comic technique, and intimate knowledge of life’s vagaries and cruelties, to roles in works by Shakespeare, Wesker, Pinter and, especially, Samuel Beckett, where he scored tremendous triumphs in Waiting for Godot and Krapp’s Last Tape, becoming acknowledged as a major interpreter of the Irish playwright’s work. It is easy to see why. Both mined deep seams of bleakness, humour, futility, hope, hopelessness. And Max Wall’s delivery perfectly suited Beckett.

Professor Wallofski: “Where’s the piano stool? I want a stoooool. A stoooool. For my botty.”

Krapp: “A spoooool. A spoooool.”

“There are an awful lot of pauses in this play, Mr Beckett,” he said mischievously to the playwright, who had dropped into a dress rehearsal for Godot. “Do you mind if I do one of my funny walks?”

Beckett just smiled. They would have understood each other very well.

IN 1974 I chatted to Max in his dressing-room at the Greenwich theatre where he was playing Archie Rice in John Osborne’s The Entertainer, directed by the author. Osborne wryly told me Max was subverting the play because he couldn’t resist building on laughs where Archie was supposed to be dying on stage, but he didn’t seem to mind too much. Years later he wrote: ‘There was little I could do to improve on the way he melted and insinuated himself into the part. With his skill as a dancer came the gift of withholding, conjuring unimaginable surprise. He never made the smallest movement that was not felicitous and fastidious, whatever the comic outcome, whether it was opening a bottle of Dubonnet or leaning on his cane like a reflective, startled ape, peering out through the bars of his remote cage. . . . The effect was superb and almost ruined the characterisation. Archie Rice was not supposed to be funny, nor an ornament of the times.’ (5)

Writing in The Guardian in August 2016 to mark Kenneth Branagh’s new production of The Entertainer, Simon Callow recalled Max’s Archie and got it just about right:

‘Only one British actor in living memory has effaced the imprint of Olivier, and that was the great comedian (and novelty dancer) Max Wall, who played Archie in Osborne’s own perhaps over-loving 1974 revival at Greenwich theatre (it lasted nearly four hours).

‘As if in negative image, Wall reversed Olivier’s conception. In the front cloth scenes, Olivier showed a tenth-rate performer who, despite a lack of talent, was eager to make an impact. In the private scenes, he exposed the man’s despair; when he showed Jean his dead eyes, they were in fact shot through with excruciating pain. When Wall played the same scene, his eyes were unnervingly dead; during the scenes in the music hall, he presented Archie as effortlessly skillful but deeply bored, just sketching it in.

‘He nonchalantly knocked off a few steps, full of contempt for his audience, whereas Olivier put everything he had into the dancing. Wall’s performance revealed the full-blown romanticism of Olivier’s approach: he drew a tragi-comic portrait of a soul in hell. Wall’s Archie was flatly realistic, and all the more disturbing for that. The man was a dead cinder. The performance made the play seem smaller, less epic, but in some ways better, more real, less schematic. It was less entertaining and more disturbing.’ (8)

‘He nonchalantly knocked off a few steps, full of contempt for his audience, whereas Olivier put everything he had into the dancing. Wall’s performance revealed the full-blown romanticism of Olivier’s approach: he drew a tragi-comic portrait of a soul in hell. Wall’s Archie was flatly realistic, and all the more disturbing for that. The man was a dead cinder. The performance made the play seem smaller, less epic, but in some ways better, more real, less schematic. It was less entertaining and more disturbing.’ (8)

Work was what kept Max going, and only onstage, in a TV studio or on a movie set did he find a measure of contentment. Of all the bizarre, indiscreet, embarrassing, self-hating comments this strange, gifted and deeply-unhappy man made over the years, I think the following is perhaps the most heartbreaking, from an interview he gave to Woman magazine in 1975: “I’ll tell you what I dream of. I dream of owning a little cottage, an olde-worlde one. It’s in the heart of the country. Or, better still, it’s by the sea. There are lots of oak beams and crimson curtains. It’s very cosy and homely . . .”

He didn’t say if he imagined another person there to share his impossible dream.

Let’s try and leave Max on as high a note as we can manage. My favourite quote about him comes from American author John Lahr, son of Oz’s Cowardly Lion Bert Lahr, another comic who became a great interpreter of Beckett in his old age. “He was an isolated, sullen, feisty man who brought his sadness on stage and dumped the hostility that came with it hilariously in the audience’s lap,” he wrote in his book Light Fantastic. “In his sorrowful caperings, Max Wall took the audience where only a great clown can: to the frontiers of the marvelous.” (6)

Walk on, Max . . .

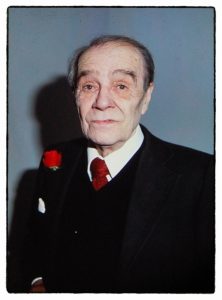

TO his bemusement, considering the way he’d been treated during the previous twenty years, the sad little man ended his days as something of a National Treasure. Maybe it was appropriate, considering he’d been buried for years and then dug up again. He was relieved to be out of debt, back in demand and with a few quid in the bank, naturally, but he wasn’t impressed by the accolades. It had all come a bit too late. Away from the cameras and stage lights he lived as a near-recluse in a little council flat, snubbing colleagues and well-wishers, and occasionally venturing out to the local pub, where he invariably sat alone drinking Guinness. A neighbour said: “He’s rarely seen. He seems to spend much of the day sleeping.”

