Sandy Powell

SANDY Powell’s best-remembered routine, buffed to a dazzling shine over half a lifetime, was still very funny in the 1970s even though the art it parodied had dwindled almost to a footnote in theatrical history.

“Ventriloquism! That is the thing of the day,” his asthmatic old soldier would wheeze confidently at the start, and during the inevitable series of disasters that followed – from a severe injury caused by the ceremonial sword hanging from his baggy scarlet guardsman’s uniform to the total disintegration of the malevolent and motheaten military dummy – the expression on those crumpled features gradually transformed from bland smugness to helpless, testy resignation as control of the act slipped from his grasp along with the doll.

The bedraggled false moustache that hid his lips fell off a number of times and had to be stuck back on. The dummy sang while Sandy ostentatiously drank a glass of water; the curtains behind him ‘accidentally’ parting to reveal it was his assistant providing the piercing falsetto. “Now they’ll all know ’ow it’s done,” Sandy grumbled wearily.

He stared balefully out at the audience. “Can you sing and drink a glass of water at the same time?” he demanded. “It’s impossible!”

Further signs that his initial confidence had been misplaced began to be evident as he introduced the dummy to his assistant.

Sandy: “Now tell the lady where you come from, my little man.”

(Dummy makes unintelligible spluttering and choking noises).

Assistant: “I beg your pardon?”

Dummy: (with great difficulty) “Nullgerangton.”

Assistant: “Where?”

Dummy: “Nullgerangton.”

Assistant: “Where?”

Sandy (shouting): “WOLVERHAMPTON!” (Muttering to himself): “I wish he’d said Leeds.”

Sandy became distracted and his hand stuck out of the dummy’s neck-hole, waving around the stick to which its head was attached. “Oh dear,” he sighed. “I seem to have given the game away again.”

THE act was a master humorist’s brilliant evocation of all that had been tired and third-rate in variety, hilarious and strangely poignant, each pause and inflection part of a masterclass in comic timing for those who cared to watch and learn. But there was nothing third-rate about Sandy Powell himself. He had been one of Britain’s wealthiest and most successful entertainers, star of a series of movies tailored to his particular talents in the 1930s and 1940s, and he had sold a staggering seven-and-a-half million gramophone records of comedy sketches and monologues. He created radio’s first real catchphrase: “Can you hear me, mother?”

For fifty years he was also a top pantomime performer, moving from Buttons to Dame as he aged, and at least one of his innovations still lives on: he is said to have been the originator of the routine based around the phrase: “Look out – he’s behind you!”

The shrewd Yorkshireman had been prescient, in the 1930s anticipating the kind of tie-ins and merchandising now considered obligatory in the selling of any performer. There was a 75,000-strong children’s club, the Sandy Powell Gang of Good-Deed Workers (Rule 6: Whenever you meet the Chief Gangster, that is myself, you are to fold your arms, walk straight up and say ‘Hello Sandy’), enamel lapel badges and ceramic mugs bearing his likeness.

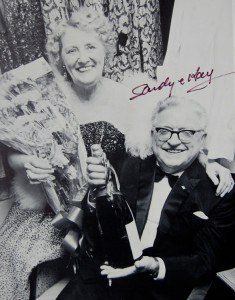

The dumpy, bespectacled little comedian was as old as the century and appearing in The Golden Years of Music Hall with Leslie Sarony, Bob and Alf Pearson and other survivors when I first met him in Manchester in 1971. In his dressing-room after the show he was the soul of affability as his wife Kay – it was she who had been discovered behind the curtain when the dummy sang – fussed around sorting out his props and making cups of tea. The shock of thick white hair had a ginger rinse through it to keep it still vaguely sandy-coloured, and dye now and then trickled down his forehead as we chatted, to be wiped away by Kay with an exasperated “tsk.” His nylon shirt had several burn holes on the front from the dropped cigarettes he used in another of his celebrated set-pieces, The Incompetent Magician.

