Don Ross and ‘Thanks for the Memory’

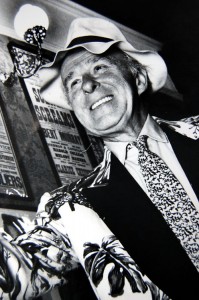

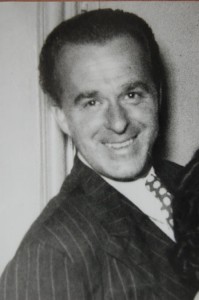

HE was a tall, tanned, silver-haired man, strikingly handsome in his mid-seventies, and he still had the grace of the acrobatic dancer he had been fifty years before, plus the instinctive comic timing of the old pro. We talked at his elegant apartment at Hove, near Brighton, and after offering me a sherry, he accidentally snapped the stem of the expensive-looking glass as he was pouring. Looking from the broken glass to the sherry bottle, then to me, repeating the routine for maximum effect, he pursed his lips wryly: “I think the phrase is ‘oh shit’,” he said.

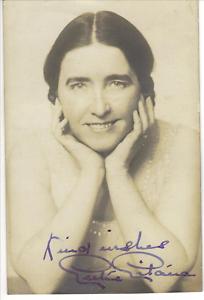

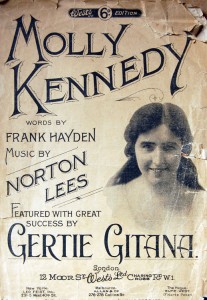

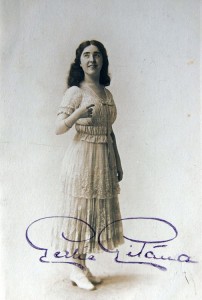

Don Ross was the real thing: a man completely steeped in music hall. He had known many of the great performers as friends, hired several of them in shows he produced, acted as agent for others, and had been married to the legendary singer Gertie Gitana, billed as The Star Who Never Fails to Shine, who made her debut at the age of four in 1892 and went on to immortalise the ballad Nellie Dean.

Don Ross was the real thing: a man completely steeped in music hall. He had known many of the great performers as friends, hired several of them in shows he produced, acted as agent for others, and had been married to the legendary singer Gertie Gitana, billed as The Star Who Never Fails to Shine, who made her debut at the age of four in 1892 and went on to immortalise the ballad Nellie Dean.

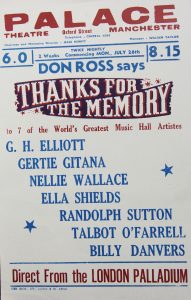

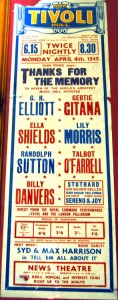

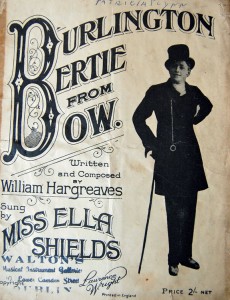

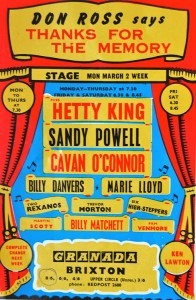

Ostensibly I was there to discuss Ella Shields for a centenary piece on the Burlington Bertie male impersonator The Guardian had commissioned. Ross had employed Shields – plus Nellie Wallace, Hetty King, Lily Morris, G.H. Elliott, Randolph Sutton, Talbot O’Farrell and many others.

And talking about Ella Shields meant talking about his famous show Thanks for the Memory. As he gently reminisced, sherry in hand, a story began to unfold, a story of great love and intolerable loss; of laughter and tragedy; of fading stars regaining their lustre to bask in the limelight one last time; of loyalty and rivalry; geriatric crankiness and warm camaraderie . . . an American woman who pretended to be a man, a white man from Lancashire who pretended to be an Afro-American, an Englishman named Parrot who pretended to be Irish. Magic and illusion, smoke and mirrors . . .

AT the end of the century before last, Stoke-on-Trent was at the heart of the British ceramics industry, and Gertrude Mary Astbury, who was to become Gertie Gitana, was born in the Longport area of the town in 1887. Her father laboured in the giant kilns of the pottery factories as a lowly saggar-maker’s bottom-knocker, though he later rose to management status, and when his tiny daughter was spotted singing in the street by someone from the local Tompkinson’s Royal Gypsy Children’s Troupe, economic circumstances dictated that he agree to let the infant join the company. Billed as Little Gitana – gitana being the Spanish for female gypsy – Gertie was touring Britain by the age of eight.

So precocious was her talent that some audiences refused to believe she was a child, and she was on occasion outrageously billed as:

England’s Premier Midget Comedienne

Wonderful Little Gitana

The Unapproachable Liliputian Song and Dance Artiste.

Tyrolean Yodeller, Male Impersonator and Paper Tearer

A skilled saxophonist and step-dancer, she became a massive star on the halls and in pantomime and was associated with many hit songs, including Silver Bell, with its intricate yodeling intro, the plaintively resigned Never Mind and, of course, Nellie Dean.

There’s an old mill by the stream,Nellie Dean.

Where we used to sit and dream,

Nellie Dean.

And the waters as they flow

Seem to murmur soft and low.

You’re my heart’s desire.

I love you,

Nellie Dean.

While Nellie Dean seems a song that should rightly be sung by a man, in Gertie’s rendition a young girl recalls idyllic trysts, and the endearments whispered by the boy she loves. By the time she was 15 she was getting £100 a week, more than her father had ever earned in a year. And she had become a steely and audacious pro. There is a famous showbiz story about Gertie playing Cinderella in panto. When everyone has gone to the ball she sits in her rags weeping in the kitchen, then brightens and exclaims: “Here I sit, all alone – I think I’ll play my saxophone!’ Reaching up into the chimney she produces the instrument and goes into her standard music hall act. (This apocryphal tale – Don Ross always smilingly refused to confirm or deny it – is matched by the later one about variety comedian Issy Bonn, playing the Genie in another panto, saying to Aladdin: “I can grant you three wishes. What is the first?” to which the lad was obliged to reply, probably through gritted teeth: “I’d like to hear Issy Bonn singing My Yiddisher Mama.”)

