Chesney Allen

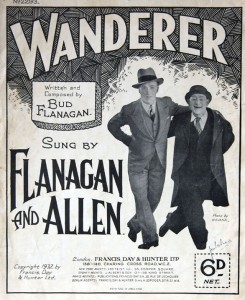

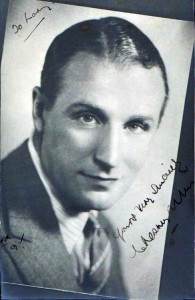

CHESNEY Allen had got himself into a bit of a state. The survivor of variety’s greatest double-act had agreed to see me even though for 20 years he had been turning down such requests. Then he had second thoughts and proposed that the interview be conducted through a combination of questions submitted by post and follow-up telephone conversations.

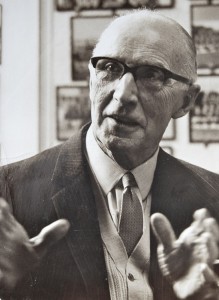

After a flurry of increasingly confusing calls and letters it became obvious that this wasn’t working too well, so he finally said he would meet me at an office he used on London’s Oxford Street, opposite Selfridge’s. Ches was visibly disconcerted by my youthfulness when I arrived and became quite agitated a few minutes later when The Guardian’s photographer, E. Hamilton West (known to all as Ted), turned up and started pointing a camera at him.

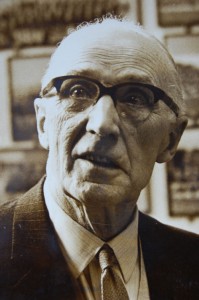

He was a tall, stooped, dignified man, still imposing and attractive at 78, courteous and charming in spite of his nervousness with me and displeasure at the presence of Ted – I thought he had understood that a photographer had been organised – and he had something about him that suggested a retired solicitor, the occupation for which he had once been destined.

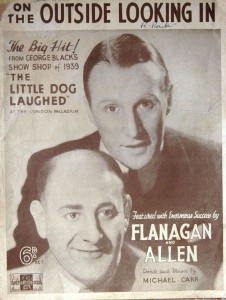

But the story he had to tell had nothing of the dryness of law; it was about a remarkable and wonderful friendship born in the horrors of the First World War trenches and forged ten years later in the hurly-burly of music hall into an act that reached the very pinnacle of show business as Flanagan and Allen produced hit after hit record, sold out theatres all over Britain and, with other members of the legendary Crazy Gang, starred in 16 films through the 1930s and 40s.

Go into any large music store today, or check online, and you will find Flanagan and Allen; switch on the television and you will hear those lilting voices singing Run Rabbit Run or one of the other hits behind an ad somewhere, or Bud asking Who Do You Think You Are Kidding Mr Hitler? over the titles in a re-run of Dad’s Army. The two unlikely but dear pals may be long gone, but Flanagan and Allen live on, true immortals of the music halls, and Ches put his finger on the simple reason. “I think we were a part of the people,” he told me. “There was no barrier.”

Here’s a clip of them singing Round the Back of the Arches, from a 1942 Listen to Britain feature.

A PART of the people. These two men from wildly-contrasting backgrounds had a relationship that was unique among double-acts on the British halls. It was far from the traditional bullying, supercilious straight man and buffoonish comic; audiences sensed that Bud and Ches had become social equals through shared hardship. As one writer put it: ‘Seldom absent from their songs was a concern for the underdog of society, for the gutterspun philosophy that equated poverty with riches. One knew instinctively as they sang that the attitude to life embodied in their songs had itself been conditioned by their own experiences in leaner times, that there had been occasions when the rain had entered their shoes, when their dreams and schemes had fallen on stony ground.’ (1)

Often played out against a backdrop of The Embankment, their act was built around two men, down on their luck, chancing across each other and sharing jokey banter and a song or two before seeking shelter wherever they could find it; nights spent on cobblestones in all weathers, waiting for dawn and the hope a new day might bring. It always finished the same way. Haunted by a single spotlight, they slowly strolled the length of the stage, swaying slightly to the music: Bud in voluminous raccoon coat and battered straw hat, his high, lamenting cantor’s wail soaring to the back of the gallery, and Ches behind, hand on Bud’s shoulder, shabby-dapper and deadpan, emphasising the words in a mellow half-spoken croak a split-second behind the beat . . .