I’d watched him doing it earlier. During the act, during which he never spoke a word, he dramatically covered his hand with a cloth and pulled it away with a flourish to reveal a bobbing white dove that he stroked as it perched on his fingers. After the applause died down Sandy wearily folded the dove in half and stuffed it into his pocket. He was not like Tommy Cooper, an inept magician who knew he was bad and laughed along with the audience. Sandy’s stance was ambiguous – it was never clear if he was a terrible magician who suffered from delusions of competence, or just an exhausted old trouper, nearly at the final curtain, past caring if the audience “know ’ow it’s done.”

Time for a clip of Sandy’s ventriloquism routine, from the 1980 Royal Variety Performance.

Whichever, Sandy was deconstructing the basic conventions of music hall in a way that had been unusual and rather daring for its time – having the bravery to go on stage and deliberately be rubbish and risk the audience not getting the joke. He liked to tell the story of overhearing two men on their way out of the theatre. “That magician in the first half was bloody awful,” said one. “I know,” said his friend. “But he wasn’t as bad as the ventriloquist in the second.”

But almost everybody did get it, of course, because he was Sandy Powell, Britain’s best-loved comedian. That gave him the confidence to go out on a limb. He didn’t need to; he could simply have pelted the audience with gags and suggested they go out and buy his records – typically, when he started recording he had set up a royalties deal that had helped make him a millionaire. But Sandy was intrigued by how far he could push comedy, where the safety nets were and whether or not they would catch him. And, unlike more recent boundary-stretchers, he managed to do it without ever being aggressive, sweary or blue.

And here’s the magician.

HIS mother Lily, who had been born in a Yorkshire workhouse, was a small-time turn who toured the smaller halls in the North of England in the 1890s with a puppet act, Lillette’s Living Marionettes. In 1899, when she was eighteen, she married a stagehand and the couple set up home in a tiny terraced house in Rotherham, where Albert Arthur Powell was born in January 1900. Powell Snr, who called the baby Sandy because of his bright red hair, was a drunk and a womaniser who disappeared four years later.

Penniless, Lily had to go back on the road to support her child, getting stage jobs whenever she could but mostly working as a singing waiter in pubs, Sandy hiding behind the piano in the bar. The boy had virtually no education, even though the law required him to attend school at each town where Lily was working. Sandy reckoned his whole schooling amounted to less than six months. Lily taught him to read and write. She also groomed him in stagecraft, and he first appeared before the public as a boy soprano planted in the audience and invited to stand up and sing by Lily. When he was nine Sandy went on stage alone (with a fake birth certificate to hand; children were not allowed to appear alone under the age of eleven) as a singer, and he also helped Lily in the marionette routine. Offstage, he was developing an act tap-dancing and mimicking stars of the day.

“My voice broke in 1912 and that’s when I first started to do comedy. I started at the old Empire Theatre in Easingdon Colliery, County Durham. My great favourite then – my idol – was Harry Weldon, and I based my style on his. And pinched his gags! He was doing Stiffy the Goalkeeper and he was absolutely my idol. Then I saw him at the Palace, Manchester, playing Buttons in Cinderella. And I used to go into every show while my mother was working the pubs around Manchester. I used to go in the gallery – twopence-ha’penny I think it was – every performance to see Harry Weldon.”

Weldon had a curiously sibilant delivery, whistling on every ‘s’ in his patter, and his Stiffy the Goalkeeper characterisation – an idle but loquacious player doing everything in his power to avoid the ball coming near him – had long been a favourite with provincial audiences. He had another act, The White Hope, in which he introduced a popular catchphrase: “Tell them what I did to Colin Bell” (Bell was a famous heavyweight boxer), adding more quietly, “but don’t tell them what he did to me.”