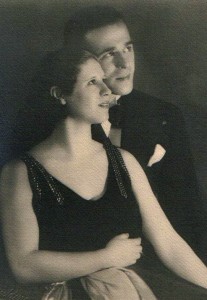

DON Ross was born into the middle classes near Leicester in 1902, and though his father wanted him to try journalism or stock-broking, the boy was stage-struck and left home in his late teens to join Papa Cragg’s Gentlemen Acrobats, leaving to tour as a solo act once he had learned to dance. In the 1920s, as fashions changed, Gertie Gitana had switched to revue in a series of successful shows, and in 1926 she auditioned Ross for the leading role of Billy Rodgers in Dear Louise. He got the part, they became lovers in spite of a 15-year age gap, and were married in the following year. Gertie always called Don ‘Bill’ or ‘Billy’ because of his role in Dear Louise, and so did most close friends and colleagues.

After Louise, Ross went on the halls in a dancing act with his partner Joy Dean, often on bills topped by his wife, who had returned to touring in variety. An astute businessman, in the early 1930s he took over the management of Gertie’s career and teamed her with G.H. Elliott in a successful revue called George, Gertie and Ted (a very young Ted Ray) which toured for four-and-a-half years. Gertie and Don spent 1935 in the United States, and when war broke out in 1939 Don passed his medical for the army but his work providing morale-boosting entertainment was considered a reserved occupation, and he was not required to fight.

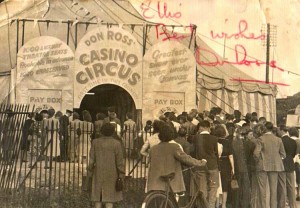

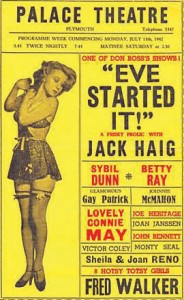

Throughout the war he toured a theatrical version of traditional circus around the halls, and was also the first producer to bring striptease to the British stage. Eve Started It! in 1942 was described on posters as ‘a frisky frolic’ promising ‘8 Hotsy Totsy Girls!’

Gertie, meanwhile, had retired. She was quite wealthy, had worked hard since the age of four, and did not want to appear on stage in her fifties. Then her husband came up with the idea for Thanks for the Memory in 1947. . .

Don Ross was not the first producer to revive music hall entertainment. Stalwarts of the halls from the 1890s such as George Robey, Gus Elen, Marie Kendall, Harry Bedford, Kate Carney and Harry Champion had been starring in nostalgia shows from around 1930 onwards. Nor was he the last – when he stepped back from Thanks for the Memory he passed on the baton to Chesney Allen, Don Ellis, Audrey Lipton, Arthur Lane and others who continued to tour Old Time Music Hall shows until the end of the 1970s, ceasing only when the last of the old stars died or became too infirm to perform.

Here’s one of the great old performers who made a comeback in the early 1930s in music hall revival shows: Gus Elen.

And another was Marie Kendall, here singing her great hit Just Like the Ivy.

But Ross was, quite simply, the best, and Thanks for the Memory is regarded as the finest of its kind, playing to rapturous publicity and capacity audiences during its touring years and featuring to great acclaim in the 1948 Royal Variety Performance alongside Julie Andrews and Danny Kaye. Much of Thanks for the Memory’s appeal lay in the way he structured the show. Rather than being a self-indulgent nostalgia-wallow, it was a fast-moving, zippy production featuring many younger supporting artists, and the old stars were mostly required to go on, do their stuff as briskly as possible, and get off, appearing together only in the glittering finale. And the main reason for the show’s success was an extraordinary chemistry that sparked between the performers, some of whom had been friends for decades.

GERTIE Gitana was prepared – even eager – to emerge from retirement to support her husband’s project, and Ross began to cast around for the rest of the company, each star representing some different facet of music hall. First he approached the great comedians Nellie Wallace and Lily Morris. But it turned out that they disliked each other and were not prepared to be on the same bill, and, anyway, Morris was fully retired and Wallace, busy nursing her only daughter, who was extremely ill, was concerned about the show’s age profile – “bath chairs at the stage door and all that” – even though she was herself in her seventies.

Next he tried to hire a male impersonator. Hetty King’s unacceptable demands had ruled her out of the show, so Ross began to make enquiries about Ella Shields, the great Burlington Bertie, who had not been seen in Britain for several years. Shields was one of the most enchanting artists to emerge from the halls; a chuckling, warm, American-accented performer who, unlike Vesta Tilley or Hetty King, never expected audiences to believe she was actually a man. She was just charmingly herself, dressed in male attire but at the same time wholly feminine.

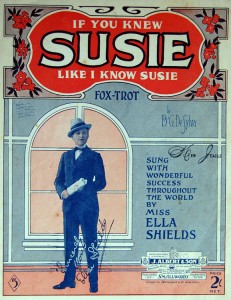

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1879, she toured the States as a singer and made her British debut at Forester’s Music Hall in London in 1904. After success in pantomime, she first appeared as a male impersonator at the London Palladium. She had many famous songs in her repertoire – Adeline, Show Me the Way to Go Home, I’m Not All There, Cecilia and If You Knew Susie – but her best was, of course, the imperishable Burlington Bertie from Bow, written in 1914 by her then-husband (she later divorced him for cruelty) William Hargreaves as a parody of a successful Vesta Tilley song.

Ross happened to bump into Georgie Wood (a midget performer who had a famous act in which he impersonated a little boy, assisted by his stage ‘mother’ Dolly Harmer) on Tottenham Court Road and asked him about Ella Shields. All Ross knew was that she had gone back to America at the beginning of the war.

Wood turned out to be a friend of Ella’s, and it was a sad story he had to tell. She’d had a hard time in America and was pretty broke; she’d been reduced to working in bars and honky-tonks and for a time even served behind the costume jewelry counter at Macy’s store in New York.

Then, said Georgie, she got a break of sorts and was currently working in New Zealand in some kind of big touring tent show. Ross contacted her and she cabled back that she’d be delighted to join Thanks for the Memory.

Even though she had sabotaged her own chances of appearing in the show, Hetty King was nonetheless enraged by the inclusion of Shields, whom she quite unreasonably detested and resented. “Hetty was always very spiteful about Ella,” said Ross. “She once did a press interview and the reporter said to her: ‘There were three famous male impersonators, were there not?’ and Hetty said: ‘Three? Three? Well, there was Tilley. And myself. But three? Oh,’ she said as fake realisation dawned, ‘you must mean that Little Miss Shields’.”