Liz Smith, who co-starred with Max in one of his last films, We Think the World of You, said: “It’s very

Liz Smith, who co-starred with Max in one of his last films, We Think the World of You, said: “It’s very

sad. He’s a legend. Yet at the end of such a long career he seems to have lost so much. It would be nice for him to be surrounded by warmth and affection.” (7)

On May 21st, 1990, Max Wall, 82, was entertaining two friends, fellow-diners and the staff over a boozy four-hour lunch at his favourite London restaurant, Simpson’s in The Strand. As he left the building he lost his footing on the stairs and fell heavily. He died the next day in hospital without regaining consciousness. An inquest recorded a verdict of accidental death. He had fractured his skull but wouldn’t have lived much longer anyway – the inquest disclosed that he had a brain tumour and severe heart disease.

The comedian who had spent so many years broke or bankrupt left £193,000 in his will. The money went to four of his children, seven grandchildren and charity. His eldest son, Michael, was specifically excluded.

Here’s a last laugh from Max – his brilliant version of Ian Dury’s song England’s Glory, recorded in 1977.

All text Copyright Stephen Dixon 2013. All illustrations, except where specified, from Stephen Dixon Collection, acquired from various sources over a 40-year period and in many cases provided by the artists themselves in the 1970s. If anyone has copyright or permission issues, please contact me.

Other text sources

(1) Interview in Penthouse, 1974, Vol 9 no 3.

(2) The Fool on the Hill, by Max Wall. Quartet Books, 1975.

(3) The Sun, May 23, 1990.

(4) Roy Hudd’s Book of Variety, Music Hall and Showbiz Anecdotes. Robson Books, 1993.

(5) Independent on Sunday, May 27, 1996.

(6) Bloomsbury Books, 1996.

(7) The People, October 1, 1989.

(8) The Guardian, August 13, 2016.

stephendee

| #

Doesn’t ring a bell with me, Stefan, tho it’s a very typical Sarony line. Anyone? Stephen

stefan Beard

| #

Just been reading the Leslie Sarony piece. Absolutely fantastic. Well done. A question if you don’t mind. Does anyone know the the title of the Leslie Sarony song that has the line “Oi ! how you gettin’ on? ” in it ?

ruskimic

| #

I do hope you can help me. I have been searching for many years for my Great Uncle Mr Albert Edward Rayner who went under the name of Dan Rayner. I believe he worked the Music Halls but I do know for sure he worked with Fred Karno. When Charlie Chaplin left Fred in America over a Pay dispute the American backers of the tour insisted that my Great Uncle Dan Rayner be called over from England to take Charlie Chaplin’s Place. It appears Dan was liked more at that time in America than Charlie was. Another man in the troupe at that time was Stan Laurel. When the show folded Dan was asked along with Stan to stay in America. As we know Stan stayed and found he fame and fortune. Dan however chose to return to England. He was last that I can find in a play Dick Wittington at the Empire Theatre advertised in the a local paper in Durham in 1948. Unfortunately I have not been able to find when or where he died. I am hoping that maybe on your search you came across some info on Dan Rayner. I live in Australia so am unable to search all the death records for England with out it costing me a fortune. So any help you maybe able to give me would be really appreciated. I know he went to America twice and once to Australia and also once to South Africa. I do know he was married to a lady named Barbara Robinson and they had a son Conrad Paul Rayner but I have been unable to find any thing out about these two members of his family. I do know they separated before 1935 and he lived with another lady named Phyliss but as to her last name I have no idea. I have been searching for nearly 10 yrs now and I don’t think there is any thing left on the net that can help me. You it would appear maybe my last chance. I will keep my fingers crossed that you did come across some info on him or you know some one that maybe able to help. He went to America in 1913 on the Lusitania and it shows at this time he is married. He then returns to America in 1914 on the ship Adriatic. I do believe he also did a radio show after 1935 for quite some time but do not know the name of that show. I do hope you can help in my search for my Great Uncle.

I also might add my great grandfather was Edwin Richard Barwick. He was also a Music Hall performer and appeared in the first Royal Command Performance. If you get the picture and Index to that even you will see him standing next to Pavlova. I would love to hear any information you may have found out about him. I do believe he was one of the first members of the charity named water rats, I know star was spelt back wards to get the rats part. Edwin did a lot of work for this charity in his day. What I would love to know is if there is any recording of Edwin Performing and if so how I would go about getting a copy or seeing any recording. I do have a photo copy of an old theatre bill with my grandfathers name boldly written on it. Again any help would be appreciated.

All the best and I look forward to hearing back from you in the near future

Kim Rayner

my email address is ruskimic@yahoo.com.au