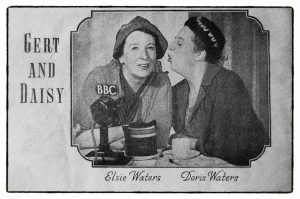

Elsie and Doris Waters

I STOOD in their hallway, hungover and travel-weary, smiling nervously as Elsie and Doris Waters inspected me. “I dunno, Doll,” said Elsie dubiously. “He looks a bit peaky to me. What we got in the fridge?”

“Nice bit of smoked haddock, Nan,” said Doris. She addressed me firmly as she ushered me into the drawing room. “We’re not going to talk to you until you’ve got some proper food down you, young man, and that’s that. Now you sit there and look at the paper while we make something to eat.”

I humbly did as I was told. As the sisters bustled around the kitchen next door, I could hear them talking about me over the clatter of pots and pans. “Do you think he’d want some carrots or mushrooms, Nan?”

“Dunno, Doll. Looks like he wants a stiff drink to me – ha-ha! Poke your head round the corner and see if he’s fallen asleep.”

The voices were older and posher, but the inflections and rhythms were exactly the same as their alter egos, heard in scores of music halls and a hundred radio shows: the voluble and indomitable Cockney pals, Gert and Daisy, whose funny and inspiring banter helped Britain win the Second World War, it was said. Their ability to rally the troops and sustain national morale certainly rattled the Nazis. “Germany calling, Germany calling,” intoned propagandist Lord Haw Haw in one of his broadcasts. “The people of Grimsby must not think that Gert and Daisy can save them from the might of the Luftwaffe.”

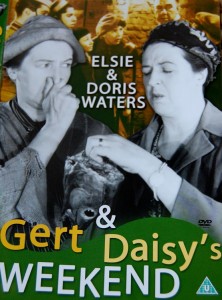

During WWll underground stations were used as bomb shelters. Here the girls bring a bit of that old party spirit to frightened and dispirited Londoners in a scene from their best movie, Gert and Daisy’s Weekend (1942).

When hostilities ended, Elsie and Doris Waters were awarded OBEs for their war work and were personally thanked by Winston Churchill. They were clearly women to be reckoned with, and I was a bit intimidated by them before we even met, to be honest. They were not keen on seeing me initially because they were fed up with being interviewed. ‘We find some of these people extremely casual,’ they wrote, ‘and they ask the most ridiculous questions, which we find very boring sometimes. Half of them don’t seem to know what they are doing, and we often wonder what our friends think when they read some of the rubbish written about us! You can have an interview if you like.’

And so began my friendship with two of the funniest, kindest and most delightful people you could ever hope to meet.

WHEN they came up with Gert and Daisy in 1930, Elsie and Doris Waters created a new style of comedy. Observational, chatty and relatively gag-free, with the humour based on the kind of witty comments and comebacks heard in real life, they were pioneers of a more naturalistic, confiding radio manner that Tony Hancock would later use to such good effect. There was strong audience identification with Gert and Daisy’s everyday gossip, delivered in a laconic, matter-of-fact East End drawl. Their subject matter is now dated, naturally, but their casual charm seems very modern.

In scripts mostly written by Elsie, they conjured up a whole cast to support them, whose doings and misadventures were witheringly discussed: Gert’s useless fiancé, Wally, and Daisy’s feckless husband, Bert. There was also the bane of their lives, malicious neighbour Old Mother Butler, and several more, all vividly real to listeners though they were merely referred to and not heard. It was rather like a humorous Coronation Street for radio, with just two characters evoking all the others.

Gert: “Daisy?”

Daisy: “Half a minute. Just putting Bert’s dinner in the oven.”

Gert: “Bert’s dinner?”

Daisy: “Yes.”

Gert: “What you got?”

Daisy: “Hash.”

Gert: “Hash?”

Daisy: “Hmm. Bert’s not fussy about his food, you know. Mind you, he’s a hearty eater, Gert. He’s not one of them sort of men, you know, if they made a pig of themselves it would be an improvement.”

Gert: “Ha ha. That’s good.”

Daisy: “I gave him a dish of macaroni one day, and he tried to put it on.”

Gert: “Oh no.”

Daisy: “Ha ha ha. He did a bit of cooking himself once. Made an omelette.”

Gert: “An omelette? I say.”