Here’s a clip of Ella Shields singing one of her big hits, Adeline.

ROSS then got in touch with his old friend G.H. Elliott, who was on holiday in Switzerland, and, after some prevarication – Elliott laboured under the amusing delusion that he was about to crack the youth market and, like Nellie Wallace, was reluctant to be identified with an old-timers’ show – the Chocolate Coloured Coon agreed to come aboard. Perhaps at this stage we should make a slight digression to examine the phenomenon of the music hall ‘coon’. Today the notion of a white man from Rochdale blacking-up and dancing around the stage singing about Carolina plantation fields and ‘palpitating n*****s’ (Lily of Laguna) is both ludicrous and deeply offensive. In the unlikely event of anyone trying it now, they could possibly be prosecuted under the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006.

But in G.H. Elliott’s heyday it was part of a tradition of racial stereotyping – the lazy or happy-go-lucky darkie, rarely sinister – that went back to the minstrel shows of the 1830s and is an important part of American theatrical history, whether we like it or not. Jewish performers such as Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, whose families had fled to America to escape poverty and discrimination, began their vaudeville careers in blackface (examples of one persecuted minority impersonating another) and few turned a hair when Fred Astaire, Bing Crosby and even Shirley Temple appeared on film blacked-up. It all-but-vanished as a quantum in British entertainment with the demise of The Black and White Minstrel Show in 1978, though blackface characters have appeared on TV’s Little Britain and The League of Gentlemen in recent years, now safely cloaked in the smirking irony that permits material considered unacceptable.

George Elliott was born in Rochdale in 1884 and shortly afterwards his parents moved to America. He made his stage debut playing Little Lord Fauntleroy in New Jersey and at the age of nine joined a minstrel troupe as a singer and dancer. He moved back to Britain in 1902 and, after the death of Eugene Stratton (the original singer of Lily of Laguna) in 1918, Elliott became the foremost ‘coon’ artist in Britain.

From talking to his widow, June Franey, and friends and colleagues of his, it seems that Elliott was not really a racist in today’s sense of the term. He was certainly ignorant about the real lives of people of colour, or, indeed, much else outside the make-believe world of theatre. But, then again, racism has its roots in ignorance, doesn’t it? There were very few black faces on the streets of Britain during the great days of the music halls, and Elliott’s white-suited, dandified ‘coon’ was a romanticised fantasy figure with no links to any reality. “Old George was only about fifty at the time [he was actually 64] but he seemed much older,” said Thanks for the Memory accordionist and dancer Terry Doogan. “I wouldn’t say he was naïve, but he wasn’t a worldly gentleman, really. George just lived for his act – it was the only thing in his life, really.”

Here is the only known clip of G.H. Elliott, singing one of his big hits, Sue Sue Sue in the movie Music Hall (1934), directed by John Baxter. Racial issues and cultural appropriation aside, his stagecraft is impeccable and his charm immense. It is easy to see why audiences loved him.

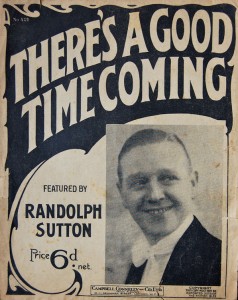

NEXT, Ross contacted Randolph Sutton. Born in Bristol in 1888, he had been billed for thirty years as Britain’s Premier Light Comedian. Sutton, a performer of tremendously twinkling charm and cheekiness, always immaculate in top hat, white tie and tails, could be described as a kind of sophisticated George Formby, delivering a similar type of innuendo-laden song but in an endearing West Country burr that made them seem less thuddingly-smutty. The lyrics to some of his songs left little to the imagination; You Ought to Know Better, a Big Girl Like You has a mother advising her daughter:

Just lead him up the garden but don’t let him pick the flowers.

Remember what your mother said,

And keep him off the parsley bed.

You ought to know better, a big girl like you!

He inherited his most famous number, the sentimental On Mother Kelly’s Doorstep, from early music hall star Fred Barnes, and when Sutton was gone Danny La Rue made it his own, the song thus passing through three generations of gay entertainer.

Although Sutton lived with Terry Doogan for more than 30 years, he had been married, to Nellie, and fathered a son, John, who went on to become a musician and made several records as ‘Randolph Sutton Jr.’ John also had a son, John Randolph Sutton, who was active in show business as a singer, comedian, cruise entertainer and agent until his death in 2016. In fact John Randolph Sutton and I were Facebook friends! Judging from photographs I have seen, Ran, Nellie and Terry seem to have got on famously, and all three sometimes attended public events together.

Terry Doogan: “Randolph Sutton had retired after doing a week at Chiswick with Henry Hall and His Band. The audiences weren’t very good and he was disappointed, so he retired. He didn’t work for about eight months. Then Don rang around various people that he wanted, including Ran, and Ran said he was interested in it and asked who else was involved. Don told him who he’d got and Ran said okay but ‘the boy’ – that’s me – had to be with him, because I looked after him. So Don said: ‘I’ll arrange for him to do an act with some girls.’ Ran said: ‘I’ll give you four weeks, then, and if I’m not happy then will you release me?’ Of course, after the four weeks it was obvious that it was a much bigger success than anyone thought it was going to be, and Ran stayed with the show for the entire run.”

Here’s Sutton with one of his sauciest . . .

SUTTON also proved to be instrumental in getting Nellie Wallace to change her mind about Thanks for the Memory. Doogan: “Nellie was going through a bad time with her daughter, who was dying of cancer, but Norah, the daughter, thought it was a good idea for her to go into the show, so Nellie rang up Don and asked: ‘Who else have you got?’ and she agreed to be in it when Don told her Ran was involved, because Ran and Nellie were very good pals.”

An extremely odd person offstage as well as on, Wallace, born in Glasgow in 1870, was music hall’s most beloved female grotesque comedian. Known as The Essence of Eccentricity, sometimes The Quintessence of Quaintness, she had buck teeth and a huge, beaky nose and her skinniness was heightened by a little hat with one tall, quivering feather. She wore big boots and a tatty fur stole she called her “little bit of vermin,” and had been a top star since 1910 with her surreal patter and bizarre songs such as Three Times a Day, The Blasted Oak and Let’s Have A Tiddly at the Milk Bar, and Under the Bed, one of her best:

My mother said: ‘Always look under the bed.