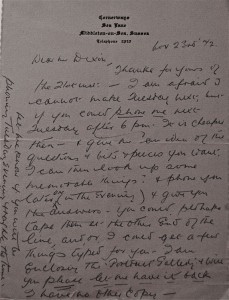

Pavement is our pillow, No matter where we stray. Underneath the arches We’ll dream our dreams away.’A week or so after our meeting, I received a letter from Ches that brought into focus the prickliness of an old-timer no longer in the limelight, the poignant and understandable vanity of a once-handsome man who preferred audiences to remember him as he had been in 1946, when he retired from performing, the gulf of years between us, and an assumption about my domestic circumstances (I lived in a small furnished flat on the outskirts of Manchester) that made me smile.

Accompanying the letter was a gift, a newly-issued LP of Flanagan and Allen’s greatest hits. ‘You may like it,’ he wrote diffidently. ‘In any case, you maybe have an elderly daily help, and she might like it. I have received the photographs from Mr Hamilton West. They are remarkably like me I’m very sorry to say! However, I suppose one must accept these lines on the face (more than there are at Clapham Junction!) when one is over 40.’ He ended with a more upbeat postscript: ‘Did you hear the two characters on Coronation Street singing Underneath the Arches last night?’

WILLIAM Ernest Chesney Allen was born into the solid middle-classes in Brighton, Sussex, in 1893, the son of a well-to-do builder. He began training for a career in law at a barristers’ office near the Law Courts on The Strand but in 1910 threw it all up to go on stage as an actor in stock when he was still a teenager, touring in melodramas and popular fare of the East Lynne variety. Through playing a wide variety of parts, he began to acquire the timing skills that would one day make him variety’s greatest straight man.

“Timing is not difficult if you have the basic theatre training. In my case I had a short spell when I was 16 at a stage school in Clapham Road, London, then I went on the legit stage playing in stock – rep, it’s called nowadays. Six plays a week. Dramas, playing heavies or juveniles for a couple of years, and then farce and music hall. If you’re doing drama you’re improving your timing all the time, and this training helped me to get the laughs when I went into comedy. You have to have perfect timing to get the best out of a gag.”

That was all Ches would say on the subject of timing. But to be a top straight man you needed prodigious skills. Another star who began his career on the British halls as a straight man, Cary Grant, once commented: “The straight man in a double act is the conductor of the act, responsible for the tempo and the success of the performance. The comic has to say his lines funnily; the straight man has to know when to cut into a laugh, when to let a laugh ride, the exact point at which the laugh starts to fade so he can feed the comic another line. He drives the act, timing it, alert to any small change in audience response.”

In 1915 Ches enlisted in the 9th Lancers, was sent overseas and rode as a cavalry soldier. He was part of the mounted escort to the 14th Army Corps Commander, General Lieutenant The Earl of Cavan, KP, and on more than one occasion was escort to the Prince of Wales. “I don’t care what they say about the Prince of Wales – he was a very brave man,” said Ches. “They had to stop him going to the Front Line eventually. Any man with two stripes on his arm was given orders to prevent him going to the Front Line at all costs, because he was too valuable to lose.”

When the cavalry was transformed into infantry, he saw service in Bapaume as a Sergeant in the 10th Battalion Royal West Kents and was twice gassed. After going to Italy, the West Kents returned to France for a German offensive during which they were so badly cut up that only about 50 men were left to answer roll call. He went back to Britain to recuperate and then returned with his Battalion to France.

It was in a Flanders café in 1917 that he started chatting to another weary and begrimed soldier and found that they had the stage in common. Chiam Reuben Weintrop was then calling himself Robert Winthrop and he was to become Bud Wayne and Chick Harlem before settling on his final stage name. “You’re a bastard,” he had told an antisemitic Sergeant Flanagan, “and one day I’m going to make your name the laughing stock of England.”