As mother and son trundled around the tattier music halls and dismal theatrical lodgings, often reliant upon public soup kitchens or the kindness of strangers, Sandy learned other lessons, too, about self-sufficiency and the value of money, about how a good deed would always be rewarded somewhere down the line. Financially astute as he became, Sandy was never less than open-handed and generous – when he was a top-earner he would be the first to discreetly slip a few quid into a struggling old pro’s pocket, or give a leg-up to a talented youngster, or volunteer to take a pay cut if a show wasn’t doing too well. And his innate decency did find its reward towards the end of his career, when the world of British show business rallied round to support him when he suffered a devastating professional blow.

He and Lily were working a double-act when the First World War broke out and they continued to tour on the halls and in cine-variety. On one bill the only other act was a young girl named Grace Stansfield, later to become better known as Gracie Fields. “We used to go round the ‘smalls’ and the cinemas, where they used to have two turns while the projectors cooled down. Then we got on to the cheaper music halls, like the City Varieties in Leeds.”

When times were particularly tough Lily went back to the pubs and Sandy got casual jobs labouring in factories, and he also had brief stints looking after the donkeys on Blackpool beach. He was fifteen years old, still basing his act around Harry Weldon, struggling to find his own comic identity, when the big break came.

In the 1930s.

“Mother and I were at the Empire Theatre, Dewsbury, and there happened to be a London agent in the theatre, a young man named Bertram Montague, and he sent a note round asking if we would meet him in Leeds the following morning, and he told us that he was going to try to get us a trial with the Stoll tour. Now if you got a Stoll tour in those days then that was the hallmark of success. He got me a two-week trial at two shillings and sixpence a week at the Shepherd’s Bush Empire in London, which is now the BBC television theatre, and the Ardwick Green Empire – I’m afraid there’s just a blank space where that lovely theatre used to be – and I did all right, thank goodness, and I got more Stoll dates. Then we worked for Moss Empires and that started me being successful.”

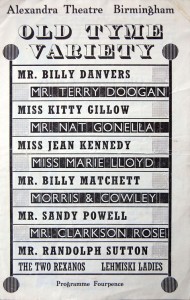

Sandy was now appearing on bills with top names such as George Formby Snr, Little Tich, Marie Lloyd, Chirgwin the White-Eyed Kaffir, Nellie Wallace, Tom Costello, George Mozart, Vesta Tilley and Hetty King. When it became obvious that her son worked far better on his own, Lily retired.

“The first time I topped a bill at a good theatre was at the Palace, Blackpool, in 1918, and that was the first time I could call myself a star. Then I did a pantomime, Handy Andy, at the Princess Theatre, Glasgow, which ran for 18 weeks. Well, time went on, and I went around the smalls, with occasionally a good theatre, and then in 1928 I did a summer show at the Winter Gardens in Blackpool and I also made my first radio broadcast. It was from a little room at the Tower.”

THE next year came the record that changed his life. “They asked me to make a record and I asked them what they wanted me to do, because I can’t sing. They asked me what I was doing on stage that week – I was at the Palladium – and I said it was a sketch called The Lost Policeman. I did a test record of it, and I was booked to go to South Africa just afterwards. The recording company said: ‘We think that’s all right and we’re going to put it on the market.’ Well, I was in South Africa for three months and when I came back, to my great surprise, the recording manager came round and he said ‘I’ve got good news for you, Sandy. The Lost Policeman is a great success.’ And he handed me a royalty cheque for £175, which in those days was a hell of a lot of money. The record sold half a million, and I earned a ha’penny a record.”

Vocalion had offered Sandy a lump sum of £60 for the recording, with all rights retained by the company, or £30 as a recording fee and a royalty of a farthing a side. His instinctive decision to go for the royalties earned him a vast amount of money. Over the years he made nearly 100 records – “we churned them out like sausages” – for a variety of labels, and his income from royalties alone peaked at £12,000 a year, huge money in the 1930s.

The Lost Policeman opens with Sandy on his beat, ruminating to himself in his trademark slow, grumbling whine: “Oh what a life, what a life to be a policeman. You know, I’ve been on my beat all day and I haven’t had one case yet, not one case. Hullo – here’s a little boy coming along. I wonder what he wants. Hello, son. What’s the matter?”