Before you put the candle out, see if there’s a man about.’

I always do. But you can make a bet

That I’ve never had the luck to find a man there yet!

Here’s Nellie with one of her great favourites:

DON Ross also hired singer Talbot O’Farrell and comedian Billy Danvers. O’Farrell was billed as The Greatest Irish Entertainer of All Time but he was, you will be unsurprised to learn, nothing of the kind. Born William Parrot in the north of England in 1878, he first went on the halls as Jock McIvor, Scottish Comedian and Vocalist. Jock didn’t catch on, so he switched to an Irish impersonation and never looked back. O’Farrell’s Irishman, in frock coat, check trousers, white gloves, spats and grey top hat, was about as convincing as Elliott’s negro or Shields’s man; O’Farrell didn’t try for a brogue, for example, and did his act in his natural Northern accent. His songs were lachrymose – How Ireland Was Made, That Old-Fashioned Mother of Mine, The Lisp of A Baby’s Prayer – and by the late 1940s his voice had deteriorated into a quavering bawl, but O’Farrell was still a canny choice on Ross’s part because he was also a fine comedian, his relaxed patter between songs clever and appealing, and audiences adored the old fraud.

To see Talbot O’Farrell with typical patter and a sentimental Irish ballad, click here.

Billy Danvers, billed as Always Merry and Bright or Cheery and Chubby, was an unpretentious, old-style, red-nosed, front-of-tabs comic. Born William Mikado Danvers in Liverpool in 1884 – his father was appearing in Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas at the time – he provided an element of robust gaggery that perfectly balanced out the whole Thanks for the Memory package.

Each of the seven stars was on a straight salary of £100 a week.

REHEARSALS for the show began, though Nellie Wallace was absent for many of them because of the gravity of her daughter’s illness. She would appear from time to time, however, rushing into the theatre shouting: “Don’t speak to me! I don’t want anybody to speak to me!” During these unpredictable attendances she would sometimes wander around backstage squirting a disinfectant spray-gun into nooks and crannies, muttering: “Dirty beasts! Filthy beasts!”

Ella Shields was much easier to deal with. Ross: “She arrived for rehearsals bubbling over with ideas and innovations. She wanted the girls on the stage dressed as costers while she sang Burlington Bertie from Bow, plus a coffee stall. So we decked the assistant stage manager as a coffee stall attendant and built the stall. Then on the first night she decided she’d do it without the girls. Then she changed her mind about the stall. But we didn’t mind. We loved her. Too many people who do Burlington Bertie nowadays wear immaculate evening clothes. All wrong. Ella wore a slightly shabby dinner jacket, a topper that was just a little dull and dented and gloves that were almost threadbare. She judged it so carefully. Not a swell. Not a tramp. Just a rather philosophical fellow a little on his uppers.”

Doogan: “The girls and I were having a break and sitting on the floor of the stage and in came this lady in a black and white costume and a nice little hat and a short haircut. And she came over to us and in that lovely American accent she said: ‘Oh, I believe you’re Terry. I’m Miss Shields, and Mr Ross says you’re going to be doing something for me before I go into Burlington Bertie.’ I’ll always remember her walking onto the stage of that theatre, in this little costume that looked as if it didn’t belong to her and which, we discovered later, she’d borrowed from her daughter to come over in, because Ella wasn’t very flush at the time. Ran thought Ella was a superb artist – beautiful. And as a person he loved her. Onstage she was like Ran, in a way. You see, Ran would take a song, or a picture number, like his circus or his dog songs, and he could turn it into something where people would imagine they were at the circus, or they could see the little dog, and Ella could do that in the same way with her numbers.”

Ross: “Ella was a bit sloppy. She never bothered much about clothes. When she came back from New Zealand she came off the boat and she looked just like a little housewife, chatting to other housewives. Offstage her figure was rather dumpy: she had very wide hips and was bit pear-shaped. Onstage she managed to hide this by the way her jackets were cut, and she always looked elegant. She didn’t bother about her make-up too much. She used to tuck a paper napkin into her collar to stop it getting on her shirt and quite often she’d go onstage with it still tucked in and at the beginning of her first number it would fly up over her face. She’d just laugh it off because she had tremendous confidence onstage.”

Less so off, however. Sometimes she would say to Ross: “I’m a great artist. And a great woman. I am, Bill, aren’t I? Aren’t I?”

“Ella was basically a very lonely person,” said Doogan, “because apart from being very reserved she didn’t have a lot of money. Also, in Thanks you had Gertie, who was married to Don, so that was a twosome; you had Billy Danvers and his wife, who traveled with him; there was Talbot O’Farrell and his pianist, who was always with him, and his wife used to come up quite a lot when we were on tour; there was June and George; and, of course, Ran and I were together. Nellie was away a lot looking after her daughter. So Ella was the odd one out on her own, so that’s why at times she felt a little lonely.

“As far as I can remember, from seeing it in her ration book – because I often used to go and get her ration slips for her – Ella had a husband named Buck. But as far as I know nobody ever saw him. Minnie Goss, who was Ella’s dresser, and had been with Ella for years, right since before the war, said she married this man Buck on a boat either going to or coming back from America, and that was all there was to it. They never saw each other again. It must have been a kind of shipboard romance.”

Ross: “He was, according to Ella, a cowboy of Adonis appearance and fantastic physique, and much younger than her. Whenever she spoke of Buck she turned her eyes up to heaven and said: ‘Oh, my dear!’”

“There was no problem over billing in Thanks for the Memory,” said Doogan, “because George Elliott, who was a darling man, and loved by everybody in the business, always insisted that he should be First Top and so everybody agreed. They all had the same size billing, so it wasn’t like being First Top really. Everybody in the profession loved George, and all the stars in Thanks for the Memory said ‘Well, let George be Top’ and they also let him have the Number One dressing room, because that was George’s life, and if he’d have thought that he was going to be Second or Third Top, in Number Four or Number Five dressing room, he would have been just broken up. So everybody gave way to him.”