Bud fleshed out the historic meeting a little in his autobiography: ‘The village, or what was left of it, was Poperinghe, which boasted a couple of frowsty estaminets. I wandered into one of them for egg and chips. The place was crowded, but one table for four had only three at it, so I sat down, gave my order, and started a conversation with a spruce-looking soldier. He was in the Royal West Kents and had been a legitimate actor in peacetime. His name was Chesney Allen. I told him I was a comedian, and after a few beers we said goodnight. He went his way, and I went mine.’ (2)

BUD’S youth had been a good deal more chaotic than that of Ches. He was one of ten children born in Whitechapel in 1896 to Wolf and Yetta Weintrop, Polish Jews who had fled to London to escape persecution. By the age of ten he was working as a call-boy at the Cambridge Music Hall and in 1908 made his stage debut as a conjuror in a talent contest at the London Music Hall, billed as ‘Fargo the Boy Wizard.’

When he was 14 he walked to Southampton and, claiming to be a 17-year-old electrician, blagged his way on to the SS Majestic and jumped ship when the liner reached New York. The teenager had many adventures in the States, including selling newspapers, touring with a vaudeville troupe, farm labouring, boxing (as ‘Canvasback Cohen’) and being thrown in jail for vagrancy. He later claimed he sang in a brothel for the price of a cup of coffee, but it should be noted that a number of sources mention Bud’s propensity for embellishing the truth.

He returned to England in 1915 to enlist in the Royal Field Artillery and was sent to France. In March 1918 he was with a gun team when two German shells went off nearby. Wounded and temporarily blinded by gas, he was taken to hospital in Deauville and demobbed in February 1919. ‘War turned him into the kind of tragic-comic hero who found humour in adversity and solace in the company of the lowly, the poor and the scared,’ wrote Maureen Owen, the Crazy Gang’s biographer. (3)

After the war Ches went back into the theatre. He was still a straight actor, but even before he joined up he had acquired a taste for music hall, playing in three-handed dramatic sketches sandwiched between comics and jugglers on various bills, and in that atmosphere the germ of an idea for a double-act began to grow. Allen and company were once barnstorming at the Willesden Empire in a sentimental sketch called Dear Old Charlie, and it was their unenviable task to follow a skilled and volatile comedy star, Billy Williams, ‘The Man in the White Velvet Suit.’ An Australian, Williams popularised chorus songs such as Tickle Me Timothy, The Kangaroo Hop and When Father Papered the Parlour.

“Well, it was impossible to follow this man! He used to milk the audience – looking up at the gallery, looking at his watch, then doing a bit more. That kept them all going. Anyway, we followed with our sketch as best we could. Now we had on the bill a pair or comics called Fine and Hurley. Johnny Hurley was a relative of Alec Hurley, who was one of Marie Lloyd’s husbands, and Fine and Hurley were a front-cloth double-act. Fine asked me what I was getting paid and I told him £2 a week. He said: ‘You want to do a double act like Johnny and me. We’re getting £20 a week here.’

Here’s Billy Williams with When Father Papered the Parlour.

“That was fabulous money to me. It stuck in my mind, and when I got out of the services I was working as an actor in the West End – although I was never a West End type of actor really! I had a very small but showy part in an American light comedy at the Globe called Ready Money. I used to come on every so often and say: ‘I’m looking for a little girl. She comes out here and she goes in there.’ I was a fop, and I had to wear a monocle. That part made me realise I liked working in comedy. But I had to carry on as a straight actor for a while because the comedian I wanted to team up with, Stan Stanford, was in the Army in Ireland and couldn’t get out. So I went on playing in dramas until Stanford got out, and then we teamed up. We weren’t very successful, I suppose, but we got a living.”