Daisy: “We haven’t seen the last of it yet. Bert used to clean his bicycle with it, but now we’re using it as a kettle holder.”

(Pause)

Daisy: “Been to the pictures this week?”

Gert: “No, not yet.”

Daisy: “Oh, I have. Twice. Oh, what a six penn’orth. Oh, I did cry. Used up both sleeves.”

(From the record London Pride Part 1, 1933)

The sisters quietly boasted that in their whole long broadcasting career – from the late 1920s to the early 1970s – they never once repeated the same sketch or song. They were even prouder that two elephants at London Zoo had been named Gert and Daisy in their honour. As recently as the late 1990s, Manchester United defenders Gary Pallister and Steve Bruce were nicknamed Gert and Daisy by fans, though only the older ones knew why.

Here’s a song that makes no sense unless you know that food rationing was in force in Britain during and for some years after WWll.

Recently, too, they have been embraced as feminist icons (though Elsie told me back in 1972 that “Women’s Lib would give Gert and Daisy the pip!”) and the subjects of university gender studies. “Elsie and Doris Waters are perhaps the most influential social satirists of the period,” claims Wheeler Winston Dixon, Professor of Film Studies, University of Nebraska.

A passage from an academic book written in 2003: ‘By forming their double-act around the ever-affianced Gert and the indissolubly married Daisy, they offered women an ontological choice: whether to find their meaning in themselves and with other women, or in the state of gender subalternity, through servitude to men and to patriarchy. By evoking laughter through song, music, patter, gossip, cross-talk, conversation, malapropisms, puns and jokes, through humour, wit, irony, burlesque, parody, satire, ridicule and a gynocentric misanthropy (counterbalancing misogyny), they also invoke a condition of delight, in which men and women might laugh at themselves, at their subject formations, their gender postures, their beings.’ (1)

The Ghost of Daisy: “Hark at him, Gert. Sounds like he’s swallowed a bloomin’ dictionary.”

The Ghost of Gert: “Oh, I say . . .”

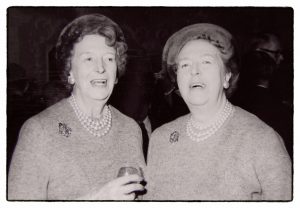

THE sisters lived together at Steyning, a village near Brighton, in a large bungalow with an immense picture window in the living room that looked out over the rolling Sussex countryside – “our Constable,” they called it. They referred to each other by childhood pet names, Nan and Doll, and there was an age difference they kept quiet about during their heyday. When I first met them, Elsie was in her late seventies and Doris ten years younger.

The age gap worked well for the sisters professionally: Elsie (Gert) was more of a creator of comedy and could be called the brains behind the act, while Doris was a more ebullient performer, and funnier, so big sister gave her most of the best lines. Although they were quite old ladies when we first met, I sensed there was something of the mother-and-daughter in their relationship. Sixty years earlier, Elsie would have been a sensible young woman when Doris was still a giddy child.

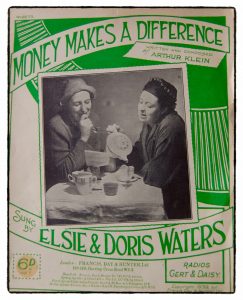

They began their career as singers and musicians, not comedians, and Gert and Daisy came about quite by chance. “We had been doing a bit of broadcasting,” said Elsie, “and we were heard by the Parlophone record company while we were broadcasting from Birmingham, and they thought our voices were suitable for recording. And so we made around six records of songs, which seemed to be all right. And then one Friday evening – we were doing Masonic work and concerts and things – we suddenly realised that we had to do another recording in the morning.

“We thought: what on earth can we do? Anyway, we decided to do a talking record for a change. Well, what shall we talk about? Well, we thought, people like wedding bells, so Doll sat down and she wrote a little tune and I put some words to it. We called it Wedding Bells and we did a little bit of chat, and that was the first of Gert and Daisy. After we had done it, we forgot all about it.”

Doris: “But you must remember, Nan, that we did wonder what we could call the characters, and I said: ‘I’ll call you Gert, because I like saying it,’ and you said: ‘I’ll call you Daisy, because there’s always a Daisy among us.’ Because, you see, we were born in the East End, and we knew how these women thought and talked.”