Percy: “Can you tell me where I can find a policeman, please?”

Sandy: “I beg your pardon?”

Percy: “Can you tell me where I can find a policeman, please?”

Sandy: “What do you think I am, a sea-lion or something? Why? What do you want a policeman for?”

Percy: “Our ’Erbert’s fell in the river.”

Sandy: “Your ’Erbert’s fell in the river? Oh I am sorry, I really am. Your ’Erbert’s fell in the river, eh? Oh it is a shame. Has he – er – has he been in the river very long?”

Percy: “Oh no, just now.”

Sandy: “Just now? Well, that isn’t so bad then. He’ll get used to it when he’s been in a bit, you know. Has he ever been in a river before?”

Percy: “No.”

Sandy: “Oh well, it’ll be a change for him, then. Can your ’Erbert swim?”

Percy: “No.”

Sandy: “Oh well, now’s his chance to learn, then. Well, I’ll take a few particulars down if you don’t mind . . .”

And so The Lost Policeman rambles on, with Sandy continuing to take measured and irrelevant notes while Our ’Erbert presumably threshes about in the river, drowning. This type of comedic stance – trivialising mounting disaster and treating it as a distraction or nuisance – was used by other comedians besides Powell. Perhaps the most famous example is Robb Wilton’s Fireman Sketch where, as a harrassed station officer, the comedian reminisces amiably and chats inconsequentially – “What’s the address? Grimshaw Street – Grimshaw Street . . . now wait a minute, I know it as well as can be, but I just can’t place it. No, no, no . . . don’t tell me, let me try and think of it for myself. Grimshaw Street – oh, isn’t that annoying” – while a woman’s house is burning down.

Here’s a sketch that runs along similar lines, from 1930, as Sandy blandly welcomes home a neighbour on whose home he has been keeping an eye. Click here

Over the next ten years Sandy performed many other gramophone occupations equally unsatisfactorily in sketches mostly written by himself, including mountaineer, dirt-track rider, jockey, fireman, tram-driver, solicitor, plumber’s mate, zoo-keeper, MP, doctor, taxi-driver, barber, grocer, boxer, burglar, farmer and window-cleaner. He found himself ‘amongst the loonies,’ swimming the Channel, on a South Sea Isle, joining the nudists and, in Sandy Joins the Short-Shirts, flirting with fascism.

‘THEN I started putting on my own shows – road shows – in 1930, just as the talkies were coming in. The talkies murdered variety and the theatres but, through The Lost Policeman and my other records, I happened to stay successful. It was a cheap show I put on, but it continued until the war started. By this stage my record sales were averaging a million a year. That may not be many these days, but it was a hell of a lot then. And my little road show was doing very, very well.

“Now, about my catchphrase, ‘Can you hear me, mother?’ It was about 1931 and I was doing a record called Sandy at the North Pole, and it was being broadcast live at the same time. I was doing this sketch and I had to say: ‘Try and get my mother. I want to talk to her. She’ll be in the saloon bar of the Pig and Whistle.’ Anyway, I said: ‘Are you there, mother? Can you hear me, mother?’ This was just an ordinary line in the sketch that was repeated at intervals. I had a bit of patter and then: ‘Can you hear me, mother?’ and so on. This went on, and then I dropped my script on the floor and all the pages got mixed up. I was filling in and ad libbing and I said: ‘Can you hear me, mother?’ a few more times.”

It was only when people shouted the phrase after him in the street the day after the broadcast that he realised it had become identified with his name. “I didn’t intend it to be a catchphrase. It sort of caught on, and it’s never really been forgotten. Nearly all the famous catchphrases have been like that. Arthur Askey and ‘I-thang-yow.’ He just said that one day and it caught on. Robb Wilton with his famous ‘The day war broke out . . .’ I happen to know that he never meant it to be a catchphrase. It just goes to show that you can’t kid the people. They pick what they fancy, no matter how you try to push them.”