THE first night at the Empire Theatre, Brixton, in February 1948, was an unqualified triumph, with fans besieging the stage door and The Performer newspaper commenting: ‘One of the greatest music hall happenings for a generation. Seldom if ever in its long and colourful history has the Empress witnessed such stirring scenes as those which greeted the premiere of Don Ross’s Thanks for the Memory.’

Ross played me his own private recording – on vast, breakable 78rpm discs – and there is also in existence on CD a BBC radio broadcast that was made of the show, so it is still possible to savour the atmosphere of Thanks. After tenor Paul Conrad sang the theme song, which had been popularised by Bob Hope and Shirley Ross in the movie Big Broadcast of 1938, a dancing act, The Six Silver Bells and Terry Doogan, set the scene, followed by an acrobats Marguerite and Charles.

Then Randolph Sutton skipped on to deliver one of his sauciest numbers, My Girl’s Mother, which was fairly unequivocally about a man having affairs with both a young girl and her mother:

My girl’s mother, my girl’s mother.

Though she’s over forty,

Still, she’s very sporty . . .

Who says ‘Now, Maisie, you go up to bed

And come here on the sofa and cuddle me instead?’

My girl’s mother, my girl’s mother,

She’s more than a mother to me.

Sutton closed with On Mother Kelly’s Doorstep, charming the audience into singing along simply by cupping a hand to his ear and smiling encouragingly.

Nellie Wallace followed, introduced in voice-over: “A funny hat . . . a long feather . . . a bit of skunk . . . a little muff. Who could it be but – Nellie Wallace!” Her act was both extraordinarily lugubrious and exceedingly funny as she squawked dementedly away about death and suicide, and began with one of her best-known songs, which was about pies:

I can’t stand my mother’s pie-crust.

Eat it? I would sooner die first!

I’ll tie it round me neck, and tomorrow I will be

Down at the bottom of the deep blue sea.

She then told a cheery little story about the death of her father: “My poor, dear father. I can see him now, just before he died. He said: ‘Can you see me, my pretty one?’ [laughter] . . . the doctors wanted us to take him to the seaside. But we couldn’t afford it. We had no money! So what did I do, his noble daughter? I sat by his bedside and fanned him with a kipper.”

Another chorus of Mother’s Pie Crust and then it was: “That ideal of ideals, the evergreen Burlington Bertie – Ella Shields!” She sang chucklingly of young love in Cecilia and then went into I’m Not All There, a rather uncomfortable talk-song about someone who can get away with all kinds of bad behaviour because he encourages others to suppose he is mentally subnormal. It would be unthinkable that her last number would be anything other than:

I’m Bert. P’raps you’ve heard of me.

Bert. You’ve had word of me,

Jogging along, happy and strong, living on plates of fresh air.

I dress up in fashion and when I am feeling depressed

I shake from my cuff all the whiskers and fluff,

I’m Burlington Bertie, I rise at ten-thirty,

And saunter along like a toff.

I stroll down The Strand with my gloves on my hand

Then I stroll down again with them off.

I’m all airs and graces; correct, easy paces;

So long without food I forgot where my face is . . .

I’m Bert, Bert, I haven’t a shirt,

But my people are well-off, you know.

Nearly everyone knows me,

From Smith to Lord Roseb’ry.

I’m Burlington Bertie from Bow.

Here she is singing Burlington Bertie from Bow in a clip from a filler presumably intended for cinemas in the 1930s. The picture quality isn’t great – but at least this record of her singing her greatest song survives.

Talbot O’Farrell closed the first half with his bogus paddywhackery and excruciating songs, and the second half opened with more dancing from Terry and the girls. Then on tripped Gertie Gitana, looking nothing like her sixty-one years by all accounts, though the voice was little trembly. She sang Silver Bell, accompanied by a small male chorus and topped and tailed by her trademark yodeling, then performed a medley of her old songs, closing, of course, with Nellie Dean.

Fruity-voiced Billy Danvers was on next, describing himself as “the youngest veteran in captivity.” After a quick song he went into his patter. One of his best gags – used not here but in subsequent Thanks for the Memory productions – went: “Three men were stood in a pub having a drink, you know, all boasting about their wives – it’s very seldom you’ll hear a man boasting about his wife, especially when she’s not there. One said: ‘My wife has the most beautiful eyes in the world; they’re pale blue.’ The other said: ‘That’s nothing. My wife’s got lovely eyes as well. They’re grey eyes.’ So they turned to the third man and said: ‘Tom, what’s the colour of your wife’s eyes?’ And he said: ‘I don’t know. I’ve not noticed. I should have done. I’ve been married long enough.’

“And it worried him. So he went home but he couldn’t find her in the slavery – the kitchen – so he went into the lounge and there she was sat on the settee in her dressing-gown, reading, so he went straight up to her, looked right into her face and said: ‘Brown!’ And a feller got up from behind the settee and said: ‘How did you know I was here?’”

G.H. Elliott closed the show with I’m Going Back Again to Old Nebraska and Lily of Laguna, featuring his distinctive and beautiful dancing, described by one observer as: ‘He drifted around the stage like thistledown.’ As the audience sang along at the end of Laguna, Elliott used their chorus to riff against in counterpoint. Only one movie clip of Elliott seems to exist, performing another of his numbers, Sue Sue Sue, and while the racial condescension of his portrayal jars, the overwhelming charm and total command of the audience is obvious.

For the finale there was a platform at the back of the stage with a long table covered in flowers and bottles of champagne. As it slowly moved to front stage the seven veterans sitting or standing around it toasted each other and the audience, laughing and blowing kisses. Thanks for the Memory was 1848’s biggest stage success, touring Britain to packed houses, playing for a fortnight at the London Palladium and featuring in that year’s Royal Variety Performance.

WITH such an elderly cast, it was inevitable that Thanks for the Memory would be beset by health problems as it trundled around the country. Nellie Wallace was sometimes absent as her health went downhill along with that of her daughter, her place on the bill taken by Renee Houston and Donald Stuart, and Talbot O’Farrell was a diabetic and had gangrene. In spite of his lifetime in the business, and his relaxed and confident act, Randolph Sutton suffered badly from stage fright, and also had sciatica. Doogan: “On the first tour, at the Empire, Newcastle, on the Wednesday second house, Ran stooped down to the footlights and then found that he couldn’t get up again. So he finished the chorus and the tabs closed but he couldn’t take a bow because he couldn’t get up. So I dashed on with the stage manager, and we got him off the stage. His back had locked and he couldn’t finish the week.”