Early in 1920 Stanford and Allen joined Flo and Co, the touring company of the great singalong star Florrie Forde, who had many magnificent songs associated with her name, among them Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag, It’s A Long Way to Tipperary and Down at the Old Bull and Bush.

Florrie Forde

“Then, in Mansfield one day, I happened to meet Bud again, and he stuck in my mind afterwards. He was in blackface, doing an act called Harlem and Bronx with a girl. Stanford and I were on the same bill. Stan wanted to leave the act when we were with Florrie Forde, but Florrie said she wanted me to stay on. I always liked the business side of entertainment, and I started to handle Florrie’s business and became her manager, and eventually I was producing the whole bag of tricks and booking the artists and so forth.

“I was with Florrie Forde for many years – nine or ten. I met my wife, Aleta Turner, in one of Miss Forde’s pantomimes. She was the Principal Girl. I really think Florrie Forde married us – she arranged everything, bought a house in Streatham for which we paid a ridiculously small rent. I cannot thank her enough for her many kindnesses. She was a wonderful, wonderful woman, very generous and particularly kind to the smaller people – chorus, wardrobe and stage staff. Aleta and I have been married for 48 years now, a little unusual in our profession.

“And one time in 1924 when we playing Glasgow with a Scots comedian called Wullie Lindsay – he was wonderful in Glasgow and Edinburgh, but when he came South nobody could understand a word he was saying – I found that Bud was playing at Kilmarnock. His name was Bud Wayne then, I think. So a meeting was arranged and we teamed up as Flanagan and Allen from then on.”

Florrie Forde had been the prime mover in getting them together. She saw something in the emotional, undisciplined, insubordinate, clownish Bud that would perfectly fit with the meticulous, impassive, detail-obsessed Ches. She groomed Bud during the years he was with Flo and Co, correcting his poor timing and drumming into him the virtues of self-control. He had been all over the place, exploding on stage like a firework, forcing himself on audiences and alienating them by trying too hard. She pointed to Ches as a model of relaxed self-confidence. It seems likely that Forde also gave him his stage name, whatever Bud claimed he had told that unpleasant sergeant during the war; Flanagan was her maiden name and also the title of one of her biggest song hits.

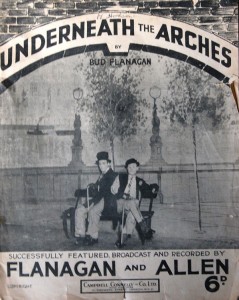

THEN the economic slump hit Britain, and by 1931 Florrie Forde found that touring big shows was no longer viable. Ches and Bud decided to try the variety circuit on their own and arranged a trial run at the Argyle Theatre, Birkenhead. They walked the streets together discussing ideas, remembering gags and routines that could be reworked and structuring the act. Both agreed that a song Bud had written a few years earlier, Underneath the Arches, would be a perfect finish.

Their debut was received a lot of favourable attention and on foot of it Val Parnell of Moss Empires wired to offer Flanagan and Allen a double contract at the Palladium and the Holborn Empire in London. Their opening eight-minute spot at Holborn overran by 16 minutes and left the audience yelling for more. “When our first big success came, we had the world at our feet,” Ches said almost apologetically. “Forgive me for saying this, but I have to tell the truth. I was the businessman of the act, and after our first week at the Holborn Empire we had films offered us, Ziegfield contacted us from New York, an Australian tour was offered. We had everything.”

Listening to the old records, their cross-talk style doesn’t sound too funny now, but it was evidently refreshingly different at the time. It involved quickfire back and forth interplay based around an immigrant’s malapropisms and misunderstanding of the language, but there was a slyness to Bud’s delivery that suggested he might be playing the knowing fool and secretly mocking his dignified interlocutor. When Bud arrived at the correct word he would shout “Oi!” echoed by the band.

THE act always featured a number of songs – nostalgic or patriotic or, more likely, evoking hard times and the camaraderie of ordinary people bonding against misfortune. And they invariably ended with that song, which had been growing slowly in popularity.