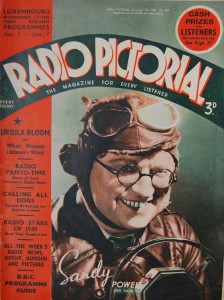

His first Royal Variety Performance, at the London Palladium in 1935, led to West End audiences becoming more receptive to his simple Yorkshire warmth, and Sandy’s radio shows in the 1930s, for the BBC or commercial stations – Radio Luxembourg’s series Around the World With Sandy Powell in 1938 was sponsored by Atora Shredded Beef Suet – were vastly popular. The BBC dropped him only once, on December 11th, 1936, when Edward’s abdication speech was deemed even more important than Sandy Powell.

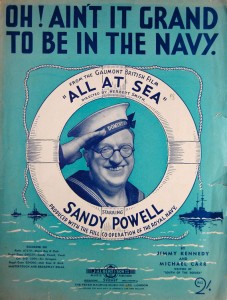

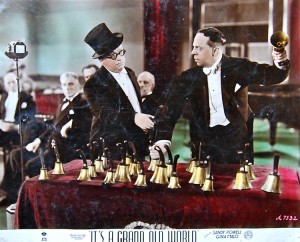

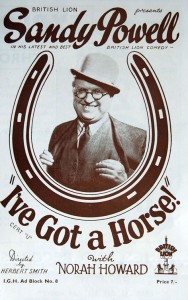

It was inevitable that he would go into films, and he starred in eight between 1932 to 1948: The Third String, Can You Hear Me Mother? Leave It to Me, It’s a Grand Old World, I’ve Got A Horse, All at Sea, Home From Home and Cup-Tie Honeymoon. The films were unpretentious, homely fare, far more popular in Lancashire and Yorkshire than in the snooty South, and those I’ve seen seem laboured and unfunny now.

“When war broke out I was too old to join up, so I was one of the first to volunteer to go abroad and entertain the troops. I went to Italy, Morocco, Algeria and all the North African coast. I came back in 1944. Now in those days I lived in Russell Square, right in the heart of London. I came back when they told me something that surprised me. They said there were aeroplanes which came over and dropped bombs but which had no pilot. This was the doodle-bugs. Anyway, the first night home in England one of these things came down right in the middle of Russell Square, so the following morning I went straight to Drury Lane, which was the headquarters of ENSA, and I volunteered to go abroad again. So off I went to France with Florence Desmond and Flanagan and Allen.”

Sandy sings the title song from It’s A Grand Old World (1943), directed by Herbert Smith.

AFTER the war Sandy, like many another old variety pro, found himself less in demand as the theatres closed down and jazz, swing and crooners became the vogue. With the foresight he showed throughout his career, he saw that he and Kay, who was his third wife (his first marriage ended in divorce and his second wife died), could find a cosy and lucrative niche for themselves in summer shows if he operated as producer as well as star. “I used to do a summer season at the Pier Theatre, Eastbourne. When I saw the red light going up for variety, I thought ‘I must get into this summer season business’ in 1950, and I stayed there for twenty years. We produced and put on the show at the pier there every year and then, in 1970, we had a disastrous fire and the theatre burned down.”

The Powells lived nearby and watched helplessly as fire crews unsuccessfully battled to save the theatre. The old comedian’s investment in scenery, props – everything – went up in flames. Heartbroken, he turned to Kay: “I said to my wife: ‘Well, this is it. It’s the beginning of the year and we’ve lost our theatre for the summer. What on earth are we going to do? I’m seventy years old. This is the end.’

“And then things seemed to go the other way. The management of the Eastbourne Hippodrome, our opposition, who were presenting The Golden Years of Music Hall, said: ‘Sandy, make it twenty-one years in Eastbourne. Come and be in our show at the Hippodrome.’ Now I’d already managed to book something for the summer with Bunny Baron, who did a lot of summer shows, and Bunny rang me up and said ‘Sandy, make it twenty-one years. Go to the Hippodrome. I’ll release you from your contract.’ I thought that was a grand thing to do. It was a lovely gesture.