Elsie: “And in the end Gert and Daisy came to dominate the act. It was a case of the tail wagging the dog. After the success of Wedding Bells, we sat down and had a think about the situation and I realised that Doll was much better at telling stories than me. So she decided to tell funny stories and we wrote some humorous songs. And we’ve written songs ever since.”

They were born within the sound of Bow Bells to an intensely musical lower middle-class family. Their father, Edward William Waters, was an undertakers’ warehouseman, and when his children were old enough he formed the amateur Waters Bijou Orchestra. Elsie: “Our parents were very strict and we were taught that there was only right and wrong and nothing in the middle. There was no room for compromise. We were given training in every conceivable thing.”

Doris: “We had elocution lessons. We went to the Guildhall School of Music. Our eldest brother, Arthur, played the trumpet, cornet and post horn. Jack played viola. Bernard, another brother, played the second violin and another brother, Leslie, played percussion. Nan played second violin and I used to play the piano and, sometimes, tubular bells, heaven help us! We used to play temperance concerts, mothers’ meetings, church bazaars. As kids we didn’t fancy it much because all our friends were out playing and we had to stay in and practice. We had singing lessons – I was soprano and Nan was contralto.”

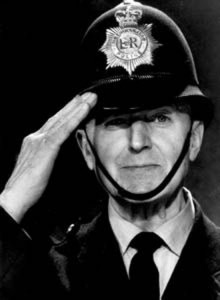

Brother Horace, who, as Jack Warner, became a film star and, on BBC television, the ‘ordinary copper’ Dixon of Dock Green.

(Incidentally, the Jack they referred to was Horace John Waters [1895-1981], who changed his name to Jack Warner and followed his sisters into showbusiness. After coming to prominence as a radio comedian in the 1940s, he went on to become a film star and, in the 1950s, even more famous as the eponymous London policeman Dixon of Dock Green in the long-running BBC television series.)

After the success of Wedding Bells, a big radio hit, Elsie wrote more sketches. Together they composed many songs, and Gert and Daisy became staples of pre-war entertainment, held in tremendous affection by the public. “The BBC used to ring us up and ask us to do a show and we went and did it and we never imagined that people liked it as much as they apparently did,” said Elsie.

Doris: “And it was very difficult to make a name on radio in those days, you know. There was the Midland Regional, the London Regional, the Northern Regional Service, and people would switch into any one of those. So if people decided they wanted to listen to you, they had to make a point of doing so.”

The sisters took Gert and Daisy around the music halls from 1935 onwards, but their debut was inauspicious. “The first time we played the London Alhambra they put us on as first turn,” said Elsie. “We thought this was terrible. We thought that if people wanted to see us, they wouldn’t have time to have their dinner. So I put an advert in the Sunday Referee, which was a paper they had in those days, which said ‘Elsie and Doris Waters. All last week first turn at the London Alhambra, three times daily, thus disproving the old saying that you can only die once.’ You know, people in the business still talk about that, and it was so many years ago now.”

They mapped out the lives of Gert and Daisy and their entourage with meticulous care and attention to detail. Everything had to have the ring of truth. “We never ask: what do we do now?” said Elsie. “We always ask: what would they do?”

Doris: “We wouldn’t say what they wouldn’t say. We know them too well, you see. Having been brought up in the East End of London, we know the way they think.”

Elsie: “I think we bring people into the picture. Everyone knows our type because our type is true. We are sincere about it. And another thing – although I don’t suppose people notice this – is that Gert and Daisy have never quarrelled. They have never been drunk. Bert was always fond of a drink, but not us. We’ve always been the homely types, which people enjoy. People can identify with us. The Manchester Evening News one time ran a competition, ‘What Do You Think Bert is Like?’ We had so many replies, and they were all different. They all thought Bert was their old man. All different kinds of women thought old Bert belonged to them. And all these characters were based on observation. We used to have a darling woman who used to come in and do the rough work, Mrs Mitchell, and she, I think, was the original of Daisy.”

Doris: “And so it goes on. I think it’s the fact that we talk about the same people all the time; otherwise, I don’t think Gert and Daisy would have lasted so long, because we get the come-back from Bert and Wally and all the other characters we have invented. You can’t run a thing on two people; otherwise, it’s just a series of gags, and that’s not what we do.”