“Underneath the Arches was written by Bud, words and music, in some digs in 1928,” said Ches, “and we sang it for two or three years before it really caught on. In those days, you see, a lot of people really did have to sleep under the arches and I think the song was written partly with them in mind. Bud had roughed it a lot earlier. He’d been a taxi driver and he’d been to America and roughed it there. He once walked from London to Glasgow. So he did know something about ‘the arches.’ Then, in 1934, the song became the best-seller in this country. Later on it was a tremendous seller in America after the war, too, because American soldiers used to come over here and they got to know the song.”

Their relationship was quite complicated. There was quite obviously a tremendous and genuine affection – a love, even – between these men. “Bud was Jewish, I’m Christian and it was a wonderful combination,” said Ches, misty-eyed behind his glasses.

Their relationship was quite complicated. There was quite obviously a tremendous and genuine affection – a love, even – between these men. “Bud was Jewish, I’m Christian and it was a wonderful combination,” said Ches, misty-eyed behind his glasses.

“Our personalities complemented each other perfectly. And he really was one of the loveliest men you could ever hope to meet. Money meant absolutely nothing to him. He never worried about money at all. We loved golf and we were once appearing at the Pavilion, Glasgow. We were having a round of golf in the middle of the week and Bud said to me: ‘Here, Ches, how much are we getting here?’ I told him and he said: ‘Are we? Oh well, I can buy another club then.’ And that was when we were right at the very top. He loved life and he spent a lot of money and he lived well. He was a wonderful man and it was a wonderful partnership. Bud and I, with our wives, were friends offstage, of course, but we didn’t meet too often socially because that might spoil the business arrangement. But we were very, very friendly.”

They bonded through, among other things, an intense patriotism. Bud had rushed home from America in 1915 to join up and fight for the country that had provided sanctuary for his parents and siblings, and in the same war Ches had been entrusted with guarding the life of a future King. Then there was their love of racing – during the thin time just before their breakthrough success at the Argyle they had considered quitting and going into business together as bookmakers.

They may not have socialised constantly but when Flanagan’s only son, Buddy, died of leukemia and was cremated in the States in 1955, it was Ches, accompanied by another close friend, bandleader Jack Hylton, who met Bud off the plane at London Airport. He was always there for his pal when it mattered.

He may have found Bud to be “one of the loveliest men you could ever hope to meet,” but his opinion was not generally shared in show business. Bud was said to be extremely difficult to work with, moody, demanding and boastful, with an insecurity-driven tendency to always get the upper hand, to demonstrate that he was better than the next man.

WHEN Flanagan and Allen were with the Crazy Gang, the diplomatic and self-effacing Ches often had to step in to soothe ruffled feathers when Bud had antagonised one or other of the usually easygoing and mischievous troupe. Ches was defender, protector and apologist as well as friend. The cynical might suspect that Ches, ever the astute businessman and canny gambler, was just guarding his investment, but there seems much more to it than that.

It was as if Ches felt a strong personal responsibility towards his aggressive and volatile partner and saw him as an emotionally vulnerable friend, and that he also assumed professional guardianship over the wild, sprawling comic invention of Bud Flanagan that he was able to control and mould into a viable act.

It was in 1932 that Flanagan and Allen joined the anarchic Crazy Gang. I asked Ches how it came about. “Well, it was started by Nervo and Knox in the first place. They started a thing called The Young Bloods of Variety and they brought in these things that had never been done before, like interruptions from the boxes, and the artists walking down the auditorium. Really crazy things. They did it at the London Palladium and had a very successful two weeks there. Then George Black the impresario decided that he’d like to have a Crazy Month in 1932, and that’s when we joined the show. There was Nervo and Knox, Naughton and Gold, Flanagan and Allen and Caryll and Mundy, and it was a huge success. The month ran to six weeks, then eight weeks and eventually we ran for eight months – twice nightly, two matinees, 14 shows a week.

“We probably played to more people than The Mousetrap has played to in 20 years, and when the Gang went off after eight months Bud and I stayed on. We did summer shows with Jack Hylton and Harry Roy. They used to last eight to ten weeks then we’d have a couple of weeks’ holiday then go into another Crazy Gang show. We made sixteen films, which we enjoyed because we were doing something different every day.”