Personality clashes were also inevitable. Doogan again: “When Ella had been with Thanks for about 12 months, and she had got a bit of money behind her, she got all her jewelry out of hock in America. She got some friends of hers who were going over there to get her jewels and a couple of fur coats. They took the tickets and got them out. One of Ella’s great delights, during the second year of Thanks, in the four-week break, was going back to America in all her furs and jewelry and deliberately snubbing all the people who treated her badly when she was a little bit down and out.

“On the first occasion people had to share dressing rooms, Ella was sharing with Nellie Wallace and in between shows I went into the prop room for some reason and there was Ella, sitting on some old discarded prop from panto. A king’s throne, I think it was. And she’s sitting there reading a newspaper. So I said: ‘What are you doing here, Ella?’ And she said: ‘I cannot stand that woman’s language a minute more.’

“Nellie was very down-to-earth. She was a darling, but she was a very awkward woman to get on with, though Ran and I understood her. I said: ‘What are you talking about, Ella?’ And she said: ‘Nellie, upstairs. Her language is terrible and I can’t stand it.’

“So I went upstairs and into our dressing room and I said to Ran: ‘Poor Ella’s sitting in the props room because she can’t stand Nellie’s language.’ So Ran went in to Nellie and said: ‘Look Nellie, keep your language down a bit because of Ella.’

“And Nellie said: ‘Oh shit! Who does Lady Muck think she bloody is?’

“Now Ella had this big American theatrical trunk that she traveled. The next night we go to the theatre and there’s a knock on our dressing room door and Nellie came in and she said: ‘Ran, is the boy there?’ He said I was and she said: ‘Terry, I want you a minute. Get this bloody trunk out of the dressing room. We can’t move in here. This dressing room’s too small for the two of us and this bloody trunk.’ So I pushed the trunk outside into the hallway outside the dressing room and left it, and about ten minutes later there’s this knock on the door and it’s Ella and she says: ‘Terry, could you come and help me? I don’t know who’s done it, but someone’s pushed my trunk out into the hall, and I must have it in the dressing room.’ So out I go and I pushed the trunk back into the dressing room and that was that.

“Then the next night there’s another knock on the dressing room door and it’s Ella. I said: ‘What do you want, love?’ and she said: ‘I can’t find my reading glasses anywhere. I’m sure they were in my handbag but I’ve got an idea that Nellie picked them up and put them in hers. Now I know you are a friend of Nellie’s – would you come in and have a look?’ So I did and, sure enough, there were Ella’s glasses in Nellie’s bag. Just the one pair. Now ten minutes later there’s another knock on the door and it’s Nellie: ‘Is the boy there? I want you a minute.’ So I go into her dressing room and she said: ‘That woman! She’s got my reading glasses! I can’t find them anywhere.’ I said: ‘Are you sure?’ She said: ‘Yes – they were on the make-up tray and they’re not there now. Look in her handbag.’

“I said: ‘You look.’

“She said: ‘No, you look in her handbag.’ So I looked in Ella’s bag and there were Nellie’s glasses as well as her own. And that’s how the week went on – not exactly squabbling with each other but certainly not getting on together. Then on the Thursday Nellie was off with a cold and she was staying at the Queen’s Hotel in Leeds and on the Friday we went to see her and we’re sitting talking to her in the hotel bedroom and she says: ‘You know what, Ran and Terry? I’ve come to the conclusion that there’s only one person in this show that understands me and that’s Ella.’ We just had a quiet laugh.”

Here’s a clip of Nellie Wallace ‘at home’ rather unconvincingly doing some housework and gardening and trying to feed an apple to a dog. The original footage is silent, and is here accompanied by her singing Under the Bed. About two-thirds of the way through another woman joins her – there is a strong facial resemblance, so it could be either a sister or perhaps her daughter.

In Edinburgh: Nellie Wallace, Gertie Gitana, June Franey (Mrs G.H. Elliott), Don Ross, G.H. Elliott and Ella Shields.

WHEN Thanks reached Edinburgh the cast were astonished to find the city council had provided an open landau carriage, complete with horses and liveried coachman, waiting outside the hotel to take them on a tour. As the carriage door was opened for her, Ella said: “I’m all for showmanship, but isn’t this more like a circus?” Nellie slapped her on the bottom and said: “Get in the bloody thing.”

As part of the tour they visited a trade exhibition, where a salesman of patent remedies tried to interest Nellie in a glass of health salts, exhorting: “C’mon, gel, have a go. It’s great for your bowels.”

Nellie turned to Don Ross and said haughtily: “Mr Ross, will you kindly inform that gentleman that Miss Wallace’s bowels are in excellent working order.” Still fuming, she added: “I don’t know what the country’s coming to. Here we are at this lovely exhibition, being treated like ladies and gentlemen, and some upstart interrogates one about the state of one’s bowels. Presumption, my dear. They would never have asked Vesta Tilley about her bowels. But, then, perhaps the poor bitch never had any.” (1)

Ella Shields was just as eccentric in her own quiet way. Ross: “In the contracts it was stipulated that the artists were not to make curtain speeches because they held the production up and, anyway, all the audiences wanted to do was sing along to the old songs. But one night Ella decided to make a curtain speech. Afterwards I said to the stage manager: ‘Could you ask Miss Shields to come and see me please?’ When she arrived I said: ‘Look, Ella, for a start I don’t think you knew what you were saying. Do you realise you wished the audience Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year – and its only September the 26th? And that you said . . .’ And I couldn’t go on because I saw her lower lip begin to tremble and she put a hand up to her mouth. So I said: ‘Look, darling, we’ll have a bottle of champagne together in a little while and forget all about it.’ So it passed off – but she didn’t make any more curtain speeches. Not until the very last night of Thanks, anyway, when all the artists did.

“Another time she claimed that the cats’ eyes running down the middle of main roads worked by electricity, and nothing we could say to her would shake this conviction. She said: ‘I know the man who invented them. He’s a very dear friend.’ So one day I stopped the car and said: ‘Look here, Ella. You can see that they’re just reflections – bits of glass.’ And she said: ‘You can’t fool me. They wouldn’t switch them on during the day’.”