THEY never married and always lived together. It was known that Doris had a great love affair just before the war, with an aristocratic member of the Diplomatic Corps, but wouldn’t go with him when he was posted to the United States because she felt it would harm her career and, besides, she and Elsie considered their place was in Britain as the political climate worsened. Elsie had a boyfriend, according to her niece, Pamela Lorraine, but decided not to get married.

There was a story going around in variety circles for years that at one point Elsie and Doris shared the same lover, someone high up in the BBC, but when I tentatively mentioned this to Ms Lorraine she dismissed it with an asperity that would have done credit to her aunts. ‘I have asked cousins if they know anything about lovers but nobody does,’ she emailed me in 2009, ‘and we feel it’s a shame to spread unsubstantiated gossip just because it sounds exotic!’ (2)

During the Second World War the sisters worked tirelessly. Doris: “We were put on the air for a fortnight after the 6 o’clock news. It was a terrible time. They had a terrific response to these broadcasts. The Ministry of Food gave us the subjects we were to put forward, like ‘Grow More Green Vegetables’ or ‘Eat More Oatmeal,’ and we thought: ‘Gawd, what’s funny about oatmeal?’ We used to give recipes. We lived on seven-and-sixpence a week before we did this Ministry of Food business. We thought that before we did it we’d better find out what it all cost. And, what’s more, we put on weight on seven-and-sixpence a week! That was in 1940. They had 60,000 letters at the Ministry of Food in a fortnight after our broadcasts and we thought that this was something so big that we had to do something about it.

“So we asked the Ministry if they would like us to go around and attend these meetings that were arranged through the gas companies and the electricity companies. The Ministry realised that women would want help with rationing, because they lived out of tins even in those days. And we said that wherever we were appearing, we would attend these cookery demonstrations. We used to do five a day sometimes, trying to get people to save food. Nobody paid us for this, of course. This is what we considered to be our war work. As a matter of fact, during the war we hardly made anything at all. And yet that’s the time when we were at the height of our fame . . . right at the top. But we felt we had to give it all up to do the war work. We felt we couldn’t do anything else.”

Elsie: “We went abroad to entertain the troops, and it was Gert and Daisy who took us there. What made us so proud is that the boys were so pleased to see us. They used to say ‘It’s not so far from home now you are here,’ and that meant more to us than anything we have done.”

IN the 1950s they went out to cheer up the troops again. Doris: “Just before Suez, we went out to the Middle East because they told us that the boys out there were having a rotten time. We were there for ten weeks and when we came back we had to do a radio broadcast. We took a taxi and the driver said: ‘I haven’t heard you on the wireless lately.’ We told him that we had been out to the Middle East, the Canal Zone. He said: ‘What’s it like out there?’ We said: ‘Jolly good, but it was a bit dodgy getting about sometimes’ and Nan said: ‘You know, we’ve only just got used to going about without an armed escort.’ He said: ‘Blimey, what have you got to protect?’ Isn’t it lovely? We just fell about on the pavement.”

Elsie: “But a remark like that can be tucked away and used, because all good comedy should have truth. Unless Gert and Daisy speak the truth, it’s no good.”

The sisters starred in a few films in the 1940s, of which the best is Gert and Daisy’s Weekend (1942), in which the girls escort a group of evacuee children from London to the comparative safety of the countryside. Early scenes showing Gert and Daisy entertaining Londoners sheltering in tube stations are wonderfully evocative of wartime life.

The first radio series built around the Cockney pair was Gert and Daisy’s Working Party in 1948, and a major variety series, Petticoat Lane, came the following year. Their greatest success was Floggit’s, which ran for two years from 1956, in which Gert and Daisy inherited a village general store and had to deal sternly with various characters played by Ronnie Barker, Joan Sims, Anthony Newley, Hugh Paddick, Ron Moody and Kenneth Connor.

“If the BBC had any sense, we could have been the original Coronation Street-type television show, because we talked about people,” snorted Doris. “We built up the characters of Bert and Wally, Old Mother Butler, Eadie and all the people round the corner and so on. We never said that it could have turned into a Coronation Street, but other people have said so.”