The films, from The Bailiffs in 1932 to Here Comes the Sun in 1945, though ramshackle, stand up reasonably well after all these years. The Gang was a bunch of funny little men – pencil-moustached Teddy Knox, bald baby Charlie Naughton and pixie-faced Jimmies Nervo and Gold – and it is interesting to note that Ches, though more laconic than the others, rarely distanced himself as straight man to the ensemble but joined in the chaos and slapstick with just as much gusto as his colleagues. However, because he was taller and better-looking, and had a more authoritative voice, he tended to take the lead when something needed to be explained or planned.

A scene from Okay for Sound (1937) typifies the Gang’s popular image. They are buskers during the hard times, trying to entertain a theatre queue with a motley collection of makeshift musical instruments. There are a few deft sight gags from Naughton and Gold, and some verbal interplay between Nervo – known as ‘Cecil’ to his partner – and Knox, who always affected a speech impediment: “You don’t ’alf shay shome shilly things, Sheshil.”

If the others in the Gang seem to be unemployed working men, or down-on-their-luck theatricals, Ches is obviously from a slightly higher social echelon, and more dapper in spite of his curling collar and worn cuffs, but he never places himself above his pals in any way – he is like their pet ‘toff’ but he does not patronise them, nor they him. Hardship has once again proved to be the great leveller: these men may be down, but they will never be out as long as they have each other, the price of a bun and a cup of tea and the shelter of the arches for the night. The sequence ends with Flanagan and Allen singing Free, which finds solace and value in the reduced circumstances of these ‘six tumbleweeds,’ with the rest of Gang joining in towards the end. It is still a charming and touching scene.

And here it is . . .

Films had to be carefully-structured, of course, but there was more scope for improvisation on stage. “In the Crazy Gang stage shows we used to ad-lib a good deal. We’d go on and Bud would say ‘Say something that’s not in the script, Ches,’ and I’d say something and we’d take it from there and build it up. We often made it up as we went along. We rarely said the same things two nights on the run, but I always brought Bud back from his flight of fancy in time for the songs.

“I would say that I was rather a con-man in the act, always tricking Bud and I was never presented as a fool, except at the end of the act when I would make a little speech and Bud would be taking the mickey. I would be thanking the audience and Bud would be pulling my hair and saying ‘Just a wig, you know,’ or ‘This is just makeup you know. My God, he doesn’t look a bit like this offstage!’ And the audience loved this because I was always rather well-dressed and dignified on the stage.

“Managements didn’t mind if we ran a few minutes over. We had a set routine, though, as a framework for all this. We’d push off with a racing skit. Then Bud used to do a comic Jewish speech, followed by me doing a straight monologue as a broken-down swell. While this went on Bud would be changing and then we’d open a new scene with us both on a park bench and talk about imaginary people. All very fast.

“Hello Gonnigan,’ Bud would say, and I’d look round.

‘“Where?’

“Bud would say: ‘He’s gone again.’

“We’d do a few songs and always finish up with Underneath the Arches. Audiences used to love that song. It may be corny, but I think it had a message. It wasn’t ‘I love you I love you I love you,’ like nowadays.”

Their peak as recording artists came during the Second World War when they, along with Vera Lynn, came to represent resolution, determination and stoicism in the face of the unthinkable. Some of their songs from this period are overtly patriotic, such as (We’re Gonna) Hang Out the Washing on the Siegfried Line and FDR Jones and others more subtle, like the thinly-disguised attack on Germany in Run Rabbit Run, but most involve a kind of wistful longing – Miss You, We’ll Smile Again – or the joy of reunion: There’s A Boy Coming Home on Leave.