She may have been whimsical and scatterbrained in private, but onstage Shields was totally magical. Ross: “I was taking Harry Lauder and his niece Greta through the pass door after our opening performance at the Glasgow Empire and he stopped in the passage and held the lapels of my jacket. ‘I’ll tell you something,’ he said, ‘and I’m a Scotsman, if you know what I mean. I’d pay my admission money just to watch Ella Shields walk onto a stage and take her calls and walk off again. She’s so perfect. Man, she’s exquisite’.”

Late in 1948 Nellie’s daughter was moved into a hospice. She died on a Thursday, was cremated on Saturday, and Nellie was back with the show the next day. The company tried to rally round to comfort their old pal in her grief, but she rebuffed all approaches, refusing to eat and spending long periods alone in her dressing room, weeping. Ross managed to persuade her to see a theatre doctor, who told him Nellie was desperately ill. She pleaded with him to let her work on, and he agreed on condition that she rested all day and had constant medical supervision. Thanks for the Memory at the The Royal Variety performance was Nellie Wallace’s last appearance on any stage. Three weeks later she died in a nursing home, aged 78, when a valve in her heart burst.

HER replacement, in January, 1949, was her old rival Lily Morris, tempted out of retirement because of the outstanding success of Thanks. Morris, born in London in 1884, made her first stage appearance when she was ten. The possessor of a fine contralto, she went on to become a chorus singer with many hits: Don’t Have Any More Missus Moore, Only a Working Man, In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree and her best, Why Am I Always the Bridesmaid?

Why am I always the bridesmaid – never the blushing bride?

Ding-dong, wedding bells

Only ring for other gels.

But one fine day – oh, let it be soon –

I shall wake up in the morning on my own honeymoon.

Although this is essentially a song of loneliness and despair, about a portly, middle-aged woman seeking a husband but continually being passed over, Morris made it irresistibly funny, even when recounting how her own mother seduced and then married one of her suitors (“being a widow,” explained Morris, “she knew what to do”). All through the song she put in hilarious little bits of business: casting herself to the ground in supplication, peeping coyly from behind the wilting bunch of flowers she carried. The side-splittingly funny bit came at the end, when the tempo increased and Morris lifted her skirts to expose chubby, bloomer-clad legs and hob-nailed boots and then rushed around the stage in the most wonderfully-mad dance, somehow seeming to defy the laws of anatomy as she rotated her legs at the knee, tap-dancing, prancing and curtseying with tremendous vigour while every few seconds the lower part of each leg went round in a circle.

It looked physically impossible, and in a lifetime of watching great eccentric dancing I have never come across anything else quite like it. You don’t need to take my word for it; thankfully, film of her singing Bridesmaid and demonstrating this quite astounding legmania survives in the early British musical Elstree Calling (1930), part-directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

And here it is . . .

Because she had been retired for so long, on her first night with Thanks this great trouper was as nervous as Ran Sutton, grabbing Don Ross and insisting he accompany her to the wings. “Come with me, Billy-boy,” she said. “Don’t leave an old girl in the lurch.”

THE final curtain of the first Thanks for the Memory fell at the Brixton Empress, where it had started two years before, on December 2nd, 1950. There would be further versions, with new/old names coming in – Sandy Powell, Albert Whelan, Billy Russell, Marie Lloyd Jr., Cavan O’Connor and a chastened Hetty King – and Sutton, Doogan and Danvers continued touring with the show right through the 1950s and into the 1960s. Thanks for the Memory meant many things to him, Don Ross told me. It was the professional highlight of his career, it brought him into direct contact with stars he had admired since boyhood, it acquainted a new generation with the fabulous entertainment of the past, and, most of all, it represented a last showcase for his adored Gertie.

And so we say farewell to Thanks for the Memory with a little poem Nellie Wallace often recited to close her act at London’s bawdier halls:

“The morning sun can kiss the sky. The flower can kiss the butterfly. The morning dew can kiss the grass. And you, my friends, can . . . goodnight!”

Thanks for sharing the memories, Don

AFTER the final performance of the first Thanks for the Memory tour in 1950 Gertie Gitana lived in blissful retirement with her beloved ‘Bill’ at their home in Hampstead, which they called Neldean. Her reputation as one of the brightest of all music hall stars was secure, Nellie Dean was still sung in pubs all over Britain at closing-time, and a street near her birthplace had been named after her. She resisted all suggestions of another comeback and developed a passionate interest in the Stock Market. In 1957 she died of cancer, aged 70. On her last morning her husband was sitting at her bedside when she suddenly woke and said: “Fancy them naming that street in Hanley after me.” According to Gitana’s biographer, Ann Oughton, Don placed his head on her pillow, his face close to hers. “Somehow she managed to find the strength to put her hand at the back of my neck and press my face closer to hers. She held it there for a time and whispered: ‘Thank you, Bill, for all your kindness, all your goodness to me, dear, and for all your love. Don’t try to live with me when I am gone. Nobody should ever live with the dead. Be happy, darling’.” (2)

ELLA Shields continued to take Burlington Bertie around the variety circuit after Thanks for the Memory. In August 1952 she was engaged as guest artist at Middleton Towers holiday camp. At the band call the 74-year-old star complained of feeling tired but refused a chair and did the rehearsal standing. During the show that night her physical condition deteriorated and, for the first time in 40 years, she changed the intro to her famous song. Normally, the band would vamp indeterminately while she prowled the stage doing bits of comical business with her cane, cuffs and topper and then she would go to the microphone and croon “I’m Bert” – the first line and the signal for the band to go in to the accompaniment proper. But that night, instead, she said in a musing and sad way: “Yes . . . I was Burlington Bertie,” finished the song, walked into the wings and collapsed from a cerebral haemorrhage. She died in hospital three days later without regaining consciousness. At her funeral the floral tributes were dominated by a gigantic wreath with just a name scrawled on the card: Buck.