But the move to television, 1959’s Gert and Daisy, on ITV, was something of a disaster. Devised by Ted Willis, who created their brother Jack’s Dixon of Dock Green, the series had Gert and Daisy as landladies of a theatrical boarding house. The sisters were constricted by corny and unfunny set-ups, and the scripts were written by others. In the Daily Mail Peter Black wrote: ‘The dear old things did their best. The idea that any alteration of their technique could be necessary for television had not occurred to them, but as it had not occurred to anyone else one cannot reproach them too bitterly.’ (3)

The main problem was pinpointed by Doris to Philip Phillips in the Daily Herald: ‘Gert and Daisy – Elsie and Doris Waters – are angry. Their first-ever TV series has been given the thumbs down by the critics . . . Doris said: “We don’t think it’s too bad. A lot of viewers have said they like it. What do you think is wrong?” I replied: “It lacks the wit of your radio shows, and the situations are trite.” Then she revealed: “We write all our radio scripts”.’ (4)

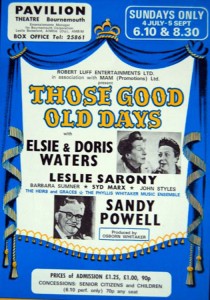

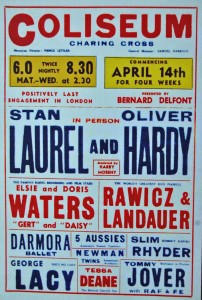

ELSIE and Doris weathered the setback and carried on with their stage work in Old Time Music Hall shows and the like. They would go on, chat a bit as themselves, sing a couple of songs, and then – to a tremendous cheer from the audience – reach into their bag of props for the hats and bits and pieces that would transform them into Gert and Daisy.

Elsie: “It really is very heartwarming. And taxi drivers nearly always recognise us and crack a joke, and when the trip’s over, they sometimes don’t want to take our money. We say: ‘Oh, come on, you must take this. Have a drink on us.’ And they say: ‘No, you’ve given me a good few laughs. Can’t take any money off you.’ And away they go. That kind of thing repays the hard work but, you know, in our job nothing’s hard work if you take the objective view. I mean, hard work means really fighting, but for us it’s a pleasure to go on and do it. There may be hard work attached to the thing, preparation and so on, but when you actually go on and do it, that’s not hard work. That’s a pleasure, if you’re really pleasing people.

“We can often translate a happening in our own lives to Gert and Daisy. For instance, when the war was over we gave a cocktail party and it was a real smasher! We went to Fortnum’s and told them we wanted eats and drinks for fifty people. So all this stuff came down by train, caviar and the lot, and the cars of the guests lined the lane with their lights on and somebody said it was like Derby Day. So we decided that Gert and Daisy must give a cocktail party. Daisy said: ‘Well, we’ve got a bit of bay rum – Bert does his hair with it – and there’s half a bottle of Guinness left over from Christmas, and a bit of ginger wine’.”

Doris: “So we shook all this rubbish up and Gert said ‘How does it taste?’ and I said ‘Awful! ’Orrible!’ and Bert said ‘These are very small glasses. You don’t know whether to drink the stuff or do your eyes with it.’ We didn’t invite Old Mother Butler. But she saw all the bikes lined up outside with their lights on.”

Elsie: “We haven’t done a lot of television. We get offers, but they want us to do things that aren’t Gert and Daisy, and we think that people don’t want to see us do things that aren’t Gert and Daisy. We want to do the thing that we can do best. About three or four years ago Ned Sherrin wanted us to do a thing down in Brighton and he wanted us to appear as Lizzie and somebody else, but it’s just not the same. He wanted us to do Gert and Daisy and call it something else. So we wouldn’t do it.”

Doris: “We don’t have to do anything we don’t want to, thank God. We would love to play The Merry Wives of Windsor, though. We did it on the air once, during the war, but we’d love to do it on the stage. After all, they were tradesmen’s wives, weren’t they? Only a cut above Gert and Daisy.”

Elsie and Doris Waters were obviously quite well off, and played a big part in the social life of Steyning. “Sometimes we slip into Gert and Daisy when we are out,” said Elsie. “People seem to like it.”

Doris: “But some people think we really are like Gert and Daisy. We’re not. We wear very nice clothes. Old Normie Hartnell has made our evening dresses for twenty-nine years.”

PAMELA Lorraine stayed with her aunts when they had an earlier house at Steyning with a larger garden, and she shared her memories with me of holidays with Elsie and Doris Waters after the war: “They were great aunts to have, and they were also godmothers to me and my brother. Our father died when we were four and three years old. We used to go to recordings of various comedy programmes they made at a BBC studio in Regent Street, I think. We also used to see them in pantomime when they played the Ugly Sisters.