IN 1946 Flanagan and Allen split up at the height of their fame. Ches’s health had been poor for some time; a masseur had to be standing by each night to get him in shape to go on stage. “During the Second World War we worked hard and that’s what really finished me and set off this osteo-arthritis. We went overseas, up the line, doing shows from jeeps. I had to give up my stage career with the greatest reluctance. I went to see a specialist and he told me to give up the stage. We were playing at the Prince of Wales Theatre and Bud was waiting there for me when I got back from seeing the specialist. I just looked at him and I said ‘It’s the finish Bud.’

“I went to see Jack Hylton and booked Bud into the Adelphi Theatre as Buttons in pantomime, and then I went into a nursing home. When I came out I just didn’t know what to do. You can’t just retire when you’re 51. I walked my dog around the village and by the third week I was going crazy. Now I could have done one of three things. I was very friendly with John Baxter, the film director at British National, who made all the Lucan and McShane Old Mother Riley films and also four for the Crazy Gang, and I could have gone in with him. Or I could have gone into bookmaking. Or I could have gone into management. In the end I went into an agency which had about 20 stars on its books as well as the Crazy Gang and I had another long career as an agent – 25 years.

“When I got tired of the agency side I started producing and promoting summer shows. I did two Royal Command performances after I retired and I still made the occasional stage appearance with Bud for sentiment’s sake and we made one or two records and four TV appearances, just singing the songs.”

I asked him which he preferred, appearing on stage or working behind the scenes. “In front of the footlights, of course. There’s no business like show business – corny but true. One would be a hypocrite if one did not admit, appreciate and feel happy at the adulation which success must bring. It was a wonderful time, and I’d like it to happen all over again.”

Ches handled Bud’s business affairs until the great comedian died in 1968, aged 72. One of the last things he was able to do for his old partner was negotiate on his behalf for the Dad’s Army signature tune. Bud had enjoyed a successful career as a solo act or with the rest of the Crazy Gang until they died or got too old to carry on. After the Gang’s last Royal Variety Show, Prince Philip asked Bud what he would be doing next. “Well,” he replied, “I’ve got a crate of brown ale in the dressing room. I thought we might all go back to your place.”

His former straight man lived quietly on the South Coast with Aleta – they were described to me as an elegant and rather courtly old couple – and was an avid follower of snooker and racing: “I have owned a few horses but not now. It is far too expensive. Both Bud and I always loved racing. I think we got the bug from Florrie Forde. She would ask me when booking the tours to be sure and get some Race Weeks, so we would find ourselves at Doncaster for the St Leger, York for the Ebor or September meeting and Ayr for the spring meeting etcetera.”

Because he had been retired for so long, Ches was rarely recognised when he was out and about, but if he was obliged to disclose his identity older members of the public often became quite excited, and he found himself being thanked for the pleasure he and his partner had brought to so many people for so many years; thanked, most of all, for a song that started life as a sentimental tribute to the underdog during the Depression and which became – and remains – a lasting paean to old-fashioned comradeship and loyalty.

And that is where we will leave Flanagan and Allen . . . underneath the arches, Ches’s steady hand on his dear, difficult pal’s shoulder as they stroll into history, dreaming their dreams away.

Goodbye to the arches, Ches . . .

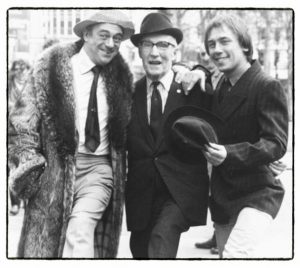

Roy Hudd, Ches and Christopher Timothy

IN spite of the ill-health that had forced him into retirement in 1946, Chesney Allen outlived the rest of the Crazy Gang, and after keeping himself out of the limelight for 25 years emerged in the late 1970s to enjoy a glorious last burst of public acclamation. He made several television chat-show appearances, and in 1981 talked about his career and sang some of the old songs in an episode of the BBC series The Old Boy Network.

The following year a musical based around Flanagan and Allen, Underneath the Arches, opened at the Chichester Festival and later transferred to London’s Prince of Wales Theatre. Roy Hudd or Bernie Winters played Bud, and Christopher Timothy or Leslie Crowther was Ches. Occasionally, as Hudd and Timothy strolled the length of the stage singing the title song, Timothy would slip into the wings, to be replaced by the real Chesney Allen. It was reported that the roar of delight from the audience when this happened nearly lifted the roof off the theatre. Variety’s greatest straight man died, aged 88, in 1982.