RANDOLPH Sutton performed with tremendous verve in music hall revival shows until his death at the age of 80 in 1969. He made several television appearances and even featured as a pub singer on Coronation Street. Ran topped the bill at the City Hall Theatre, St Albans, just a week before he died and on the day of his funeral he had been due to go into the studios to re-record some of his old hits. He left most of his estate of £26,760, plus his stage poodle, Pierre – who had delighted audiences by running onstage at the end of the song Your Dog’s Come Home Again – to Ernest ‘Terry’ Doogan, his companion of 33 years, and an annuity of £312 to his wife Nellie, from whom he had been separated for more than half a century. For many years an In Memoriam notice appeared in the pros’ newspaper, The Stage, on each anniversary of his death. It read: ‘Sleep tight, Ran. No more nerves. From Terry (The Boy).’ Terry died in 2005, aged 83.

G.H. Elliott died at his home in Brighton in 1962, aged 78. In a piece in The Guardian in 1971, Keith Dewhurst recalled meeting The Chocolate Coloured Coon ten years previously, when he was appearing for a week in Wigan: He was lean and dry and twinkly, and his voice had a fascinating hoarseness. He had dark eyes that looked straight at you and made you feel very special, and his suit was very dapper in an Edwardian style that hid the wearer’s social origins behind a sort of gentlemanly rakishness . . . And I can remember that just as my first shock had been to see Elliott so spry and eager, so my second was to realise that he was, in fact, old and tired. His hair, I imagine, was a little dyed and the sheer effort of being so welcoming and amusing exhausted him. At pauses in the conversation he grinned but had nothing to say. Finally, his wife said: ‘It’s time for Mr Elliott’s rest.’

When he laughed at this he seemed young again, and when he shook my hand with his own that had many times shaken the hand of Marie Lloyd, his grasp was firm again and he did a little shuffle so that I looked down at his feet and saw how neat they were and how his shoes twinkled with polish. Whatever he thought about me or his predicament, whatever vanities or humiliations were troubling him, his courtesy was immaculate. He was perhaps a shade too keen to welcome me and a shade too obviously glad to leave me, and yet when he said he must be rested for his performance he implied not his own failing powers but an ideal of professionalism. (3)

TALBOT O’Farrell, aka Jock McIver, aka William Parrot, was already quite ill during the last few months of the first Thanks for the Memory, and he died aged 74 in1952, as did the great Lily Morris. Billy Danvers continued to be Always Merry and Bright for many years and was working full-time until just two weeks before his death aged 80 in 1964.

AFTER Gertie died Don Ross became reclusive for a while then shook himself out of his depression and picked up his career as a producer and agent. With Ray Mackender and Gerry Glover, he founded the British Music Hall Society – still going strong – in 1963 and was its first chairman. As Britain’s leading authority on the subject, he was often called upon by the BBC to contribute to radio or television programmes about the halls and the stars who populated them. He tried to retire in 1966, moving to Somerset, where he happily tended his kitchen garden and fruit trees. But it was hard to avoid the lure of the entertainment world, and two years later he accepted an offer from impresario Billy Marsh of Bernard Delfont Management to take charge of a show at Great Yarmouth and he remained in the business for the rest of his life. He died aged 78 in 1980 after a stroke, and was laid to rest beside Gertie at Wigston Cemetery after a service at St Paul’s, the actors’ church in Covent Garden, at which John Betjeman read the lesson.

All text Copyright Stephen Dixon 2013. A shorter version of this story appeared in The Guardian newspaper in the 1970s. All illustrations, except where specified, from Stephen Dixon Collection, acquired from various sources over a 40-year period and in many cases provided by the artists themselves in the 1970s. If anyone has copyright or permission issues, please contact me.

Other sources:

(1) and (2) Thanks for the Memory: A Biography of Gertie Gitana, self-published by Ann Oughton (Pentland Press, 1995).

(3) The Guardian, June 30, 1971.

stephendee

| #

Doesn’t ring a bell with me, Stefan, tho it’s a very typical Sarony line. Anyone? Stephen

stefan Beard

| #

Just been reading the Leslie Sarony piece. Absolutely fantastic. Well done. A question if you don’t mind. Does anyone know the the title of the Leslie Sarony song that has the line “Oi ! how you gettin’ on? ” in it ?

ruskimic

| #

I do hope you can help me. I have been searching for many years for my Great Uncle Mr Albert Edward Rayner who went under the name of Dan Rayner. I believe he worked the Music Halls but I do know for sure he worked with Fred Karno. When Charlie Chaplin left Fred in America over a Pay dispute the American backers of the tour insisted that my Great Uncle Dan Rayner be called over from England to take Charlie Chaplin’s Place. It appears Dan was liked more at that time in America than Charlie was. Another man in the troupe at that time was Stan Laurel. When the show folded Dan was asked along with Stan to stay in America. As we know Stan stayed and found he fame and fortune. Dan however chose to return to England. He was last that I can find in a play Dick Wittington at the Empire Theatre advertised in the a local paper in Durham in 1948. Unfortunately I have not been able to find when or where he died. I am hoping that maybe on your search you came across some info on Dan Rayner. I live in Australia so am unable to search all the death records for England with out it costing me a fortune. So any help you maybe able to give me would be really appreciated. I know he went to America twice and once to Australia and also once to South Africa. I do know he was married to a lady named Barbara Robinson and they had a son Conrad Paul Rayner but I have been unable to find any thing out about these two members of his family. I do know they separated before 1935 and he lived with another lady named Phyliss but as to her last name I have no idea. I have been searching for nearly 10 yrs now and I don’t think there is any thing left on the net that can help me. You it would appear maybe my last chance. I will keep my fingers crossed that you did come across some info on him or you know some one that maybe able to help. He went to America in 1913 on the Lusitania and it shows at this time he is married. He then returns to America in 1914 on the ship Adriatic. I do believe he also did a radio show after 1935 for quite some time but do not know the name of that show. I do hope you can help in my search for my Great Uncle.

I also might add my great grandfather was Edwin Richard Barwick. He was also a Music Hall performer and appeared in the first Royal Command Performance. If you get the picture and Index to that even you will see him standing next to Pavlova. I would love to hear any information you may have found out about him. I do believe he was one of the first members of the charity named water rats, I know star was spelt back wards to get the rats part. Edwin did a lot of work for this charity in his day. What I would love to know is if there is any recording of Edwin Performing and if so how I would go about getting a copy or seeing any recording. I do have a photo copy of an old theatre bill with my grandfathers name boldly written on it. Again any help would be appreciated.

All the best and I look forward to hearing back from you in the near future

Kim Rayner

my email address is ruskimic@yahoo.com.au