“As my mother worked as a district nurse, we often spent part of holidays with them. We usually fell in the pond each holiday and had the run of their big garden, climbing trees, helping the gardener and generally having fun.

“They loved their garden and did do some weeding but most of the work was done by Bob, their gardener. They used to send hampers of garden produce to my mother to ensure we were fed properly. Very caring. They were also very strict. We weren’t allowed to come to meals without having changed first. I wasn’t allowed to wear trousers at the meal table. The cook, cleaner and gardener called me Miss Pamela and my brother Master Bernard. Definitely a bygone era!

“I remember going to fetes that they opened. They usually did a bit of Gert and Daisy. At home they were always telling funny stories. At bathtime they would do practical jokes, dress up, do little playlets etc. I remember one time it included spraying us with a soda siphon!

“They used to take us to the beach; they had a hut at Lancing on the pebbly beach. The water usually cold but there was tea to be made to warm you up afterwards. One time we went to Eastbourne and spent time on the beach there. Aunty Nan decided to show me how she used to vault over gates. She did it over the groyne we were sitting next to and landed on a surprised family the other side as she hadn’t checked it was clear!”

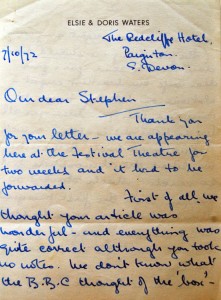

When I took my leave of Elsie and Doris Waters at the end of that first visit to Steyning, they asked me to keep in touch and, of course, I thought they were just being polite. But after my piece on them appeared in The Guardian they wrote to me: ‘It was one of the best articles we have had written about us. You are going to be a great success and we are always supposed to bring everybody luck!’

A warm correspondence followed for several years, and the sisters always seemed gratifyingly interested in my comparatively mundane doings. They sent me funny little gifts, and cuttings they thought I might find amusing, and were characteristically honest about what was happening in their lives. They were ignored by the BBC when the corporation’s 50th anniversary celebrations were being planned, and wrote: ‘We don’t know why the BBC didn’t ask us to do anything for the 50th anniversary, and when Jack said he was going to tell them about it, we said he was not to do anything of the kind.

‘We think they are treating our broadcasting efforts with the contempt they deserve, so we’ll leave it at that – except they telephoned yesterday and asked us to do a Desert Island Discs programme. We said ‘But we’ve already done one’. They said yes, but it was some time ago and these are coming over on December 23rd and Christmas Day, so perhaps it’s not so unfortunate after all!’

MY second and last meeting with the sisters two years later, also at Steyning, was sadder. Doris had obviously suffered some kind of debilitating illness – a stroke perhaps – and, though nothing was said, Elsie was covering up bravely and finishing her sentences for her when she seemed stuck for words. Big sister was sorting the little ’un out once more, as she had done all their lives.

They were still playful as ever, though – “Not today, thank you. We’ll call the police if you don’t go away,” Elsie said when Guardian photographer Don McPhee and I came to the door. “Come in, Stephen, how lovely to see you again. And this must be Don.”

We chatted for a couple of hours, and then these two elegant, expensively dressed women got out their props to transform themselves into Gert and Daisy at the kitchen table for Don to take his pictures.

Our correspondence carried on for a while longer and then, for one reason or another, it petered out as they, and I, got on with life. The invitation to visit them at Steyning was always open, though, and I regret never having taken it up again. A letter from them in 1975 ended: ‘Don’t forget where we are if you feel like a smoked haddock!

‘Much love, as ever,

Elsie and Doris.’

Ta-ta, Gert and Daisy . . .

DORIS Waters died aged 74 on August 17th, 1978, after a long illness. I wrote a formal letter of  condolence to Elsie telling her how sorry I was, and said she needn’t reply. She did, though – three handwritten pages pouring out how much her dear sister and partner had meant to her. ‘We never had a cross word,’ she wrote. ‘Doris was a marvellous person. If there were more people like her, the world would be a better place.’ Elsie lived on until June 14th, 1990, dying at the grand age of 97. Her last years were spent quietly, though she was very occasionally tempted into television studios to talk about the old days of radio and variety. In 1986 she accepted the Burma Star on behalf of her late sister as well as herself, though the honour was officially awarded to ‘Gert and Daisy.’

condolence to Elsie telling her how sorry I was, and said she needn’t reply. She did, though – three handwritten pages pouring out how much her dear sister and partner had meant to her. ‘We never had a cross word,’ she wrote. ‘Doris was a marvellous person. If there were more people like her, the world would be a better place.’ Elsie lived on until June 14th, 1990, dying at the grand age of 97. Her last years were spent quietly, though she was very occasionally tempted into television studios to talk about the old days of radio and variety. In 1986 she accepted the Burma Star on behalf of her late sister as well as herself, though the honour was officially awarded to ‘Gert and Daisy.’