A last look at Ches and the rest of the Gang, again from Okay for Sound. They’re sailors this time, and their comic routine is followed by famed tenor Peter Dawson (a somewhat elderly naval rating, and gurning horribly as he sings) before the boys re-appear for the finale. Currently you can find the full-length movie, plus Alf’s Button Afloat (1938) and The Frozen Limits (1939) on YouTube.

All text Copyright Stephen Dixon 2013. A shorter version of this story appeared in The Guardian newspaper in the 1970s. All illustrations, except where specified, from Stephen Dixon Collection, acquired from various sources over a 40-year period and in many cases provided by the artists themselves in the 1970s. If anyone has copyright or permission issues, please contact me.

Other sources:

(1) Funny Way to be a Hero, By John Fisher. Frederick Muller, 1973.

(2) My Crazy Life, by Bud Flanagan. Frederick Muller, 1961.

(3) The Crazy Gang, by Maureen Owen. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986.

stephendee

| #

Doesn’t ring a bell with me, Stefan, tho it’s a very typical Sarony line. Anyone? Stephen

stefan Beard

| #

Just been reading the Leslie Sarony piece. Absolutely fantastic. Well done. A question if you don’t mind. Does anyone know the the title of the Leslie Sarony song that has the line “Oi ! how you gettin’ on? ” in it ?

ruskimic

| #

I do hope you can help me. I have been searching for many years for my Great Uncle Mr Albert Edward Rayner who went under the name of Dan Rayner. I believe he worked the Music Halls but I do know for sure he worked with Fred Karno. When Charlie Chaplin left Fred in America over a Pay dispute the American backers of the tour insisted that my Great Uncle Dan Rayner be called over from England to take Charlie Chaplin’s Place. It appears Dan was liked more at that time in America than Charlie was. Another man in the troupe at that time was Stan Laurel. When the show folded Dan was asked along with Stan to stay in America. As we know Stan stayed and found he fame and fortune. Dan however chose to return to England. He was last that I can find in a play Dick Wittington at the Empire Theatre advertised in the a local paper in Durham in 1948. Unfortunately I have not been able to find when or where he died. I am hoping that maybe on your search you came across some info on Dan Rayner. I live in Australia so am unable to search all the death records for England with out it costing me a fortune. So any help you maybe able to give me would be really appreciated. I know he went to America twice and once to Australia and also once to South Africa. I do know he was married to a lady named Barbara Robinson and they had a son Conrad Paul Rayner but I have been unable to find any thing out about these two members of his family. I do know they separated before 1935 and he lived with another lady named Phyliss but as to her last name I have no idea. I have been searching for nearly 10 yrs now and I don’t think there is any thing left on the net that can help me. You it would appear maybe my last chance. I will keep my fingers crossed that you did come across some info on him or you know some one that maybe able to help. He went to America in 1913 on the Lusitania and it shows at this time he is married. He then returns to America in 1914 on the ship Adriatic. I do believe he also did a radio show after 1935 for quite some time but do not know the name of that show. I do hope you can help in my search for my Great Uncle.

I also might add my great grandfather was Edwin Richard Barwick. He was also a Music Hall performer and appeared in the first Royal Command Performance. If you get the picture and Index to that even you will see him standing next to Pavlova. I would love to hear any information you may have found out about him. I do believe he was one of the first members of the charity named water rats, I know star was spelt back wards to get the rats part. Edwin did a lot of work for this charity in his day. What I would love to know is if there is any recording of Edwin Performing and if so how I would go about getting a copy or seeing any recording. I do have a photo copy of an old theatre bill with my grandfathers name boldly written on it. Again any help would be appreciated.

All the best and I look forward to hearing back from you in the near future

Kim Rayner

my email address is ruskimic@yahoo.com.au