“So we went to the Hippodrome. It was a marvelous show. We had Elsie and Doris Waters, Leslie Sarony and Bob and Alf Pearson. During that year I also did quite a lot of broadcasting and television. I did my own half-hour show, Suddenly It’s Sandy Powell, I did a play, and then, to crown everything, I was chosen to appear again in the Royal Variety Show at the Palladium, thirty-five years after my first one. It was a great thrill.

“Then I was engaged to go to South Africa again, and a week before we were to sail, the management there contacted me and said: ‘Will you do a short film, a sort of trailer? We want to use it to advertise the show before you open.’ I said I would do it with pleasure, so we went along to the studio and I was doing my little burlesque ventriloquist act, and then I got the surprise of my life. In the middle of all this Eamonn Andrews came on and said: ‘Sandy Powell, This Is Your Life.’ That was the biggest shock I ever received.”

Another honour that came his way was when Bass Charrington wanted to open a pub in Rotherham named after him. Powell modestly vetoed the suggestion that it be called The Sandy Powell, and suggested The Comedian, with a Sandy Powell Lounge. “I opened the pub. I had to pull the first pint, so I was practicing with a friend of mine, who had a pub. I wanted to show them I could pull a pint. At the opening I said ‘Where are the pumps?’ and there were no pumps. Just a button to press.”

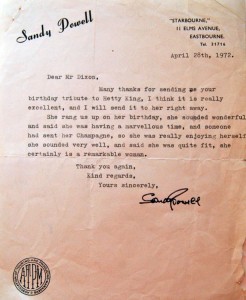

THROUGH the 1970s Sandy gently meandered around Britain with Kay in old-time music hall shows, almost always attracting good audiences except on the few occasions he tried the clubs and, like Wall and Jackley, found that the hard-drinking audiences were not patient enough for slow, old-style humour. He had always looked after his mother Lily, keeping her in luxury until she died, and he was a caring friend, too, particularly to the formidable Hetty King – whom he described as the finest artist he ever worked with – in her cantankerous old age. Part of a letter to me dated February 16th 1972 runs: ‘Hetty was taken ill the last week in Swindon and we had to leave her there in the hospital. She was very ill with bronchitis. However, I have phoned her tonight and she came home a week ago. Says she doesn’t feel quite herself yet, but listening to her on the phone her voice sounded wonderfully clear. I told her not to go out while it was so cold.’

Guardian photographer Don McPhee and I enjoyed Sandy and Kay’s hospitality at their home, ‘Starbourne,’ in Eastbourne, a couple of times, and it was in their living-room that he dug out his dummy and climbed into his old ventriloquist costume to be photographed. He was so kind and funny offstage, telling stories of long-ago, impersonating stars he’d appeared with sixty years before; a living link with Marie Lloyd, George Robey and Vesta Tilley. He had the charming gift, possessed by few, of radiating an instant friendship that seemed totally sincere, of making you feel that he had taken a great shine to you, that there was something about you that he really liked. You left his company glowing. He was such a very nice old man.

Unlike some of our veterans, he did not resent the stars of the 1970s who had supplanted him and his ilk. “You know, people say: ‘Ah, the good old days. The stars are not what they used to be.’ Well, I don’t agree with that. We have very, very wonderful stars today. You look at Max Bygraves, Morecambe and Wise, Frankie Howerd, Roy Castle, Ken Dodd. We have great talent nowadays. I’m sure that if they had been working during the great days of the music halls they would have been just as successful.

“I’ve been very, very lucky really,” he mused. “When the music halls started closing down I was able to adapt myself. And even now, thank goodness, I’m made welcome wherever I go. Perhaps one reason is that I’ve never used any blue material. I’ve never relied on blue material or sexy gags. I’ve always kept my act clean, and maybe that’s one of the reasons I’ve been able to carry on for so long.”

Can you hear us, Sandy?