The sisters say goodnight in another clip from Gert and Daisy’s Weekend.

All text Copyright Stephen Dixon 2013. A much shorter version of this story appeared in The Guardian newspaper in 1972. All illustrations, except where specified, from Stephen Dixon Collection, acquired from various sources over a 40-year period and in many cases provided by the artists themselves. If anyone has copyright or permission issues, please contact me.

Other sources:

(1) Song and Sketch Transcripts of the British Music Hall Performers Elsie and Doris Waters, by Paul Matthew St Pierre (Studies in Song and Dance, Vol 1, The Edwin Mellon Press, 2003).

(2) This ‘shared lover’ story was told to me by Leslie Sarony among several others. It is also mentioned in Grace, Beauty and Banjos, by Michael Kilgarriff (Oberon Books, 1998).

(3) Daily Mail, August 11, 1959.

(4) Daily Herald, August 24, 1959.

stephendee

| #

Doesn’t ring a bell with me, Stefan, tho it’s a very typical Sarony line. Anyone? Stephen

stefan Beard

| #

Just been reading the Leslie Sarony piece. Absolutely fantastic. Well done. A question if you don’t mind. Does anyone know the the title of the Leslie Sarony song that has the line “Oi ! how you gettin’ on? ” in it ?

ruskimic

| #

I do hope you can help me. I have been searching for many years for my Great Uncle Mr Albert Edward Rayner who went under the name of Dan Rayner. I believe he worked the Music Halls but I do know for sure he worked with Fred Karno. When Charlie Chaplin left Fred in America over a Pay dispute the American backers of the tour insisted that my Great Uncle Dan Rayner be called over from England to take Charlie Chaplin’s Place. It appears Dan was liked more at that time in America than Charlie was. Another man in the troupe at that time was Stan Laurel. When the show folded Dan was asked along with Stan to stay in America. As we know Stan stayed and found he fame and fortune. Dan however chose to return to England. He was last that I can find in a play Dick Wittington at the Empire Theatre advertised in the a local paper in Durham in 1948. Unfortunately I have not been able to find when or where he died. I am hoping that maybe on your search you came across some info on Dan Rayner. I live in Australia so am unable to search all the death records for England with out it costing me a fortune. So any help you maybe able to give me would be really appreciated. I know he went to America twice and once to Australia and also once to South Africa. I do know he was married to a lady named Barbara Robinson and they had a son Conrad Paul Rayner but I have been unable to find any thing out about these two members of his family. I do know they separated before 1935 and he lived with another lady named Phyliss but as to her last name I have no idea. I have been searching for nearly 10 yrs now and I don’t think there is any thing left on the net that can help me. You it would appear maybe my last chance. I will keep my fingers crossed that you did come across some info on him or you know some one that maybe able to help. He went to America in 1913 on the Lusitania and it shows at this time he is married. He then returns to America in 1914 on the ship Adriatic. I do believe he also did a radio show after 1935 for quite some time but do not know the name of that show. I do hope you can help in my search for my Great Uncle.

I also might add my great grandfather was Edwin Richard Barwick. He was also a Music Hall performer and appeared in the first Royal Command Performance. If you get the picture and Index to that even you will see him standing next to Pavlova. I would love to hear any information you may have found out about him. I do believe he was one of the first members of the charity named water rats, I know star was spelt back wards to get the rats part. Edwin did a lot of work for this charity in his day. What I would love to know is if there is any recording of Edwin Performing and if so how I would go about getting a copy or seeing any recording. I do have a photo copy of an old theatre bill with my grandfathers name boldly written on it. Again any help would be appreciated.

All the best and I look forward to hearing back from you in the near future

Kim Rayner

my email address is ruskimic@yahoo.com.au