SANDY Powell was awarded the MBE in 1975 and continued to work hard through the 1970s – sometimes three shows a day if there was a matinee. In the early summer of 1982 he and Kay were traveling by train to Coventry and Sandy, who been feeling a bit poorly for a couple of days, suggested they have a little drink. As Kay fussed around getting out the glasses and bottle of whisky, he said: “I think I’ll pack it in. Do you know what I think we’ll do? We’ll go on a cruise around the world.” His wife told him: “I’ve wanted to pack it in for a long time, too, but you were so happy working and you loved it so much that I never liked to say it.” At the end of his act that night he told the audience that it was at that very theatre, 50 years before, that he had first uttered the words “Can you hear me, mother?” on any stage. It was the last time, too; the following day the 82-year-old comedian collapsed and died from a heart attack.

Sandy bows out with a scene from Cup-Tie Honeymoon (1948), the first movie made by Mancunian Film Corporation at their studios in a converted church at Dickenson Road, Manchester.

All text Copyright Stephen Dixon 2013. A much shorter version of this story appeared in The Guardian newspaper in the 1970s. All illustrations, except where specified, from Stephen Dixon Collection, acquired from various sources over a 40-year period and in many cases provided by the artists themselves in the 1970s. If anyone has copyright or permission issues, please contact me.

stephendee

| #

Doesn’t ring a bell with me, Stefan, tho it’s a very typical Sarony line. Anyone? Stephen

stefan Beard

| #

Just been reading the Leslie Sarony piece. Absolutely fantastic. Well done. A question if you don’t mind. Does anyone know the the title of the Leslie Sarony song that has the line “Oi ! how you gettin’ on? ” in it ?

ruskimic

| #

I do hope you can help me. I have been searching for many years for my Great Uncle Mr Albert Edward Rayner who went under the name of Dan Rayner. I believe he worked the Music Halls but I do know for sure he worked with Fred Karno. When Charlie Chaplin left Fred in America over a Pay dispute the American backers of the tour insisted that my Great Uncle Dan Rayner be called over from England to take Charlie Chaplin’s Place. It appears Dan was liked more at that time in America than Charlie was. Another man in the troupe at that time was Stan Laurel. When the show folded Dan was asked along with Stan to stay in America. As we know Stan stayed and found he fame and fortune. Dan however chose to return to England. He was last that I can find in a play Dick Wittington at the Empire Theatre advertised in the a local paper in Durham in 1948. Unfortunately I have not been able to find when or where he died. I am hoping that maybe on your search you came across some info on Dan Rayner. I live in Australia so am unable to search all the death records for England with out it costing me a fortune. So any help you maybe able to give me would be really appreciated. I know he went to America twice and once to Australia and also once to South Africa. I do know he was married to a lady named Barbara Robinson and they had a son Conrad Paul Rayner but I have been unable to find any thing out about these two members of his family. I do know they separated before 1935 and he lived with another lady named Phyliss but as to her last name I have no idea. I have been searching for nearly 10 yrs now and I don’t think there is any thing left on the net that can help me. You it would appear maybe my last chance. I will keep my fingers crossed that you did come across some info on him or you know some one that maybe able to help. He went to America in 1913 on the Lusitania and it shows at this time he is married. He then returns to America in 1914 on the ship Adriatic. I do believe he also did a radio show after 1935 for quite some time but do not know the name of that show. I do hope you can help in my search for my Great Uncle.

I also might add my great grandfather was Edwin Richard Barwick. He was also a Music Hall performer and appeared in the first Royal Command Performance. If you get the picture and Index to that even you will see him standing next to Pavlova. I would love to hear any information you may have found out about him. I do believe he was one of the first members of the charity named water rats, I know star was spelt back wards to get the rats part. Edwin did a lot of work for this charity in his day. What I would love to know is if there is any recording of Edwin Performing and if so how I would go about getting a copy or seeing any recording. I do have a photo copy of an old theatre bill with my grandfathers name boldly written on it. Again any help would be appreciated.

All the best and I look forward to hearing back from you in the near future

Kim Rayner

my email address is ruskimic@yahoo.com.au